Text me when you're done: The desires of Louise Labé

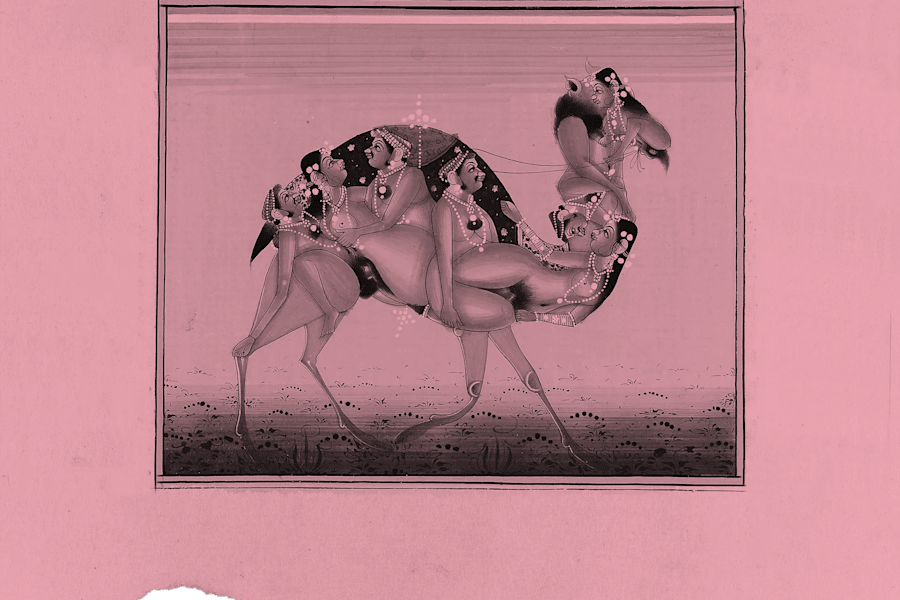

Ami Xherro on the feminist Renaissance poet who made love into her equal.

[Such Endless Waiting], an elegy by the feminist Renaissance poet Louise Labé who reversed the gender of wanting, ends:

MY LOVE, I BURNED FOR YOU UNTIL DESIRE CONSUMED MY BODY. THEN THE FLAMES GREW HIGHER. I’M STILL BURNING UNDER THE ASHES OF THIS PYRE. ONLY YOUR TEARS CAN EVER QUENCH THE FIRE.

Louise Labé’s poetry–twenty-five sonnets and three elegies–lassoes the drama of an ancient feeling past the precipice of desire and into a frenzied, startlingly contemporary love. What is real expounds a delicious dream, a dream drenched with everyday longing and the insatiability of days. What, other than poetry, can be the backdrop of love? What can suffice to bed such cavernous desire, as a canvas for such need?

Labé’s achingly erotic verses and thinly veiled confessions rewrite the male-dominant traditions into the vantage point of a feminine subject. It is the thematic of a love of equals that makes her poetry all the more potent. For what may have been the first time, a French Renaissance audience heard the force of a woman’s love, whose influence outlived Labé by centuries.

Yet her very existence was and continues to be highly debated. In 2006, French academic Mireille Huchon authored a book in which she denounces Labé as an elaborate hoax manufactured by a group of male poets amidst the “poetic frenzy” of 16th-century Lyon. She notes that given the lack of autobiographical details compounded by the fact that Labé’s oeuvre was essentially ignored for two centuries, Labé remains an enigma: was she a new Sappho or a courtesan posing as an author?

Whether or not Huchon’s thesis is true, this mystification of the feminine poetic voice suggests a deep discomfort with a tradition of life-writing: writing as constitutive and not merely representative, and love as a palpable condition and not a higher ideal. Though largely overlooked in her time, Labé’s spirit is felt in the poetry of Edna St. Vincent Millay, Emily Dickinson, Forugh Farrokhzad, Ariana Reines, to name a few.

My own fascination with Labé rests in the act of writing as a construction of life and of a persona willed by the myth of the written word. So what if Labé is a hoax, if her writing provokes an awareness so deep that we can reach in and hold it? It would not be the first time a female poet is more famous for her personal life than her work, these categories hardly dissembled in the work of love.

Labé stopped writing at 28. Wedded to a man almost 30 years her senior, she opted instead for the obscurity of life in a rural village. Such an exit only serves to underscore the price of her passions, having received her fair share of criticism and dismissal from male contemporaries. Left with mere reminiscences of her near-forgotten amours, we can only but complete it with our own:

Ah laugh, ah forehead, hair, arm, hand, and finger,

ah plaintive lute, viola, bow, and singer —

so many flames to engulf one single woman!

I despair of you; you carry so many fires

to touch my secret places and desires,

but not one spark flies back, to make you human.

The dialectic of desire and its quenching is the emblem of literary love. One pines and one fulfills. One hungers while the other feeds. One writes what the other reads. The act of writing is the basis of pleasure through which meaning is infinitely deferred, edged out of easy comprehension, and cleaving two fundamental human acts: the textual and the sexual. Consider how easy it is to say, “I want you” by not saying it, or the significance of a crisp “I do”.

The root of romance is blind faith; a confidence in the unknown, or the unknowable; in the consummation of an imaginary future, in the reciprocity of saying the unsayable. What is more absurd than the idea of falling without knowing if there’s anything to it? Or, to reverse the proposition, what is more unbelievable than the dream of some earthly union in which lover and lover embrace in symmetrical desire?

The spark that flies back; the fires of secret places; the engulfing flames of one woman—these are the kernels of love, the infinite beginnings of any relationship. In every beginning is possibility: the tempting blink, the rolled-up sleeve revealing the beaten vein, the near-silent sigh, the jutted laugh. Each flame begins with a question of its end, and in ending, of its beginning over and over again. This poem begins, like the love affair, with the possibility of its passing. What is love but a deferral of the end? And the end but a love fulfilled?

In a long history of women writing about love, from Enheduanna’s hymns to Ishtar to Sappho’s lesbic lyric to Forugh Farrokhzad’s unmitigated pleas, is evidenced this: feminine desire is a life-giving force, grounding heaven on earth and bringing intense suffering together with an acute understanding of the self. To understand oneself is to open up to the beyond.

To tell the story of a life, Virginia Woolf writes, “the autobiographer must devise some means by which the two levels of existence can be recorded–the rapid passage of events and actions; the slow opening up of a single and solemn moment of concentrated emotion.” To write “I” is no simple task. To write “I” is to channel the amorous frenzy of the desire for a “you”, confounding both into the rimless source of love.

So when Labé writes,

I am wounded. I ask you only to kill the pain,

But not to extinguish the burning I crave to feel,

This desire whose broken life would break my own.

How should we respond?

To respond is to be already bound.

Labé’s poetry, and perhaps poetry in general, is a litmus test for desire and the extremes it inhabits. If poetry is a form of thought and not knowledge, and love is an experience rather than a fact, then the experience of reading poetry is already a courtship. Every “you” resounds with “I”, the two perfectly teasing out the insecurities of the other which makes desiring itself an aphrodisiac. There is no other fact but that of suggestion and suggestion can be found everywhere: in the delay of the response; the shadow of the hum, the crumb on the thumb.

Shakespeare would say:

But ah! thought kills me that I am not thought—

(Sonnet XLIV)

Think only of Francesca da Rimini and her brother-in-law Paolo who embraced over the pages of a book and were sentenced to an eternity in hell, or the fatal kiss between a pupil and her tutor in Boccaccio’s Il Filocolo. Who is not thought who can think of oneself? Who can think of oneself without the glimmer of the other?

Love needs tongue. Love needs a language, however unstable, through which it sheds the specificities of its subject. Love needs bodies through which it is triangulated. Love needs a substance which can tolerate refusal to the point of its obliteration. Love needs expression and rearticulation.

Kiss me again, rekiss me, and then kiss

me again, with your richest, most succulent

kiss; then adore me with another kiss, meant

to steam out fourfold the very hottest hiss

from my love-hot coals. Do I hear you moaning? This

is my plan to soothe you: ten more kisses, sent

just for your pleasure.

Poetry is an incantation that withstands uncertainty. Like love, it grows more delectable with doubt. Therein grows a willingness to accept the unknowable parts of another. Trust in the unknown ignites the flame. Do I hear you moaning? or is it the wind? Whoever has loved has imagined a future otherwise—has envisioned a kiss in the hottest hell, the shadiest bower, the plushiest bed—a future built on the sands of possibility.

Of a poet, the greatest honor is to say that she wrote as she lived. As Labé puts it, the greatest pleasure there is, after love, is talking about it.