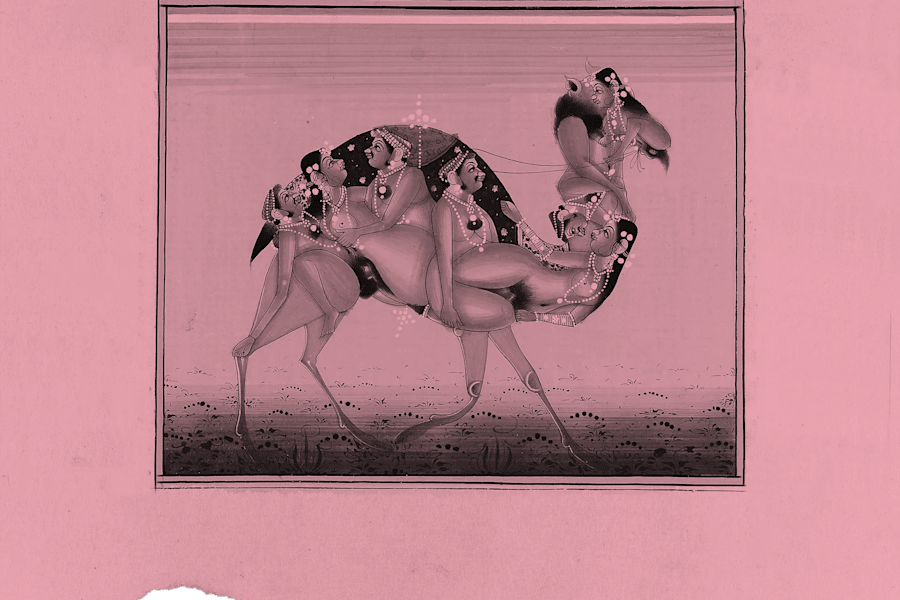

Barbara Stanwyck and Henry Fonda in "The Lady Eve," 1941. Courtesy of Universal Studios Licensing LLC.

How deeply is the American sense of longing, and living, imagined on the big screen? Justin Smith-Ruiu dissects Stanley Cavell’s "Pursuits of Happiness" and the movies that shaped his work—and us.

I have recently watched or rewatched all seven of the classic films to which Stanley Cavell dedicates a chapter each in his 1981 book Pursuits of Happiness. It is a study of the Hollywood Golden Age genre of the comedy of remarriage, featuring works by Howard Hawks, Preston Sturges, George Cukor, Frank Capra, and Leo McCarey, variously starring Clark Gable, Cary Grant, Katharine Hepburn, Irene Dunne, Spencer Tracy, Jimmy Stewart, Henry Fonda, Ralph Bellamy, and others.

Cavell presents these films, all of which appeared between 1934 and 1949, as a sort of imaginary canon, the most accomplished representatives of a new chapter in the history of English-language comedy. These are indeed exceptionally well-curated works and, watching them, I was consistently surprised by how completely engrossed they kept me, and by how deeply I enjoyed myself.

He also knows how to articulate his method, moving so fluidly and naturally between philosophy and film studies. In a crucial appendix to Pursuits of Happiness, Cavell positions himself in a lineage that includes the German critic Walter Benjamin and the American intellectual Robert Warshow, both of whom, in very different ways, were concerned with the question of the place of film within aesthetics and art criticism. Benjamin was primarily focused upon film as a new technological possibility alongside other similar ones in the era of mechanical reproducibility, while Warshow, in a more directly Cavellian vein, was concerned with particular films, and whether it is possible to assess them in a language and with standards developed for other media.

Early on in film history, its inclusion within the purview of classical aesthetics was controversial for its mass appeal—an appeal that was exciting to revolutionaries and the early avant-garde, and that did much to expose the elitism and exclusivity that helped to maintain the aura of interest around the objects of criticism in other art-forms. But beyond this concern, as to what, as critics, we are to make of film, Cavell astutely identifies another more profound line of thinking. He seeks to understand whether and to what extent film, and its predecessor photography, do not so much stand as candidates for inclusion in the scope of art criticism and of philosophical aesthetics, but rather mark a fundamental rupture in the history of art itself. Thus, Benjamin writes, quoted by Cavell, that the primary question is whether photography, and therefore also film, “[has] not transformed the entire nature of art” (266).

Cavell sees his own turn to the philosophy of film as a natural evolution of his place in the tradition of ordinary language philosophy, which he traces back somewhat unusually through J. L. Austin and Ludwig Wittgenstein to Ralph Waldo Emerson. The appeal to ordinary language as a source of philosophical insights has seen different philosophers investigating different domains of speech: Austin was interested in quotidian talk of “medium-sized dry goods”; Wittgenstein wanted to know what people really meant when, say, they shout “Slab!” For Cavell, concern for ordinary language is in part channeled into attention to new vernacular strains of poetry and art, what Emerson describes in “The American Scholar” of 1837 as “the literature of the poor, the feelings of the child, the philosophy of the street, the meaning of household life” (14). In this Cavell sees a method, that of “sitting at the feet” of the familiar and low, that he fruitfully extended to his art form of interest, one Emerson could not have anticipated. In this connection Cavell, perhaps unusually among film scholars, is above all interested in dialogue, in the “language of film” in the most literal sense, rather than in “cinematic language” as it had evolved by the 1930s to express ideas, intentions, and other inner states through frame composition, camera angle, editing, and other techniques. Cavell is well aware of the relative poverty of the language of film in the narrow sense, particularly when it is written out on paper. Analyzing the things said in a Golden Age Hollywood movie will not reveal the full depths of the cinematic art to you, but it is a good place to start, especially for an ordinary language philosopher.

Like Warshow, Cavell is also interested in particular films as objects of mass appeal, thus as “movies,” as objects of serious criticism, and, finally, as starting points of serious theoretical reflection. As to the historical importance of the particular films he has selected, Cavell characterizes them as a revival, after long dormancy, of a comedic genealogy that extends back to Shakespeare’s greatest achievements in that genre. The borderline non-comedy The Winter’s Tale seems to have passed on its DNA most directly, of all seven films under discussion, to Preston Sturges’s The Lady Eve (1941). Shakespeare’s unusual romance violates the Aristotelian theory of classical unities, which theorized what bound the sequence of events in any successful drama, by inserting a sixteen-year delay between Hermione’s disappearance and the subsequent quickening of a statue built in her honor, which causes Leontes to fall back in love with her and precipitates their happy reunion. What is this strange appendix that Shakespeare adds, giving a happy ending to a story that had otherwise been presented as a sequence of arduous psychological trials?

In Sturges’s film, the herpetologist and wealthy beer heir Charles Pike, played by Henry Fonda, takes a steamer back from the Amazon to New York, and on board meets a father-and-daughter team of card sharps. The scientist falls in love with the woman, Jean Harrington, played by Barbara Stanwyck, but before the cruise is over he learns her true identity and calls it off. Back at the Pike estate, the same woman tracks him down and enters his family’s social set disguised as a countess. Initially it seems to him he knows her, but she refutes that theory, and he falls in love again. They marry, but her duplicity and deviance soon begin to show, and he leaves her to return to South America. On the same ship back, he meets her once more, returned to her original identity, and declares he’s in love with her, but is now, regrettably, married. She reveals that she is married as well—to him—and that’s the happy ending.

Along with Cukor’s The Philadelphia Story (1940), The Lady Eve offers a paradigmatic instance of the Golden Age Hollywood comedy of remarriage as genre and as formula. Though in very different ways, the dramatic resolution in each of these films consists in a reaffirmation of an initial romance, rather than a permanent rupture leading to some new romance. Perhaps the ultimate negation of the comedy of remarriage arrives from France a decade later, with Louis Malle’s Les Amants (1958). Here the story begins with a married woman, played by Jeanne Moreau, who already has a lover, and who ends up leaving both her husband and his alternate for yet another late-arriving interloper, who gives her mainstream cinema’s first on-screen orgasm.

Post-war French cinema revives the spirit of 18th-century libertinism, but adds a significant dose of anomie: we all know Jeanne is really only looking for a way to fill up her meaningless existence, her “hole in being,” to quote Sartre, and that she will never be happy. While Charles and Jean are probably going to be happy enough, forever after, and even their worst fights will pop with clever one-liners that, even at their most hurtful, still serve to reinforce their love.

Comedies of remarriage were born out of that curious American blend of puritanism and prurience that has always defined us. Divorce was still mostly a great moral failure, especially for women, unless of course, as Edith Wharton wrote in 1905, the divorcée “had shown signs of penitence by being re-married to the very wealthy.” After the Hays Code was enacted in 1934, and the major studios committed themselves to prudent self-censorship, final and definitive divorce shifted beyond the pale as a plot device for Hollywood movies. And yet even or perhaps especially under the Hays Code regime, to depict the conflictual stage in the life of a woman who is at least in principle prepared to go through with a divorce offered a way of having your cake and eating it: devote the bulk of the narrative to depiction of bold and independent femmes d’esprit, but tie things up with a reaffirmation of the solidity and sanctity of the institution that keeps our society healthy and whole.

Cavell’s seven films, in this regard, are less noteworthy, to my mind, for whatever they achieve in the resurrection of flagging tradition than for the ideological position they take up in their cultural and political moment. And they are remarkable for the consequences of this positioning for the subsequent history of American moviemaking, and of American culture as a whole. These films consistently portray a certain amount of subversiveness, but it is subversion dialed down to the level of quirk, libertinism domesticated into mere “spunk.” One way of seeing this is to suppose that spunk is the Trojan horse by which true subversion makes its way into the broader culture; one might also suspect, or fear, that whatever makes it into the broader culture by this vehicle will be so thoroughly diluted in the process as to be rendered incapable of triggering meaningful social change.

No one embodies the ideal of the spunky “new woman” more fully than Katharine Hepburn, in her successive turns in Bringing Up Baby (1938) and The Philadelphia Story, both featuring Cary Grant as her love interest, and in Adam’s Rib (1949), with an already tired-looking but still charismatic Spencer Tracy. The first two of these, directed by Hawks and Cukor respectively, show our leading lady as an indomitable spirit, who nonetheless longs for some sense of normalcy, of living according to familiar expectation, in true love followed by marriage. Yet after as before her redemption, she plainly intends to continue her thoroughly modern pursuits, which are mostly just leisure activities like golf and horseback riding, rather than, say, fighting for reproductive rights or equal pay. That’s progress, American style: where desire for radical social change is consistently channeled into a celebration of lifestyles and personalities instead (which admittedly may also be one dimension of the more general struggle for the basic political right of freedom).

Cavell’s films, he argues, relate human struggles forged in the crucible of the Great Depression, and their opulent and rarefied social settings represent a fantasy world that at least offered a temporary balm for the suffering masses. I see the consistent focus of Golden Age Hollywood on the wealthiest American settings somewhat differently, and here I have trouble not recalling John Steinbeck’s apt explanation of why working-class Americans are so hesitant to think of themselves as part of the global proletariat. For them, Steinbeck thinks, even the most downtrodden and exploited Dust Bowl migrant is really only a “temporarily embarrassed capitalist.” Cavell is by no means inattentive to the class dimensions of the films he analyzes, nor to the realities of class in the time and place these films were made. As he rightly observes, in the different films the wealth on display comes through in different forms. Katharine Hepburn’s character Tracy, along with her family in The Philadelphia Story, are the closest thing Americans have produced to an aristocracy, and accordingly, they subvert the ordinary American expectation, as Thorstein Veblen described it, that the wealthy will be unable to enjoy their wealth unless they get to show it off. Tracy resides in a different universe than that of the conspicuous consumers; if you’re already on the social register, you will not yearn for coverage in the society pages of the newspaper.

I think it is likely, for the reason identified by Steinbeck, that the people who first watched these movies on the big screen did not see them as being specifically about rich people; they saw them as being about themselves. Or, at least, they thought of the lives depicted in them as worthy of aspiration, rather than as, say, a compelling argument for redistribution. There is indeed a significant expression of class consciousness in Jimmy Stewart’s character in The Philadelphia Story, or in Clark Gable’s in It Happened One Night (1934), or again in Cary Grant’s in His Girl Friday (1940), all of whom play hardened newspapermen looking for a scoop, all committed almost religiously to their life-calling as gadflies of the corrupt and powerful. But in the end this too is presented more as a lifestyle than as a cause, and it exists in a static harmony alongside the high-tone world of socialite daughters and their indulgent industrialist fathers.

The greatest artistic accomplishment among Cavell’s seven films is undoubtedly Frank Capra’s pre-Hays It Happened One Night, featuring Claudette Colbert as a wealthy daughter fleeing from her controlling father in Miami to go to New York by bus and to marry a fortune-seeking adventurer. On the way she meets a journalist, played by Clark Gable, who discerns her identity and who attaches to her in the hope of extracting a bombshell story, but ends up in love instead. The film’s greatness flows in part from its defiance of genre. It is not really a comedy of remarriage, but at most of a marriage called off and another one arranged instead. It is more properly a road movie, yet intriguingly the road runs not East-to-West, as we are accustomed to seeing in America, but South-to-North, Miami to New York, and through all the impoverished human waystations of the Depression along the way, through Georgia and the Carolinas and Virginia. There are bus depots, snack-bars, and proto-motels. There are mendicants and dysfunctional families and colorful characters full of folk-wisdom. This is the only of the films that even remotely looks like America, that gives any sign of wanting to look at America, as it was and as it is.

It Happened One Night is also, as Cavell, who was born in Atlanta, notes, the singular exception among these films, which otherwise portray the rigid social stratification of class as a natural and inflexible order. In one scene Clark Gable’s character asks the wealthy father of the young woman he has trailed for a reimbursement of his expenses. The father presumes that the scrappy journalist is asking to get paid off, only to learn that Gable’s entire bill comes to a grand total of $39.60. As Cavell observes, this character’s purpose, along with Henry David Thoreau’s, who built his home at Walden Pond for $28.12½, is “to distinguish themselves, with poker faces, from those who do not know what things cost, what life costs, who do not know what counts” (5). In this respect Capra’s film is the most radical, and indeed its politics could not possibly have survived the moral and political homogenizing effects of the Hays Code and the Second World War, which together shape so much of the sensibility of the later films discussed in the book.

Aristocrats and flashy nouveaux-riches alike are united, in mid-century America and its cinematic representations, by a love of leisure. Not long ago I watched the Elvis vehicle Viva Las Vegas (1964), and was alarmed by the totality of leisure’s reign in the film’s fictional universe. There is one scene where the race car driver Lucky Jackson (Elvis Presley) meets the father of his love interest Rusty (Ann-Margret), who lives on a houseboat near Hoover Dam. Lucky asks the old man, played by the ubiquitous William Demarest (who also has a turn in The Lady Eve as Mugsy, a role that Cavell describes as “the melancholy that comedy is meant to overcome” (69)), whether he would like to join the two of them for a helicopter ride, or perhaps for a jaunt in the speedboat they’ve just taken out for waterskiing. He tells them he’d love to, but he’s got to go meet his friends in the bowling league that evening. It is just non-stop in that world: the eternal cycle of divertissement! I had thought when I was watching this that the constant pursuit of such recreations was simply an artifact of uninspired screenwriting, but something hit me as I pushed through Cavell’s seven films: the universe of Viva Las Vegas was in fact constructed in the 1930s, and at that earlier time it brought into being the essential type of the middle-class American, the whole package of desires and aspirations that constitute this particular form of life.

Even if the lens through which all this unfolds is gently colored with satire, one comes away from it saying inwardly: “I should be more like this.” I realize now, in fact, what a tremendous debt my own mother’s speech habits and aspirations owe to Katharine Hepburn. She and her husband, my 89-year-old stepfather, still aspire to a variety of conversational wit in which the sensitive ear can hear resonances of 1930s Hollywood, though I long mistook it for a symptom of their having watched too many sit-coms. But Cheers and Murphy Brown and so on have turned out to be something like the Ayn Rand to Katharine Hepburn’s Nietzsche: the bargain-bin derivative products of what at its origin had been a truly new way of being modern.

Stanley Cavell was born nine years before my stepfather, both of them Jewish Americans whose formative years were spent in the shadow or in the aftermath of World War II. Both were raised in Sacramento, California, and were habitués of the same local movie theaters. (It is perfectly likely that the two of them shared a theater watching some of these films.) And both were shaped into consummate 20th-century Americans in the process. But while Cavell went on to a life of criticism that considered his own Americanness, and his own America, my stepfather mostly went on to a life of tennis, and golf, and rooting for the 49ers. (Members of the extended family have been known to retire early from their law firms, and to move to Las Vegas in order to volunteer to work as ushers at Raiders games, out of pure devotion to the team). To my stepfather, and the life-world I knew first, Viva Las Vegas, perhaps minus the rock-and-roll musical interludes, is simply reality. My mother, meanwhile, Sacramento-born, has taken up gardening, and when she tastes the snap-peas she has brought up from mere seeds, she declares: “Oh, they’re ever so sweet,” in that nearly extinct New England accent that is basically just English: It’s Katharine Hepburn, I now realize, still speaking through her, a ghost from the silver screen.

More than forty years ago, my mom and her close friend took me and the friend’s twin boys, my coevals, to see a matinee of On Golden Pond (1981), starring the now-elderly Henry Fonda and Katharine Hepburn in an adapted stage drama unfolding in an entirely different universe than the one confected for them in the 1930s. Cavell might have seen these same stars in the same theater decades before, though surprisingly On Golden Pond was Fonda and Hepburn’s first and only collaboration. We boys had no idea who these old people were, but our moms did their best to drive home to us their status as legends and the magnitude of their former fame.

Today, I believe that Katharine Hepburn is a pure ray of light from another world, and I believe the films Cavell chose to study in Pursuits of Happiness are themselves polished gems straight from our American dream factory. The entire purpose of this factory, which came into maturity in the inter-war period, has been to impose what we might call a regime of happiness, to make life better not by making life better, but by making life look better, by chasing away, with the promise of unending leisure, the horror of a vacuum such as Jeanne might have encountered face to face in Les Amants.

The movies have implanted a vision of the good life in us, installed a program of aspiration, shaped the words that come out of our very mouths, fixed the horizon of meaning that we do not cease to approach even as we approach death itself. Our lives were, fundamentally, the movies. These objects may indeed be approached through attention to ordinary language, but their real language, behind all the low dialogue, is Emersonian and not Austinian, casting us into a transcendent reality glimpsed only by imagination, and approached only by longing.