Take off your jacket: The erotics of books

Past the talking stage is the reading stage. Ed Luker looks between the lines to find out what makes sharing words with new and old lovers so titillating.

Scan to download

The all-too-real practice of “ghosting” has become its own urban legend—everyone and their friend has a story about being or experiencing a ghost. Sophie Mackintosh considers communing with and communicating about a modern-day dating phenomenon.

Much like a person ghosted tries to understand what has happened, “ghosting” is a word frequently in search of a definition. Most commonly defined as the act of having someone cut off all contact, without explanation, at some point during a relationship, ghosting appears to be a permanent addition to the terminology defining our recent dating landscape—a concept we are expected to grapple with, trying to understand it, place it, and maybe justify it. It’s a term that’s been absorbed into our collective lexicon; no casual discussion of dating among friends seems to be complete without it, with even the Washington Post outraged at the idea that "Ghosting is normal now. That’s completely bonkers,” guides to “micro-ghosting,” and even advice on what to do if you get ghosted at work.

The slipperiness of it has taken hold of our collective fascination. It seems like bad manners—cruel, even. An act so outrageously rude that you wouldn't expect anyone to do it to you, or stand by someone ghosting a friend. And yet it's very likely that you have been ghosted, or have ghosted in turn.

This cognitive dissonance—the gap between our beliefs and our behaviors, what we believe in and how we actually act—is at least part of this fascination. How can it be that those who are normally kind and considerate are able to simply cut contact? We know, or can imagine, how it feels to be ghosted. Perhaps less acknowledged is our turn as a ghost. What does that mean for our own sense of self, and for the people we believe ourselves to be?

I have collected enough anecdotes about relationship disappearances to know that ghosting has probably been around as long as humans have been forming romantic connections, including a particularly heart-wrenching story about an elderly neighbor whose beau absconded without warning after she lost all her teeth in a botched dental procedure. What is new is its positioning and pathologizing. We've created a whole new language around it, with attendant terms such as “breadcrumbing” (ghosting but occasionally dropping a tiny bit of contact, a “breadcrumb” if you will), “Marleying” (ghosting but popping up in the festive season), “orbiting” (ghosting but continuing to drop likes and views on social media activity.)

With this language comes a diagnosis, a media positioning that takes this practice as a sign of emotional immaturity, but there is also increasingly a reading of it as an act of cut-throat self-care. Such a perspective raises an uncomfortable question: how much do we owe people, and how much are we owed in return? What happens if our answers tend, increasingly, towards “nothing”? In a world where individual comfort is increasingly prioritized, where even a minor feeling of conflict can feel abrasive, ghosting can happen more and more—platonically and romantically. There have never been more ways to slip away. We might feel that if a situation doesn't serve us, even if it doesn't fall neatly into the bracket of “toxic” but into some sort of gray area that you can justify as adjacent (or maybe you're just bored, or a hundred other reasons), why not leave? It can be as easy as the click of a block button, the sorting of a chat into the “archive” section, and it's done. Is that the self-care of setting a boundary—or is it a lazy act of conflict avoidance, at best, or cruelty, at worst?

Both positions, though, seemed propped on conflicting moral high ground—one based on the idea that ghosters are damaged and damaging, unable to have the conversations necessary to cut something off gracefully, and the other prizing individual autonomy and comfort. Add in increasing burnout, cynicism, and choice fatigue when it comes to modern dating, and no wonder we're so confused.

A compassionate outlook requires us to wonder if it’s true that ghosts are terrible people with no capacity for big conversations? After one or two dates, the act of sending a well-composed slightly-less-than-breakup text can feel earnest and humiliating. In a fast-paced world, a fizzling-out can feel kinder than listing the reasons for why someone doesn't want to see you again. There can be a sort of grace in disappearing, rather than to continue with something you know doesn't have a future.

We’re fascinated by ghosting, too, because it speaks to both the seductive urge to abandon yourself to an impulse, and an integral fear within ourselves about what it feels like to actually be abandoned. In a world of obligations, the sheer adrenaline relief of simply walking out, unaccountable and gloriously free, can feel seductive.

But rejection works on the same pathways in the brain as physical pain. The counterpoint to the relief of avoiding a tricky conversation is that the ghosted party does not receive the much-vaunted “closure,” and instead our minds often seek to fill in the gaps instead, to go over and over what they may have done wrong. That idea that there is something we have done that has prompted the ghosting, something within ourselves, can feel much more insidious and upsetting than a cursory break-up text. It's the ambiguity within the act, rather than the act itself, that wounds us—and which keeps us, culturally, trying to understand ghosting as a behavior, how to avoid it and recover from it, even as we may find ourselves doing it, against all rational knowledge of why we shouldn’t.

Perhaps it’s a collective entitlement (or delusion) about how easy we feel our relationships should be, how effortless we want them to be, and by extension how we feel our existence in the world should be. To abandon a relationship rather than working on one in which we have revealed even the most minor flaws, to chase after the next thing which is currently perfect in its newness and promise, can feel not just easier but more exciting. To throw up our hands and just admit that it's easier to temporarily feel like a bad person than to invest time and energy into the feelings of someone you'll likely never see again, someone who still might just be a virtual avatar on a screen, can feel easier too. But there’s no doubt that the act of ghosting, and our continuous circling around it, reveals something not just about the state of dating, but about our changing relationships to entitlement, selflessness, and emotional fatigue too.

There is something destabilizing and dehumanizing to the idea that with just a few taps we can be erased from someone's life; that a relationship can be going fine, and that you can wake up next to someone and go about your day as normal and then, somehow, never see or hear from them again. The unreality lends itself both to intense and fleeting connection where a cord can be cut at the slightest intrusion of real life, and to the difficulty of building true, solid foundations. But how do we know if what we are making is real or ephemeral? How do we relearn intimacy without spooking (no pun intended) ourselves, and the people we are involved with; how can we trust, when these behaviors are so widespread now that we essentially have to accept we’ll experience them, in both our friendships and romantic relationships? Rather than create our own ghost stories, or fatalistically assume that’s how things are going to go, perhaps it’s time to be honest with others and ourselves about the times when we are feeling spooked—to take the time to listen and observe rather than disappearing without a trace.

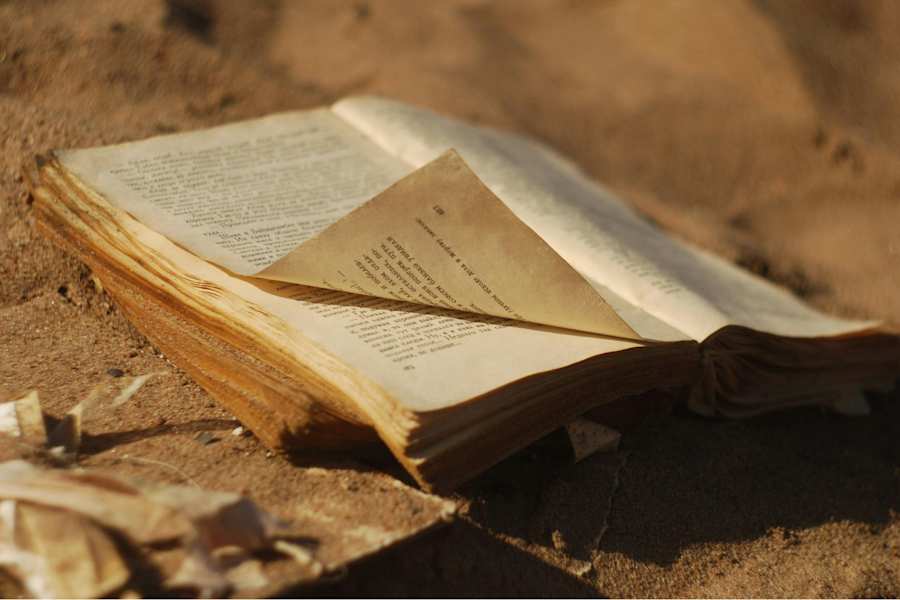

Past the talking stage is the reading stage. Ed Luker looks between the lines to find out what makes sharing words with new and old lovers so titillating.

When your eyes get tired of reading through the literary canon, Luna Adler suggests turning to romantasy.

A brief history of the literary daddy and age-gap relationships.