Text me when you’re done: An Ordinary Miracle

Anya Tchoupakov on a fever-dream of a musical fairytale and everyday magic.

When I was about 5 or 6, every Saturday I would accompany my mother to work. As a ballet teacher, she had her own school, but she often picked up weekend classes at other studios. When my father was on tour dancing or teaching in his own right, off I’d go with her—as ubiquitous a presence as her dance bag.

One particular studio was…weird. I remember black walls with hot-pink duct tape holding up competition photos and headshots of alumni, very little oxygen or light, low ceilings, and the thumping of dancing children from the closed-door studio all adding up to a horror-movie feeling.

Every Saturday at this eerie liminal studio, while munching on a Costco poppyseed muffin, I watched the same movie on a portable DVD player (which I considered the height of modern technology). The movie, An Ordinary Miracle, is a Soviet fever-dream of a musical fairytale that—although also funny, light-hearted, and beautiful—probably contributed to the somewhat surreal experience of this space.

Though I spoke decent English by this point, most of the childhood media I consumed was still in my native tongue of Russian. Back then, it created some awkward situations (like being invited to a Britney Spears-themed birthday party and asking: “What’s a britty-spee?”). In adulthood, however, it means I’ve been able to retain a very real connection to my heritage, as well as jobs in translation and a wider vocabulary of cultural references.

In my teenage years, having an Eastern European background meant courting communism, espionage, and Putin jokes (which have never been funny, but are even less so now). I used this to my social advantage when needed, but it pained me—still does—that many people in the West weren’t open to the nuances of Soviet culture. In particular, I often rave about Soviet comedies; they are warm, irreverent, clever, and memorable, and always with stunning soundtracks. Despite censorship and propaganda, the cultural respect commanded by theater and the arts meant that the Soviet film industry was an active fount of creativity.

Nowadays, most of these films can be found on YouTube, and the English subtitles, I must admit, are really pretty good. Some films are easy for Westerners to latch onto and understand, while others are indeed too full of cultural references to share widely. But I once shared An Ordinary Miracle with a friend of mine from high school—he was a fan of the unusual and the niche, and had always been interested in Russian history. I sent him a link, tried not to oversell the movie too much, and two hours later received a text: “Wow, this explains so much about you.” I prodded further—my vanity couldn’t let go of an opportunity to find out how another person saw me. “Just the weirdness of it all,” is all he said.

Obyknovennoe Chudo—which frankly I’d prefer to translate as “Ordinary Magic” but the official English title is “An Ordinary Miracle”—is a 1954 play by Evgeny Schwartz. Though another film adaptation was made in 1964, the 1979 version I discuss here is considered the classic.

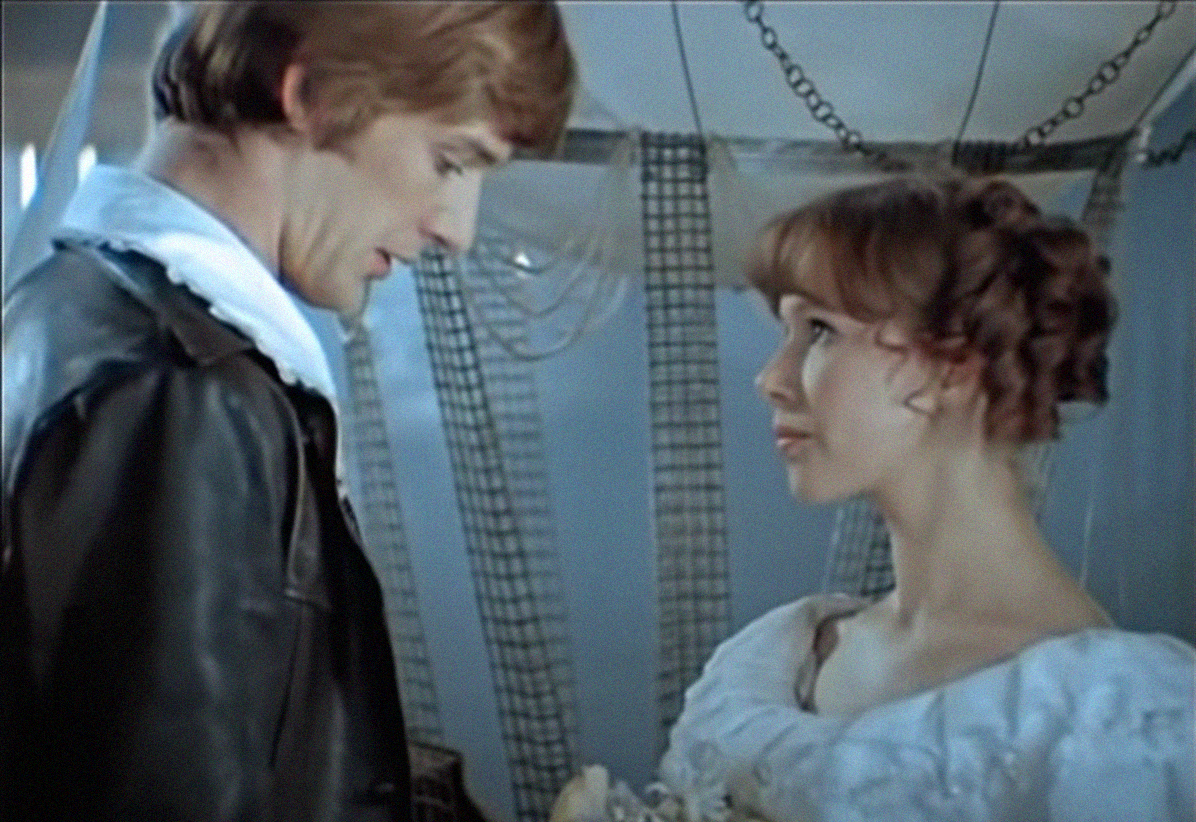

The aesthetics cannot be nailed down: It is at once rustic and palatial, pastoral and professorial, Wild West and esoterica. The basic plot—if you can call it that—is that a Wizard comes up with a fairytale, ostensibly to entertain his wife and battle the ennui that pours out of his piercing gaze. And then the fairy tale characters come to visit. First, the Bear arrives on a speeding horse; a cowboy with long hair and sad eyes. The Bear is no nickname; the Wizard turned a real bear into a man, cursed to revert to bear form upon the first kiss from a princess who loves him. The Wizard finds this backwards fairytale entertaining, but his wife feels nothing but pity for the Bear, not to mention the eventual princess who will have the man she loves turn into a monster and run away (“That’s not uncommon,” replies the Wizard to this concern).

To get the action started, the Wizard casts a spell to entice a King’s passing convoy to stop at their home. We meet the King, a jolly figure undercut by his insistence that he’s a tyrant and a horrible guest, which he proves by occasionally throwing random objects at his courtiers. He is accompanied by a collection of fops; his handsome first minister (who blatantly hits on the Wizard’s wife until he finds out that her husband is a man of magic); a diva lady-in-waiting who wears a ridiculous hat, smokes a pipe, and decries the lack of decent showers; and the Princess—impossibly cute, slightly ditzy, but with a solid rebellious streak.

To get the action started, the Wizard casts a spell to entice a King’s passing convoy to stop at their home. We meet the King, a jolly figure undercut by his insistence that he’s a tyrant and a horrible guest, which he proves by occasionally throwing random objects at his courtiers. He is accompanied by a collection of fops; his handsome first minister (who blatantly hits on the Wizard’s wife until he finds out that her husband is a man of magic); a diva lady-in-waiting who wears a ridiculous hat, smokes a pipe, and decries the lack of decent showers; and the Princess—impossibly cute, slightly ditzy, but with a solid rebellious streak.

With the Wizard pulling the strings, the Princess meets the Bear. She doesn’t tell him that she’s a princess, and inevitably, they fall in love, all while talking and roaming through the Wizard’s house, his dreamscape—coyly posing at each other from behind picture-frames, suggestively making eye-contact through mirrors, sensually intertwining their fingers among hanging plants. But when the Bear discovers her true identity, in order not to fulfill the curse and be forced to betray his love, the Bear departs. She follows him, furious at what she deems his rejection. Dressed as a boy to conceal her identity, she eventually finds him at a rural inn. He doesn’t recognize her—she is no longer wide-eyed and pouty, but braggart and aggressive. And when she starts bad-mouthing the Princess in order to bait him into revealing his true feelings, he challenges the boy-Princess to a duel.

With the Wizard pulling the strings, the Princess meets the Bear. She doesn’t tell him that she’s a princess, and inevitably, they fall in love, all while talking and roaming through the Wizard’s house, his dreamscape—coyly posing at each other from behind picture-frames, suggestively making eye-contact through mirrors, sensually intertwining their fingers among hanging plants. But when the Bear discovers her true identity, in order not to fulfill the curse and be forced to betray his love, the Bear departs. She follows him, furious at what she deems his rejection. Dressed as a boy to conceal her identity, she eventually finds him at a rural inn. He doesn’t recognize her—she is no longer wide-eyed and pouty, but braggart and aggressive. And when she starts bad-mouthing the Princess in order to bait him into revealing his true feelings, he challenges the boy-Princess to a duel.

It’s during the duel that he recognizes her and is distraught; her expression changes back to the feminine, albeit still stubborn and venomous, and she tells him that she never had any intention of kissing him or falling in love with him, that he hurt her so badly by leaving that she will take revenge on him no matter what. He still still doesn’t tell her about the curse, and she runs off. The Wizard—who has suddenly appeared at the inn…out of nosiness? jealousy?—calls the Bear a coward. He says he should have kissed the Princess despite the consequences. Sad stories, after all, have more to teach us than happy endings. Happy endings are for children—says the man obsessed with fairytales.

Most Soviet movies are in two episodic parts, and here ends the first one. To close, the Bear and the Wizard stare at each other for minutes on end. We watch the Bear’s expression shift from despair to rage. He lifts a gun towards the Wizard—his creator, mentor, and tormentor—then slowly moves it to his own head, caressing his own hair with it in a mirror image of how the Wizard had caressed him earlier in the film, before dropping it and sitting himself down in front of a bullseye in total resignation. There is nowhere else for us to look; we must simply watch him process his impossible position. Do we pity him? Or do we judge him? Are we watching through the eyes of the Wizard, or our own?

At the start of the next episode, the Bear tells the Hunter, another guest at the inn, that if for any reason he does transform back into a bear, the Hunter must find him and shoot him. Then the Princess appears and—vindictiveness and hurt emanating from her every pore—announces that she will marry the next man she sees, who turns out to be the smarmy first minister. The Bear, in retaliation, grabs one of the ladies-in-waiting and proposes to her on the spot. “It’s dangerous to get too close to a couple in love,” says the innkeeper, as we watch this train-wreck of back-and-forth near farcical revenge.

At the start of the next episode, the Bear tells the Hunter, another guest at the inn, that if for any reason he does transform back into a bear, the Hunter must find him and shoot him. Then the Princess appears and—vindictiveness and hurt emanating from her every pore—announces that she will marry the next man she sees, who turns out to be the smarmy first minister. The Bear, in retaliation, grabs one of the ladies-in-waiting and proposes to her on the spot. “It’s dangerous to get too close to a couple in love,” says the innkeeper, as we watch this train-wreck of back-and-forth near farcical revenge.

The Princess’s wedding ceremony begins, until the Bear commits that most romantic of romantic acts: screaming “no” in the middle of proceedings, rushing to the altar, and demanding to speak to the Princess in private. At last, he admits the curse. An ethereal hush falls over the conversation. He explains the situation in short sentences, which she quietly repeats as they circle each other, their eye contact unbreakable. The set morphs, somehow, from the inn to a forest. With the truth finally out, and back at the inn, the Bear and the Princess part ways. She falls distraught into her father’s arms, vowing she could never hurt her true love by turning him into a Bear. The royal convoy departs.

A year later, the Bear is roaming the land and the Princess is miserable, near death. The Bear comes to see her, their love still burning strong but tragic. Unable to hold back any longer, he kisses her, and we see the Hunter poised with his gun, ready to kill the animal about to appear. But then…nothing happens. The Bear remains a man, together with the woman he loves. Everyone is shocked, but the Wizard shrugs it off; it’s just a simple miracle. Nothing to write home about. It happens. The entire cast leaves his home in a procession and the camera zooms out to show the house as a theater set, suddenly in flames all around him. He is alone again.

As the viewer, you feel dizzy: inspired, entertained, terrified. You pity each character in turn, love and hate all of them. There is no good or bad, no difference here at all between imagination and reality. Many scenes in the film include characters just looking at each other, or the viewer, during musical interludes. It gives the impression that there is so much they want to say that is simply ineffable. Are any of the characters who they say they are? Who is really pulling the strings? Is the true farce the very concept of free will? And all throughout, there is this underlying sexuality, a pervasive question about how love and obsession alter our worlds, a deeply uneasy tension between control and trust, a firm belief in humor and entertainment as human values, and a serious warning of the dangers of such a life. When the Wizard is left alone in the rubble of his creation, one can’t help but wonder: Who do we do anything for, really? Why do we do anything at all? Are our lives simply fairy tales with unsatisfying endings? And are we telling these tales, or living out somebody else’s imagination?

Last winter, my husband and I visited my mom for the first time since before the pandemic. We’d been having some issues, but this trip felt like a honeymoon. Away from the complications of our regular lives, we were able to re-focus on each other in a whole new way. I wanted to show him this movie; I wanted him to once again see me as the creative, unusual, eclectic, light-hearted, thought-provoking person he fell in love with.

I talked about it for weeks, checking the weather for the perfect rainy day vibe, explaining to him why it’s so important to me, trying to prep him for the acid trip of the experience, telling him the story of how I watched it once a week in childhood and how it was the first time someone said to me “this explains a lot about you” and made me feel so seen. I wanted him to see the way this movie had embedded itself into my psyche from all those childhood afternoons in the creepy studio. My kinks, my interests in trust and control—where else could they have come from but the brooding yet cheeky figure of the Wizard? His wife was a blueprint for the care and poise I wanted to emulate as a partner. Throughout the film, the Wizard talks about how everything he does is for his wife—that he’s in love with her “like a schoolboy.” When his fairytale goes sideways, he’s tickled until he sees her tears, and then it’s all ruined for him. I wanted to be loved like that.

In feeling my husband’s distancing from me, I had become a nagging, nervous, needy version of myself. When we first met, he said I was the most fascinating person he’d ever known—and I wanted Ordinary Miracle to remind him of that first impression, to remind us both to remain interested in each other. The goofiness of the tyrant King, the ditziness of the Princess, the sexual confidence of the first minister, the subtle queerness of the Bear—just a little bit of attention would show that I had incorporated bits and pieces of all these characters deeply into myself. I had truly incorporated the “weirdness of it all.”

On the day we finally sat down to watch, I had to ask him to put his phone away and pay attention multiple times. Though I understand it’s not easy to watch a movie in another language (and his first language isn’t English either, but I couldn’t vouch for the quality of any other subtitles), especially while being embedded in my family and our multiple languages for an extended holiday, this felt endemic to all the problems we’d been having. I had started to feel like I had to beg for his attention. We fought about it, I explained, he understood, apologized, and worked to repair it. But six months later, we broke up.

When we did, there were plenty of conversations that eventually and increasingly fell into silence. There was just so much to express—the disappointment, the hurt, the hope for our individual futures—but nothing felt like enough. If only we’d had the Ordinary Miracle soundtrack to make it all the more poetic, to fill the silence, to add meaning when our expression failed. Turns out you really can’t ever truly know another human being. Some things just can’t be said out loud.