Text me when you're done: Autobiography of Red

Weakness is not shame. Naomi Gordon-Loebl makes a case for Anne Carson’s retelling of Hercules as queer manic pixie dream boy.

It was a bisexual poet I worked with at a restaurant in college who first introduced me to Anne Carson’s Autobiography of Red. We were all standing on the patio of the restaurant after my first shift, smoking cigarettes and trading stories about the night. She looked right at me.

“You must be so bored,” she said, and instantly I knew what she meant—not bored on the patio, but bored in my life, my existence as a somewhat lost 19-year-old bussing tables in a Midwestern college town. It was, to borrow a line from the book, “one of those moments / that is the opposite of blindness.” The poet brought a copy of Autobiography of Red to our next shift. On the title page she’d written, “dear n, you need this book.”

I inhaled it, which was an odd choice—like most of Carson’s work, it’s dense, and reading fast means you risk missing things. But maybe the poet was right: something in me had needed it, and I couldn’t wait another minute. What had she seen in me on that patio, bantering about regulars who drink too much and professors who don’t know how to tip? How had this stranger seen past my hiding to know exactly where I was—or where I needed to go?

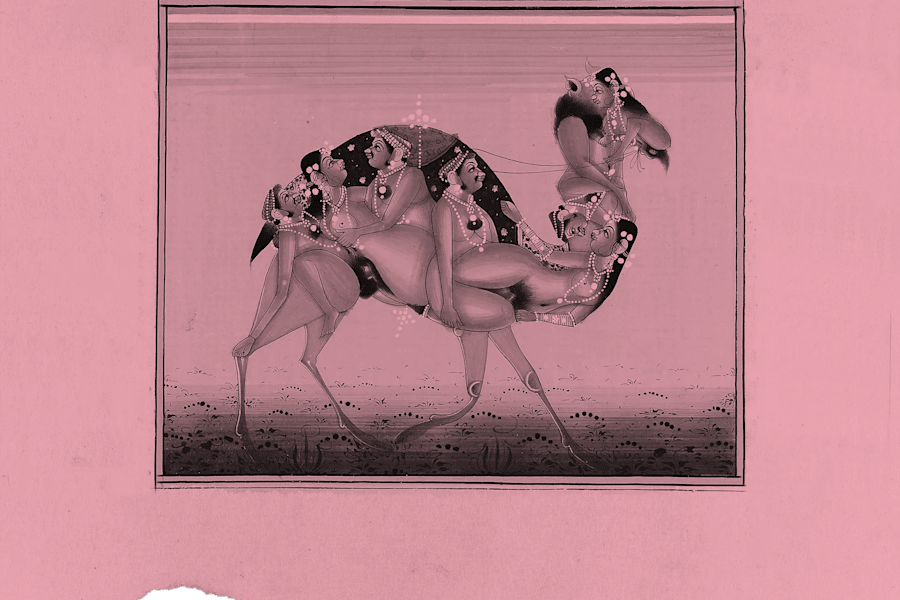

In theory, Autobiography of Red is a retelling of an obscure episode in the ancient Greek myth of Herakles (better known in Western culture by his Roman name, Hercules). Among Herakles’ twelve labors are to visit the island of Erytheia, where he must slay the giant Geryon and his herd of cattle. Descriptions of Geryon vary—he is multi-headed, multi-bodied, sometimes in possession of an enormous set of red wings. In all tellings, he is both monstrous and inconsequential, merely a killing on Herakles’ to-do list.

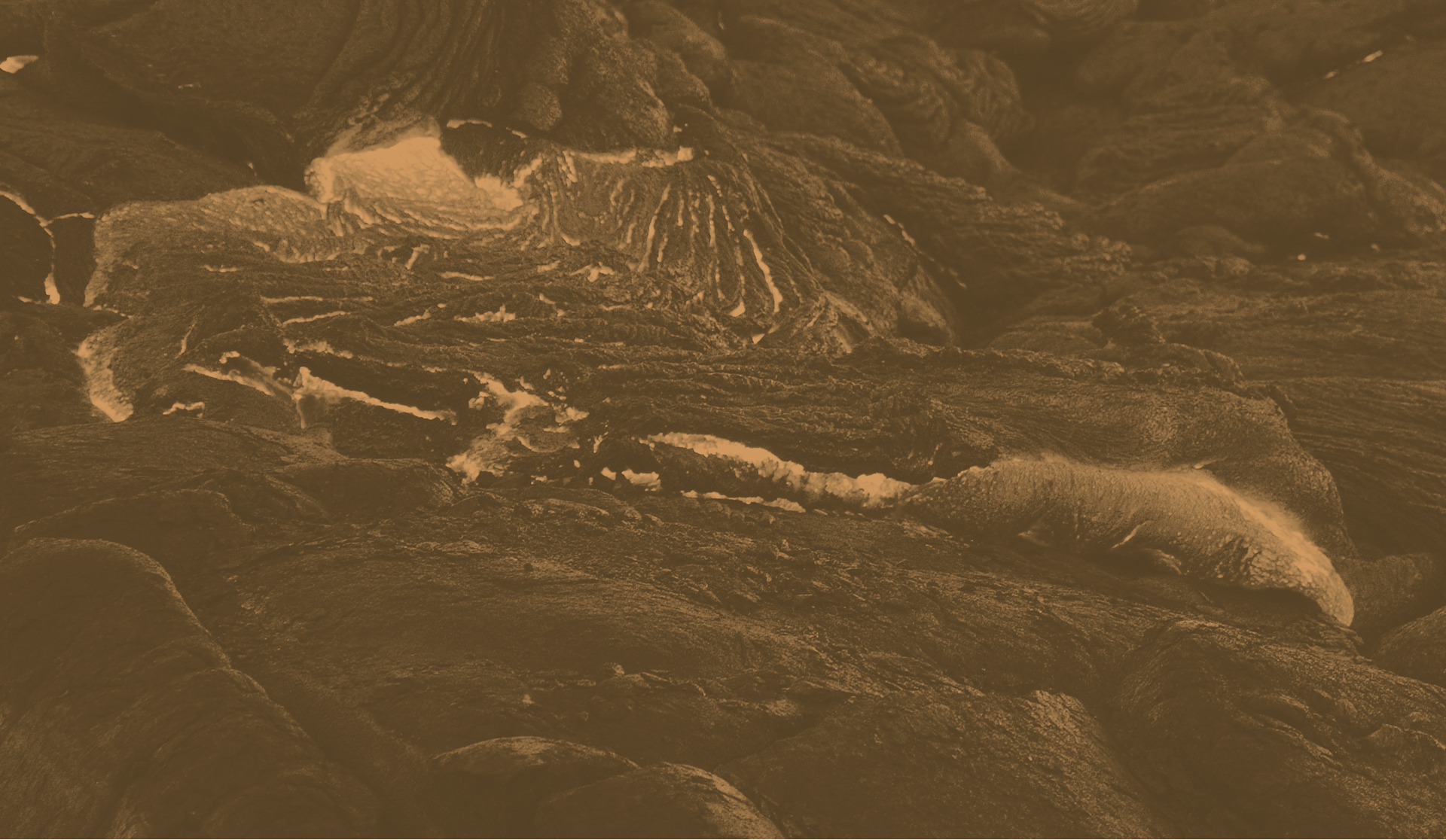

Autobiography of Red takes on this story of Herakles and Geryon. But in Carson’s version, Geryon is a queer teenager with a shitty home life. He falls in love with a manic pixie dream boy, Herakles, who inevitably destroys his heart. Also: Geryon is a red-winged monster. Also the whole book is a novel told in verse. Also it’s sort of Geryon’s autobiography, told in the third person. Also, they visit several volcanoes (at least one handjob occurs en route). It’s a far cry from the original myth—but somehow, it’s exactly right.

#

At this point, I’ve lost track of how many copies of Autobiography I’ve given away. I gave it to a friend, whose assessment was that it was beautiful but perhaps “too smart” for him. I gave it to a girlfriend and wrote her name on the inside cover, my own version of an inscription—this story is yours, I wanted to say—but then hated the way I’d written it, so I bought her another copy and kept the inscribed one for myself. What’s one more Autobiography on my shelf? In fact, I lent out the original from the bisexual poet years ago and never got it back. I’ve found that it’s never a bad thing to have an extra copy of Autobiography on hand.

I would’ve bought it for a new lover, but I spotted it on her desk one morning while we were sitting up in bed, drinking coffee naked.

“Is that… Autobiography of Red?” I asked. It’s not the most common book. A little different from seeing Sally Rooney on the bookshelf of a 30-something-year-old who likes to read.

Of course, she said. She’s obsessed with it. She’s read it so many times. She’s given copies to so many friends.

“… Marry me?” I said.

I didn’t say that, actually, but I did stare at her, a little shocked. “Not touching / but joined in astonishment as two cuts lie parallel in the same flesh.”

#

Sometimes I feel like a character from a book from the early 2000s self-help aisle at Barnes and Noble or an AI-generated version of a gay millennial on the couch when I talk about my self-loathing. Even with all of my anxiety-fueled insomnia, I could put myself to sleep. Blah-blah, I grew up thinking I could never be desirable (“Geryon was a monster… ”). Blah-blah, I still have a hard time believing that the things I hate about myself are the very things that partners find attractive (“... everything about him was red”).

It’s easier, isn’t it—or at least more flattering—to imagine ourselves as the protagonist of some weird artsy book that bisexuals and poets and bisexual poets gift back and forth in their courtship rituals. My favorite line in Autobiography of Red might be: “This would be hard for you if you were weak / but you’re not weak, his mother said / and neatened his little red wings / and pushed him / out the door.” A surface-level read of this line—especially out of context, as in this essay—suggests wise care on the part of the mother. Aw, so sweet: she’s reminding her tough son, as he goes off to school, that he is resilient. He can handle anything—the bullies, the abusers, the mythological Greek hero who’s been sent to slaughter him. But what hurts about the line is that it is hard for Geryon—whether he’s weak or not is irrelevant.

Weakness, as it turns out (and as the best versions of queer love teach us) is not the mark of shame we were raised to believe it to be. So what if we’re weak! So what if we’re sissies; so what if we cry? The brutality of the line is that Geryon worships his mother; at this point in the book, she is his closest ally. And yet even the person he feels most at-home with is unable to see him; instead, she tells him he’s strong and pushes him out the door. When I read that line—as I do, over and over again, rereading Autobiography of Red, buying copies of it for new lovers, sending pictures of pages to friends—I feel tender toward Geryon and those supposedly monstrous wings of his. I feel moved by his resoluteness, the way his emotions startle and overtake him, his inability to be anything other than a complete and utter weirdo. Which is easier, as it turns out, than feeling tenderness for myself.

I was walking with my own mother in Prospect Park last year, trying to explain what I love about Autobiography of Red, when I saw in my peripheral vision someone I’d ended a relationship with a month earlier (I never did get to give her a copy). It had been a particularly painful breakup—it always is, in my experience, when neither of you can quite put your finger on why something is ending—but I couldn’t stop myself from saying hello. Everything about the interaction felt sad and a little on the nose; the November cold, the bare trees, the way we lingered too long on election small talk because neither of us wanted to walk away.

After we finally did, I told my mother about one of my favorite lines from Autobiography of Red, when Herakles calls Geryon’s house for the first time after they break up. It’s the best description I’ve ever read of the particular pain of hearing from an ex-lover out of the blue: “Herakles’ voice went bouncing through Geryon on hot gold springs.” I cried, just a little, on the walk home from the park. I considered texting the line to my ex. I knew she would understand. But when I got home, I opened the book and was reminded of something that is easy for me, a romantic, to forget: Autobiography of Red is a book about love and heartbreak, but it’s also about what happens next. Soon after that phone call, Herakles and Geryon travel to the volcano pictured on the cover—as friends. The section opens with an epigraph: “Sometimes a journey makes itself necessary.” Sometimes a reread does, too.