Text me when you’re done: Love Always

Karim Kazemi on the exquisite melodrama of a 1985 Ann Beattie novel.

If you had been the kind of person to spend all day at home with the TV turned on to keep you company in the year 1983—which is to say a woman of a certain place, age, race, class—then you might’ve been thrilled to be visited by the actor Anthony Geary twice on one Tuesday. As Luke Spencer, the picaresque nightclub owner on ABC’s General Hospital, he would appear in the afternoon, donning a familiar guise. At night, he would reappear as a young physician whose summer assignment to the Hamptons-esque resort town of Paradise Isle takes a lurid turn when he uncovers a silent epidemic of genital herpes, in the made-for-TV movie Intimate Agony.

He’d expected to spend his days tending to jet ski accidents, but he finds himself on a crusade against contagion instead. He falls for a local woman. She has herpes, and so she rebuffs him. Since she caught it, she confesses, she won’t let anybody get close. A real estate developer schemes to conceal the outbreak to protect his business interests. He has herpes. He gives it to his wife. Their 16-year-old daughter is pregnant. She, too, has herpes, which causes her to give birth prematurely, passing the infection to the baby, briefly, before it dies.

Perhaps the thrill of a familiar face is no match for such mixed messaging. If you were the kind of person who believed that soap operas contain oblique instructions for how to live your life—which is to say, let's be honest, a middle-class white woman in the middle of America, in the middle of her life—it also might have been a little bit confusing to witness Geary’s familiar figure inhabit a narrative that is General Hospital’s exact moral inverse, where lovemaking brings beautiful people blisters, instead of back from the brink.

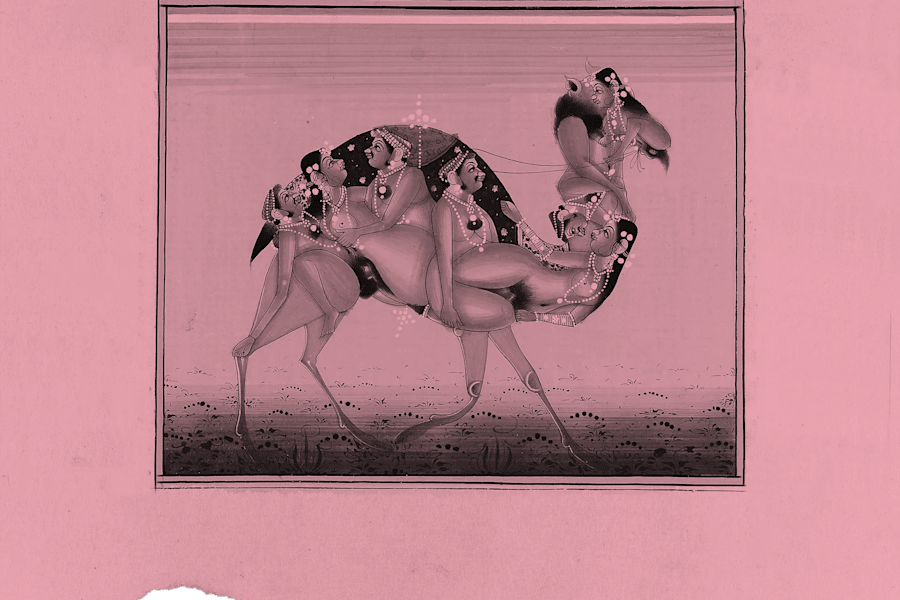

It also must have been, probably, what Ann Beattie was riffing on in her 1985 novel Love Always, in which the sulking teenage star of a daytime hospital drama called Passionate Intensity is sent to live with her aunt named Lucy Spenser, the winsome it-girl advice columnist around whom the novel’s action swirls.

After toiling away their twenties in New York City, Lucy and her friends, a close-knit cadre of media people, have stepped off the treadmill entirely, decamping to rural Vermont to lend the absolute bare minimum of their talents to a countercultural magazine called Country Daze. Dislocated as they are from the national action, their analytical faculties have been dampened by years of leisure. That it is “proof-positive that the entire country was coked-out” is the closest they come to mustering a cogent accounting of the magazine’s runaway success. “Making up the questions and writing the answer on pieces of pink stationary,” Lucy becomes Cindi Coeur, “a Latter-Day Miss Lonelyhearts” whose stilted, reality-immune ministrations are the magazine’s standout offering.

In the mid-1970s, Beattie’s short fiction began to appear with regularity in The New Yorker. These early stories of white, college-educated professionals spinning their wheels, stuck at one or another amorous impasse, were rendered in prose so uninflected, so coolly declarative, that, reading them, one sometimes gets the sense that Beattie’s narrator is observing them from a million miles away. Across her oeuvre, it’s difficult to discern if Beattie wants readers to care for her characters, or if they are to be held in deep contempt. Or do they deserve our pity, that difficult synthesis of both? (Presumably as a savvy tax maneuver, the copyright to several of Beattie’s books from the 1980s is held by an entity called Irony and Pity Inc.)

While some critics were quick to dismiss her entire fictional enterprise as a cheap trick, even they couldn’t deny Beattie a certain measure of cautious regard. She was, they wagered, a crucial interpreter of the inscrutable whims of the Baby Boomer generation, and her output was tracked with the kind of attention that a healthy society might bestow upon social scientists.

The novel is, if only superficially, a satire of consumer culture among the 1980s creative class. Having escaped both “Madison Avenue and the system in general,” Beattie’s crew of lapsed high-achievers traipse around town in jelly sandals and in something called Shakti sandals. They spike their protein smoothies with Perrier, order crab-stuffed avocados at lunch, and calisthenics is the closest thing any of them have to a religion. They invest. Lucy gives Hildon, her lover, and the magazine’s married editor-in-chief, a waterproof watch “that would tell him,” she thinks, “even as he fell into the ocean, what time it was in Cairo.” Hildon’s wife Maureen suffers a miscarriage while "on the phone, ordering a set of glasses from the Horchow Collection.” In an attempt to regain psychic equilibrium, she forms a feminist guerrilla cell with her former psychotherapist, holding a women’s vintage clothing boutique hostage on the demand that they “stock useful things for the contemporary woman, such as thermal underwear, body-building devices, hiking boots, and Mace.”

“It’s a particular group of people,” said Beattie, in a New York Times profile occasioned by the novel’s publication, when asked to reflect on whether the itinerant, untethered lives depicted in her fiction are characteristic of society as a whole. “I don’t think the whole nation is out there in their wagons simply crisscrossing the Interstates.”

For decades, journalists have attempted to coax Beattie into issuing sweeping proclamations on civilization’s present stage, and she has demurred with commendable grace. On rare occasions, she has pretended to humor them. The results are impressions so tepid and equivocal that their effect is ultimately comic: “There has—coincidentally, maybe—among my friends, been a lot of mobility,” she told another interviewer in 1990, “and it’s had pluses and minuses.”

Like an expert witness meticulously choosing her words to avoid committing perjury, Beattie downshifts into a discussion of her own experience of reality when she is forced to play oracle. She speaks in the same voice—evasive and laced with insinuation—in which Lucy dispenses her counsel as Cindi Coeur. “Many times problems go undetected because of the frantic pace of our world, which we have come to accept as normal,” she instructs one of her imaginary solicitors. “Have your fiancé checked for pinworms.”

Like any good fiction writer, the predicaments described in Lucy’s column are not pure inventions, but quirked-up, thinly hyperbolized anagrams of real incidents that have occurred, and continue to, in her milieu. (In one fictional submission, a woman complains that her husband insists on stashing cash beneath the pillow and “plunging his hands into the money” while they make love. Later, when Hildon sleeps with Country Daze’s secretary, a rumor circulates that she had left her headphones on, “listening to a tape of the Jerry Lewis telethon,” during the act.) Lucy’s column is a bitter, cynical mockery of a media industry that thrives on readers’ thirst for intimate expertise. Revenge from a writer whose polite ironies were, at times, brutally misappropriated as actionable advice.

“I’ve had people write to me,” Beattie recalls in a 2011 interview in The Paris Review, “‘I read your story and suddenly it all came clear to me and I’ve left my husband and I’m in a downtown Cheyenne, Wyoming motel, and what do I do next?” At readings, they show her the insides of their wallets, displaying a paragraph they have snipped out of one of her stories “where they used to have pictures of their husband and children.” If this is praise, it's of a kind that's best suited to a culture warrior, which Beattie decidedly is not. For a writer of fiction as allegedly crisp and indifferent as Beattie’s, it must be unsettling to learn that it has given some people permission to renounce romance and blow up their lives.

Much like Beattie’s extreme devotees, the characters in Love Always have gotten the news that heterosexuality is canceled and over, a thing of the past. “That’s a good thing about heterosexuals—that they stick together,” says Noonan, a gay guy seasonal allergy sufferer, momentarily praising the practice, but only because he thinks that his thing is worse. “Fags move on like flies when they smell meat.”

In her columns, Lucy invokes a chorus of lovers who have knocked sex and romance from their pedestals, only to smuggle them around now like contraband, incapable of throwing them away. They cry out for her to confirm their suspicions that it’s really bad, whatever peculiar, bewildering circumstance they have gotten themselves into by loving, or merely fooling around with, somebody else.

When I was a literal teenager, my brain and body flush with urges that I didn’t have a handle on, if only because they were brand new, I did something ridiculous: calling the contact listed on the webpage for a local chapter of Sex and Love Addicts Anonymous. “It doesn’t matter how much stuff you do,” said the kind man who answered. “What matters is if doing stuff causes you distress.”

What happens when knowing that something is unhealthy or unfashionable isn’t enough to keep you from hurtling after it? Styles of irony and cultivated nonchalance (like Beattie’s) tend to flourish in this breach. One strategy for taking the sting off your cognitive dissonance is choosing to downplay your true desires, a.k.a “playing it cool,” a.k.a. kissing with tongue firmly planted in cheek.

These days, when people feel bad about watching and enjoying a certain TV show, because its plot is preposterous or sentimental or the actors are acting too hard, they apologize by calling it “soapy,” which strikes me as a real waste. (There’s a word for what they’re describing that already exists: “melodramatic.”) Even more importantly, as a narrative medium, what really distinguishes soap operas is not that they are debased and unserious, but their longevity. They have survived, amid the shock social upheavals of the 20th century’s second half, by diligently refitting their storylines to viewers’ shifting beliefs about what is right. General Hospital, for example, is older than the Big Mac.

Guilty pleasures last a long time.