179 East 71st Street, New York

Evenings with Saul Steinberg and Hedda Sterne

Download Feeld

A constellation of experiences, a constant negoation of language: Jamie Lauren Keiles, journalist and author of the forthcoming The Third Person, takes us through the history of being non-binary.

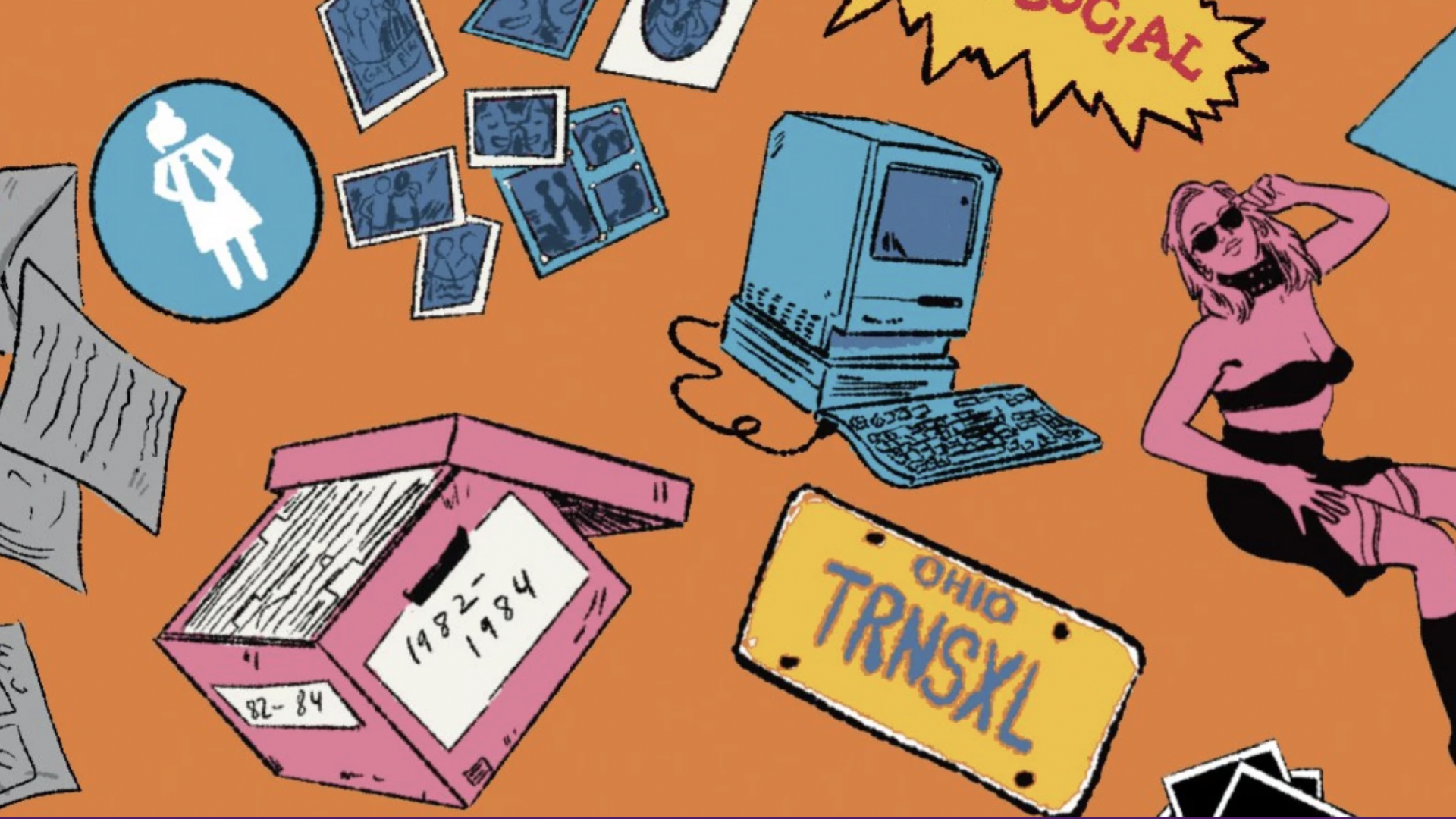

There is a recent, and often, unseen history to non-binary identity that requires a certain amount of effort to unearth. Jamie Lauren Keiles, the author of The Third Person, a book on a history of being non-binary in America forthcoming from Farrar, Straus and Giroux, is doing exactly that: bringing the ephemera of trans and non-binary histories from the 1980s through the early days of the internet out of archives, collections, libraries, and universities, and preparing to share what they’ve discovered with their readers.

In the meantime, however, there’s their Instagram account, sexchange.tbt. “Working on a book is a lonely process,” Keiles told me when I caught up with them over the phone, them being situated in a Brooklyn park and myself at home at the dining room table. “You’re getting deep into one subject, but you don’t really have anyone to talk about it with.” A contributing writer for the New York Times Magazine, Keiles has profiled Adam Sandler, Mike Gravel, and Jacquline Novak. The thoughtfulness and wit they bring through these interviews also lends itself well to their illuminating research into the treasure trove that is their ongoing digital trans history archive.

To stay connected during this lonely time, Keiles started posting some of the material sharing an assortment of images that are, by turns, comedic, heart warming, and hot. For instance, a few recent posts include a Backpage ad for a porn film from 1998, a photo from a trans rights protest in 1975, and a 1996 flier for a Pride sale on Dirt Devil vacuum cleaners. But it is the especially endearing posts about community and fun that have proven most popular with their followers, which, at last count, numbered approximately 8,000. They’ve learned to predict what people will like, and remain surprised by the difference between what they enjoy and their followers don’t.

As with anything, like Keiles says below, sexchange.tbt is a kind of negotiation between writer and reader: the bridge between Keiles’ process and the community their work is ultimately for. In our conversation, Keiles and I spoke about the limits of language, the repetitions of history, and why the internet, in many ways, sucks.

I was doing a lot of archival research, sometimes in person, going to different university libraries and their special collections, and sometimes online. I’m mostly using the digital trans archive, which is a great resource that aggregates lots of collections and libraries. I didn’t want to clog up my personal Instagram by posting constantly about my work, so I decided to make an account to share cool stuff I found. It’s really taken off. I’m mostly interested in the 1980s up until 2010, because I feel like this is the least well-circulated pool of content. Recent trans history hasn’t been written about as much; there’s kind of a gap between, like, the 1970s, and today. It’s like there was Marsha P. Johnson, and then all of a sudden, the present.

Early internet history—when trans people started coming online in the early 1990s—they were organizing on AOL, through a trans community forum. A lot of that is lost because people didn't think of it as something worth archiving.

Yes and no. A lot of the American trans history kind of starts in the1950s, with Christine Jorgensen, who was a huge media celebrity. She went abroad to have sexual reassignment surgery and then came back to the United States, becoming a phenomenon, and so that’s a very well covered period. And a lot of the ephemera from the 1950s, '60s, and '70s deals with a very medicalized aspect of transness.

Then you also have what were called, at the time, “heterosexual crossdressers:” people living part time in a cross-gender life. These two categories existed very separately, but neither of them speak to how we currently understand transness. Social media-wise, they're not very clickable. In the 90s, you start having people come together more self-reflexively, deciding we are the trans community and we're all the different weirdos that have collected under the same umbrella. That’s when it starts to resemble the world we have today, and makes this time period of the 1990s especially suitable for social media.

When I was going through the sexchange.tbt feed, I was thinking about how the discourse of this period you’re describing is very similar to the discourse of the present. I feel the same way when I notice that Tik-Tok has resurfaced the same discourse present on Tumblr a decade prior. What do you think about these cycles that keep resurfacing?

It is really interesting, because if you hang around in the trans world long enough you see that things reoccur really quickly. There’s a couple of things: there's the fact that for the first maybe, 30 or 40 years of there being ‘transsexuals’ in America, it was extremely discouraged to be publicly out as such. There were some community newsletters, but there wasn't a real impetus to document people's lives. Access to trans history is a little bit young as a field.

Then, also, it's not like other communities. For example, for the most part, Jewish people are born Jewish, and they start receiving their history and culture from childhood, whereas a lot of people become trans at some later point in their life. So there are always new people coming into it and they haven't had these conversations.

Then there's just the thing of terms that my parent’s generation will use that are not going to be the terms that I necessarily feel represent my experience. Language has always been reconfigured. It makes a lot of sense that the conversations reoccur, but it does get a little bit exhausting.

‘Transsexual’ goes in and out of style. When I was younger, I was hearing about people having a sex change. It was this very sensationalized thing that you'd see on, like, late-night television. Then when I was an adolescent, you had ‘transgender’ really circulating as the official term you're meant to use.

I feel like I became trans under the auspices of transgender. Now, I think because there's an unclear relationship between what it is to be non-binary and transgender, a lot of people that very clearly do not see themselves as non-binary are moving towards identifying as transsexual, as it describes a very specific experience of transition. Even though words come back, they change meanings. I don't think you ever arrive at a point where there's stable ground. I think it's a constant negotiation.

Probably both. I like to think of it as a sort of constellation of experiences. You have sexology in the late 1800s, and there's all these different phenomena that people are trying to give names to. Some of them are just men having sex with men. Some of them are being effeminate. Some of them are wanting to change their body through surgery.

From the 1850’s, essentially, until the present, people are always just figuring out ways to regroup those experiences. Sometimes we call the experience gay, sometimes we call it being an invert, sometimes we call it being transsexual. They're all slightly different each time, but they have these sorts of overlapping criteria. I don't think there's a constant spirit of experience of transness that exists through time. But I do think there's these recurring themes, and there are aspects of the experience that are consistent: having a feeling of dysphoria about your body, or feeling weird about your social roles.

As I discuss in my upcoming book, the thing that feels most authentically new to me is there’s a new group of people that call themselves non-binary. There might not have been a category throughout history for those people to articulate that relation to their identity.

I'm very interested in the distinction between what performs well on social media versus what doesn't. I personally like things that are essentially porn—I like things like a gender-bender hotline for a horny person to call into and talk to a person for sex. I love these ads, the graphics and the imagery, but I’ve noticed other people don’t always. I don't think people like things that are highly sexualized on social media. I think there's something about the relationship between trans people being sexualized, maybe a bit against our will…and then it just doesn't perform well on social media. Those that do perform well are people who have anything that is, for instance, a pin that says I love transsexuals. People like pictures of people hanging out in the 90s, which I just can't get enough of as well.

If you go on the digital trans archive, there's tons of scans of porn magazines that serve this dual community function. Because there are people reading that want to have sex with trans women, but also trans women are reading them and using them to get in touch with each other.

Not yet, but I'm really scared it's going to happen. I’ve noticed a lot of other trans history accounts—or just people that make art about trans subject matter—and they're constantly getting deleted and having to repost.

Transgender Tapestry, which had a lot of different names over the years: Transvestite Transsexual Tapestry, and just Tapestry. It ran really long, starting in the 1970s, and up until about 2005. It was the only glossy, full color trans magazine that wasn't a sex magazine. It's really good because you get a lot of the community drama. Once you start reading it regularly, you can follow all the different characters.

I also really liked this one newsletter called 20 Minutes that came out of Massachusetts. It has a really bitchy rude tone where they're constantly talking shit about each other, a bit like supermarket tabloids. I love this sort of thing, but people on the account don't like that stuff. And they don't like transphobic camp TV things from the 90s, which I also think are funny.

For sure. I think because the news lately is so depressing. People just want a few things that are trans people being happy and goofing around and falling in love. And so I try to keep it pretty positive.

I believe the website "Susan's Place," which was on Geo Cities originally, and was a big directory of all trans women's homepages and crossdressers homepages is still operating. Pretty much all of the print magazines and newsletters folded with the Internet. And in some of the final issues, you can really see people grappling with that and saying “fuck the internet, it'll never replace what we've created.” They had built up a lot of infrastructure in the 1980s and 1990s and then the Internet came and all of a sudden it was scattered to the wind.

Original Plumbing ran until pretty recently. It was a trans guy culture mag that contained a lot on gay trans guy cruising and bathhouses, like, just stuff that doesn't exist today. And that's the most recent one, but I think it folded in maybe 2019.

People constantly comment things like, “I wish we still had this today,” and I'm always like, I don't know, you could, like, go try to do it? A lot of it just takes time and energy… even I probably spend a good 35 minutes a day running the account. That's a pretty low lift.

To end, I’d just say, I really like doing collaborations, and I've been trying to do more.

So if anyone has cool archival material, or a project they're trying to promote, I'm really into the idea of making it an account for sharing other people's work too.

Evenings with Saul Steinberg and Hedda Sterne

Aren't we all just part of a great literary, liberatory tradition?