The “whale tail” thong, there to be seen, winks seductively at whomever makes eye contact.

It carries the confidence of the brassy bartender everyone has a crush on, the blatant sexuality of a Playboy found at the back of a closet, the glossy charisma of an early aughts pop star. What makes a thong a “whale tail”? Technically any thong can be one: the phrase describes a phenomenon, when the straps of the thong intentionally rise above a pair of pants, a strappy silhouette over hip bones meets above the ass in the joining of fabric that divides the wearer’s cheeks. The whale tail is most traditionally associated with that frisky little triangle that serves as an angular bullseye, drawing attention to one’s ass. It is a bold declaration that one is wearing a thong, and that the thong is meant to be seen.

How we dress ourselves tells a story about who we think we are, and how we want others to see us. Lingerie is traditionally worn as a secret beneath the clothing that conveys a self to the outside world. While a visible bra underneath a sheer shirt, or even a bra as a shirt, has become more normalized, the intentional incorporation of a visible thong into an outfit is still less common, and almost guaranteed to cause a double take. A whale tail draws the eye, and advertises what the minimal fabric is that separates the wearer from being completely nude. At its essence, the whale tail is sexy exactly because it brings the private into the public. To wear a whale tail is to wear a secret, but decide to tell anyone who will listen.

For many millennials like myself, the whale tail moment was when Manny Santos debuted her bad-girl persona in season three, episode three of Degrassi “U Got The Look.” Her dark denim jeans were slung low on her hips but most importantly: her thong. Manny’s thong was a bright, electric blue, with iridescent gems decorating the waistband. It was the same Y2K blue as Apple’s flirty foray into translucent computers with a colored accent. The same blue as the plastic beaded doorway I begged for from Claire’s. The thong rode a few inches above her hips, prominently emphasized by a cropped shirt, her torso a blank, uncovered canvas for the thong to pop against her flat stomach. Manny had previously been a mousy good girl, and her blue thong was the exclamation point on her transformation to being a babe. As she strolled through the high school halls, everyone turned to stare, mouths agape. The thong was the key to unlock Manny’s performance of a confident sexuality, as she walked down the locker-clad hallway towards womanhood.

I acquired my first thong at a Victoria’s Secret in San Antonio, Texas in the early 2000s in middle school. The group of girls I was at the mall with all egged each other on, desperate to wear something that would make us seem—and most importantly, feel—adult and sophisticated and mature, things we very much were not. My thong was tiny, a light blue the color of Paris Hilton’s eyes, with pink polka dots on the elastic band. When I put it on, it wasn’t comfortable but I liked that it reminded me of its presence throughout the day. It made me feel like I was in control of my body—which I both was and wasn’t.

While the whale tail is most commonly associated with the late ’90s and early 2000s, the origin of the G-string actually goes back to 1930s burlesque. Dancers used to perform topless or completely nude, and the G-string allowed for a way to be legally compliant with strictures against public nudity while still showing the goods. The mayor of New York City at the time, Fiorello La Guardia, opposed burlesque, which was a major aspect of public entertainment during the Great Depression. La Guardia declared that burlesque was a sign of “public immorality” and demanded that the nude dancers cover up, particularly when New York hosted the World Fair in 1939 and many tourists would be visiting the city, a demand that illustrates how the thong’s history has long been intertwined with that of men censoring women’s bodies. Thongs came to the beach in the 1960s and 1970s, but wouldn’t make their street debut until the 1990s. Cher popularized a thong bodysuit in her music video for “If I Could Turn Back Time,” which debuted in 1989. In it, a 43 year-old-Cher dances on a military boat in a sheer bodysuit with a satin-y black ribbon that covers her crotch and butt crack. Over the bodysuit, she wore a black motorcycle leather jacket and a silver belt that looks like a large charm bracelet. Her bodysuit holds up black thigh high stockings. The music video was initially banned by MTV because of Cher’s visible rear. It was later only permitted to play after 9 PM. A few years later, visible thongs would hit the fashion runway.

The whale tail made its fashion debut as a part of the brilliant and edgy designer responsible for Madonna’s cone bra, Jean Paul Gaultier’s Spring 1997 collection. Gucci would also incorporate the visible thong into its late ’90s collections once Tom Ford joined the fashion house. It was the late ’90s, early ’00s, the heyday of thongs. Sisqó’s “The Thong Song” peaked at number three on the Billboard charts in May of 2001: a melodic ode to the iconic item of clothing (the line “let me see that thong” will now be stuck in my head for the foreseeable future). At the 2000s VMAs, Britney Spears performed “Satisfaction” which slithered its way into a provocative “Oops! I Did It Again,” during which she popped off her modest dark suit to reveal a nude bedazzled bodysuit with strappy details that suggested a thong. This performance marked Britney’s official pivot in a sexier direction, amplifying her already prominent sex appeal. Younger celebrities like Paris Hilton and Christina Aguilera were photographed wearing visible thongs, which helped popularize the trend with young women. Gillian Anderson, thirty-one at the time, attended the Oscars after party in a slinky navy dress with an open back, revealing the black mesh triangle of a thong covering her tail bone.

Then, the dark ages. The whale tail went dormant for nearly twenty years.But recently it-girl Hailey Bieber led a fashion whale watch when she wore a baby pink Alexander Wang gown with a visible G-string to the 2019 Met Gala, the silver word “wang” gleaming from her tan lower back. The supermodel Bella Hadid wore a visible thong in Versace’s Spring 2020 show and has continued to sport the look in various streetwear paparazzi photos.

Recently, I decided to do a bit of research. So many millennial women, cis and trans, have a Thong Story. Many like myself had stolen or bought one from Victoria’s Secret or The Gap, eager to own a tangible piece of eroticism. One woman, answering a request I posted to Instagram for people to tell me about their relationships to the underwear style, told me that her thong was “a physical representation of everything happening as a super sexually repressed teenager,” that wearing one made her feel “turned on and rebellious.” Another told me that the thongs she and her friends bought at Victoria’s Secret “animated their sexuality” as they performed what they thought being hot was for—boys—which largely consisted of making out with each other. I heard multiple stories of people washing their singular thong in the sink, night after night, just to be able to wear it again the next day because of the confidence boost it gave them. The thong was a private experience that one could choose to make public (or not—if you bent over too cavalierly in the age of the incredibly low rise jeans, it might just decide to reveal itself).

The whale tail is officially making a comeback. To wear a thong is to don a piece of fabric that has a history of censorship and sexuality and rebellion. To proudly expose a whale tail is to emanate confidence and ownership over one’s body. After a decade of high waisted everything, the pendulum has swung the opposite way. We’re heading back towards the era of the low rise, a moment that dovetails with a widespread re-examination of how we treated female celebrities in the early 2000s like Jessica Simpson, Britney Spears, and Pamela Anderson. These are all women who faced misogynistic scrutiny in the media and whom we are regarding more empathetically, despite (and maybe because) the fact that all of these women were highly sexualized. To sport the whale tail is a nod to knowing you are playing the game that the patriarchy makes us play. It is to participate in a lineage of cheeky sexuality, a dissolution of the barrier between private and public. It is a sticky lip-glossed kiss, the lingering smell of Victoria’s Secret perfume, another way to perform the impossible and joyful and infuriating and erotic pleasure of being a woman.

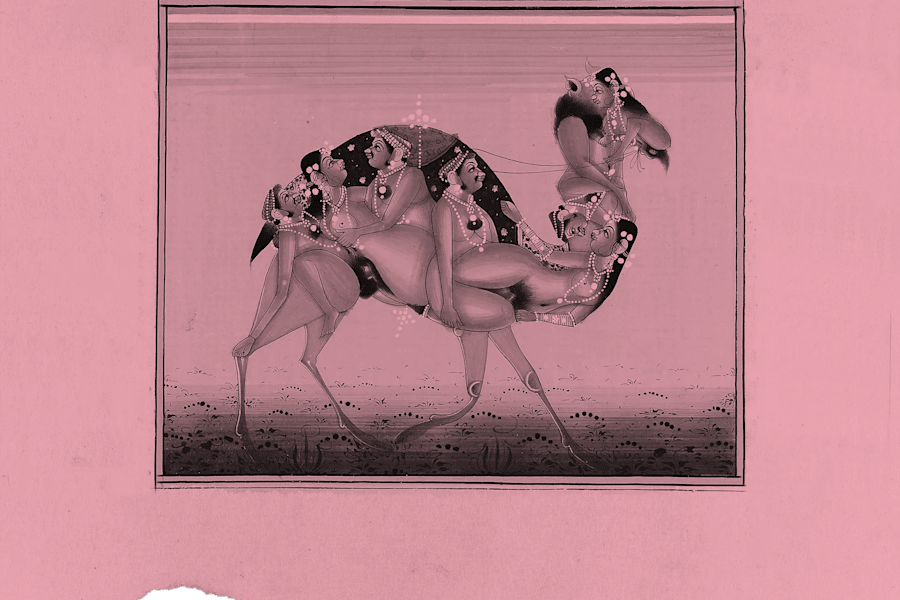

Art by Carol Civre.