Puppies Puppies brings “Nothing New,” and with it, the unseen and the obvious, to the New Museum

There were no Puppies Puppies posters in the gift shop. Not even a little booklet with short essays on the work and a selective CV with full-color images. Disappointing, considering how the artist’s work is preoccupied with replication, social media, and image-making. Besides, I wanted a memento to remember the show by. On my wall I have keepsakes from art exhibitions that particularly struck me—reminders of the way art can pierce the veil of the mundane.

Puppies Puppies, also known as Jade Kuriki-Olivo, has become an outspoken advocate for the promise of visibility. Her work consistently interrogates the boundaries of self-representation. Her early work frequently featured costumes—SpongeBob, Minions, Gollum, Lady Liberty, Freddy Krueger—obscuring her identity before turning toward bold self-representation like the nude sculpture of herself that appeared at Art Basel in Switzerland entitled “Woman.” Afterward she received death threats for daring to deputize a trans body as “a woman.” Increased visibility has not secured a safer world for trans women.

Kuriki-Olivo has elaborated on the stakes of putting her body on the line: “Sometimes, I wish that I didn’t have to make work about my identity…but I just keep telling myself that you have to be hypervisible, because it means something different to hide.” She would know, having experienced both sides of the dichotomy. In a recent New York Times interview she said she “didn’t have a choice.” She believes the attack on trans women can nevertheless still be fought through visibility wedded to direct action. Certainly her participation in the 2020 Stonewall Protests that centered Black trans women is a powerful demonstration of such concentrated visibility. This focus on collectivity is present across her work. She often passes the baton to other artists or turns institutions into community centers, as she did in the pop-up HIV testing center that was “Body Fluid (Blood).” Elsewhere, she displayed a friend’s GoFundMe for transition-related costs in a gallery and donated the proceeds.

Her newest show, “Nothing New,” opened on October 12 at the New Museum in Manhattan and runs until March 3. The exhibition claims to hinge on the artist’s presence—the show advertises her attendance in the gallery space, as well as a live-stream of the artist going about her day. Puppies Puppies continues to toy with the politics of representation despite her identity no longer being a secret. Even so, she finds ways to obscure herself.

The institution’s first floor gallery has been replaced by a surreal bedroom comprised almost entirely of green furniture. Those walking by in the lobby can peer in and watch. A bed, a bubbly postmodern chair, grassy rugs, stools, a rack of clothes, glowing lantern orbs, a rack of dishes, and a drafting table. Two transitional screens sit on either side of the bedroom. On one side is a rock garden with a Torii Gate and on the other, carefully trimmed CBD hemp plants. MRI scans of the brain tumor Kuriki-Olivo had removed in 2010 are displayed on the glass wall separating the bedroom from the gallery. The New Museum’s cafe has been stocked with entirely green products: sour cream and onion Lay’s potato chips, canned green beans, Ito En green tea. Green was her father’s favorite color.

Above the lobby three flags hang: the Intersex-Inclusive Progress Pride Flag, the Resistance Flag of Borikén, and the Taíno flag. Growing up in Texas with a Japanese mother and a Taíno father, Kuriki-Olivo has described the difficulty of coming of age in a racist, transphobic environment. Hanging these flags in a major institution means something, as obvious as it may seem. Finally, a monitor displays the green bedroom to the other side of the lobby and can apparently link to Kuriki-Olivo’s phone in order to livestream in real time. This self-surveillance recalls the glory days of e-girls and camming, where someone is paying personal attention to an imagined viewer and the world has been remade kawaii. But Kuriki-Olivo is not a cis white girl playing on our affections with appropriated fandom culture. She’s often disinterested in the world when it’s merely scrutinizing her body, even as she herself deploys it.

The exhibition was originally intended to focus on four months of 24/7 surveillance of Puppies Puppies as she went about her day, both in and outside the museum. She was not present at the time I attended the show (nor, it seems, during the many times critic Johanna Fateman visited), and I never saw the livestream flicker. I asked the gift shop attendant what the performance was like, when Puppies Puppies was actually there. She told me it’s not a continuous performance but that Puppies Puppies came a few times a week, sometimes with friends, and did occasionally livestream her whereabouts. I asked if she slept in the museum. “No,” she answered politely.

While it seems she wasn’t able to live full-time in the New Museum, Kuriki-Olivo did once live in a gallery. In 2017, “Green (Ghosts),” she, her husband, and dog relocated to Overduin & Co on Sunset Boulevard. Apparently during that time, she did actually sleep in the gallery space. This is the same work as the woman who once said, “I romanticized disappearing.” Just as narcissism pivots on both self-aggrandizement and self-effacement, “Nothing New” demonstrates how visibility relies on presence and absence. Representation does matter—but how?

Image courtesy of The New Museum. Photography by Dario Lasagni.

Image courtesy of The New Museum. Photography by Dario Lasagni.

For institutions, performance art has been historically fraught. While often devalued, some strides have been made, “Liberty (Liberté),” Puppies Puppies’ performance as Lady Liberty in 2017, became the first performance artwork to enter the Whitney Museum’s permanent collection. But her attempts to expand the possibilities of public art spaces have not come without a price: when she ran a gala to honor trans women of color at Performance Space, something seemed to strain the curator’s word choice when describing the experience. “Jade really challenged us,” Pati Hertling told the New York Times.

Kuriki-Olivo’s work takes on a utopian edge in our virulently racist and homophobic nation—playing with representation even when the dangers in doing so are perilous and the rewards uncertain. Flying Pride flags may seem almost gauche in an irony-pilled world, but there’s still power in pushing an institution just to say the word “trans.” Certainly, Kuriki-Olivo uses utopia as a weapon, brandishing death, exposure, and self-documentation to immerse the viewer in a trans aesthetic. There’s no one trans aesthetic—but the dialectic of presence and absence is paramount. (Think, for instance, of the trans artist SOPHIE, who routinely hid her face before “coming out” full-force in the playfully nude “It’s Okay To Cry” music video. “Everybody’s got to own their body,” she croons on HEAV3N Suspended.) Even anecdotally, I know a large number of trans people who have Instagrams full of hieroglyphics, pictures of roses, protest infographics, beanie babies, and almost no selfies. This is a far cry from sponsored coming-out posts.

Absence becomes final, brought to its furthest conclusion in death. While Puppies Puppies plays peek-a-boo with costumes or livestreams, she has also imagined what the end looks like. She has lain in a coffin, engaged with ideas of the plague, and held a funeral for her deadname. If the joke of her current show’s title, “Nothing New,” refers to how little the artist is actually present—not participating after all in a voyeuristic panorama of her life—then it’s certainly not unprecedented. While some of her work recalls Rirkrit Tiravanija or Marina Abramović, she’s also a bit of a punk, bringing the aesthetics of sex work, marijuana, and transness into the gallery with a wink. She is not so deadly serious. Until she is. In a 2021 Artforum column she wrote: “Trans women often don’t live as long as other people. It creates a different way of relating to time.”

It would be interesting to see Kuriki-Olivo live her life under constant surveillance—to critique and seduce us with her use of social media aesthetics. It certainly felt like a bit of a letdown not to see the artist in the flesh. The idea that she might have sex in front of a live audience was fascinating, especially considering the current panic over public sex. But this may not be the point. Or I simply have not visited the New Museum enough to have seen her. It is curious that the New Museum has programmed her next to Judy Chicago, a canonical cis white woman feminist artist—as if to try and introduce some sort of corrective balance in how the institution understands and supports the cis-dominated canon of feminist art.

All the pieces Puppies Puppies has fabricated as a part of the green room have long, multiple parenthetical names. The glass that separates her bedroom from the viewers is called: “transitioning screen (transitioningglass)(transparency) (changing opacity)(public view)(privacy)(censoring)(online/ offline).” There’s an all-lower case, highly fragmented poetic element to her naming conventions—another late millenial/Gen Z online aesthetic. The CBD hemp plants have a “short” name—that is not actually so short, but invokes Shintoism and the brain tumor removal surgery she received—as well as a longer name that is, in essence, a poem. “I felt as if I was walking in a fog/the fog enveloped my brain and followed me with every interaction… I imagined myself taking a flight alone and falling to the ground in the aisle,” one section reads.

A portion of her bedroom is named “(trans femmes dreaming of their future in the comfort of their bed in “paris is burning”).” Invoking the canonical trans film and the ineffable in the same breath, she flirts with cosmic oblivions. Such hope can distort intangible presence and mourn the limits of tangible absence, both online and off.

Grace Byron is a writer from the Midwest based in Queens. Her writing has appeared in The Cut, Bookforum, The Nation, and The Baffler among other outlets. Find her @emotrophywife.

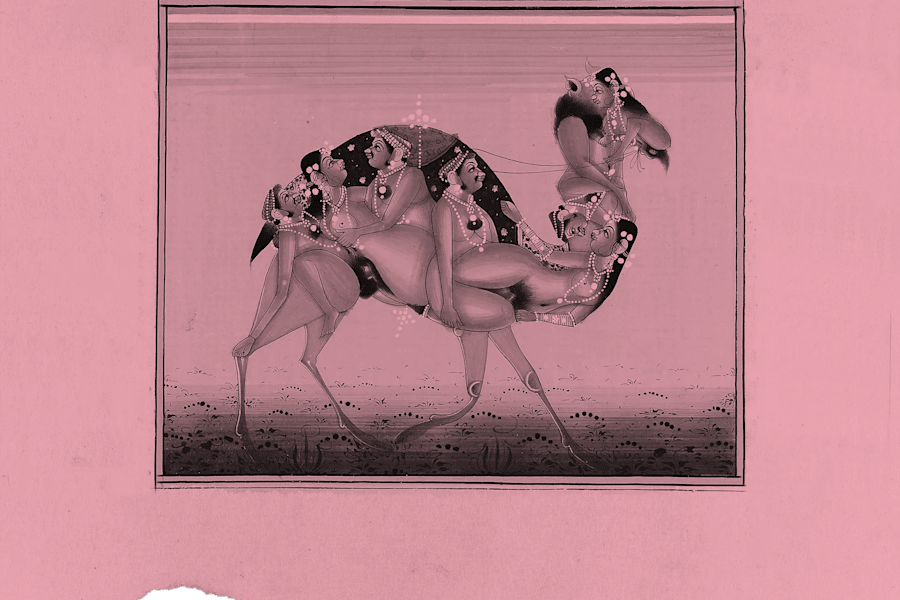

Images courtesy of The New Museum.