The forgotten history of Clit Club

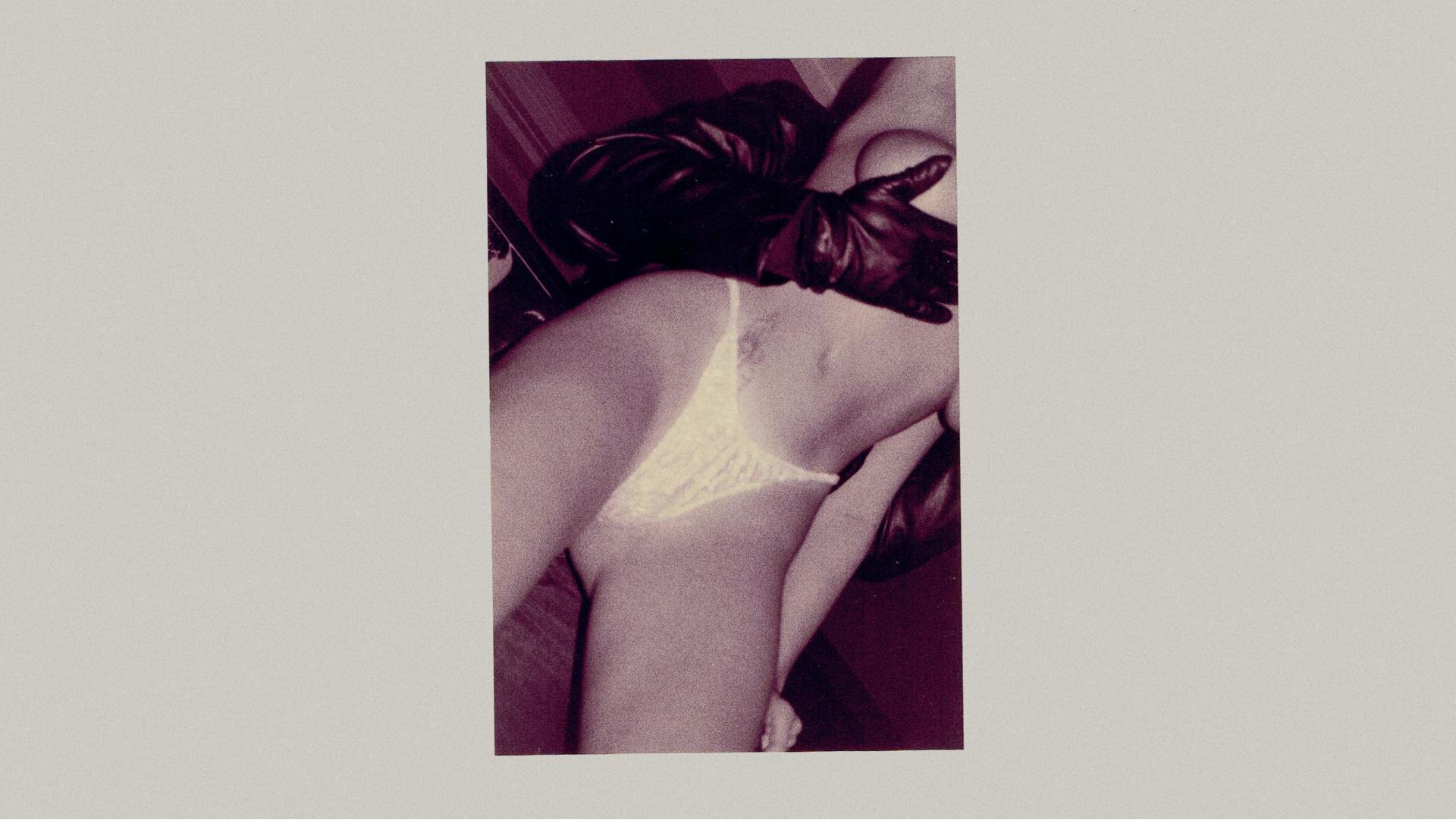

Photography by Alina Wilczynski. Shot at Bar d'O.

“It was total sexual freedom. You just haven’t felt it since.”

Nina Kennedy remembers her first visit to the Clit Club not because of what went on inside but because she never made it past the front door. It’s not what you think (or maybe it is). She was picked up outside, and went right home with a “beautiful woman.” The rest, as the saying goes, is history.

Years after that first night, Kennedy had become a regular. The Clit Club, moreover, had earned a reputation as a place of sexual abandon; one, Nina says, of “total freedom,” where you weren’t breaking any boundaries because “the boundaries were already broken.” This was a place where, for one fabulous night a week, you could go and genuinely leave it all on the dance floor, clothes included. It also happened to be a rare place run by and for a bunch of dykes.

“It was the spot,” Nina says, reminiscing about the heyday of the Clit Club from her apartment in the East Village. “You saw just about everything—women in leather, women in chains, some women being pulled around by collars. The sexual energy was just so high.”

Founded by Julie Tolentino and Jocelyn Taylor in 1990, the Clit Club was a recurring Friday night party in the Meatpacking District of downtown Manhattan, back when it was a truly industrial neighborhood (think decaying piers and meat carcasses) that transformed at sundown into a no-holds-barred, anything-goes terrain of sexual abandon. There were topless dancers; hot bartenders; good music; great sex. From the beginning of the decade until 1999 (and, resurfacing in other downtown neighborhoods until 2002), the Clit Club reigned. Perhaps it’s hard to imagine such a raunchy, women-led space surviving in the year 2023, but that’s exactly why the Clit Club is worth revisiting in our current moment—a moment when so many lesbian bars have closed, and yet, more continue to open.

–

At the height of Clit Club’s popularity, old liberatory sentiments of the 1970s were being eclipsed elsewhere in the United States, replaced by assimilationist politics and the (still ongoing) battle for legal rights. But as mainstream gay culture became increasingly commodified, the Clit Club was only getting more and more radical. Nina remembers her first spoken word performance, which happened mid-decade at the Club: trained as a classical musician, she delivered the poetry as if “building toward a climax,” an erotic dancer accompanying her words.

“The dancer interpreted the words, and there was no music, so we were just making it up as we went,” she says. “It got to the point where, by the end of the reading, the women were just screaming, just to release some energy. I’ll never forget that first performance. We cut the lights and just let the women scream, do whatever they needed to do.”

The power of the Club extended beyond its four walls: after the performance, Nina was approached by a producer, who eventually featured her in a documentary which premiered at the Berlin Film Festival in 1999. The title? Verbal Sex.

Of course, there are caveats to the Clit Club ascension story—points in the timeline where, despite the thrill of the party, real life got in the way. The AIDS crisis, for one, decimated New York City’s queer community. At its height, newly elected mayor Rudy Giuliani pushed through $3.1 million in budget cuts to the city’s AIDS agency, despite repeated protests from groups like ACT UP and Housing Works. Reviving a Prohibition-era “cabaret law” that banned dancing without the proper license, Guiliani cracked down on New York nightlife, effectively crushing it. It was a move reminiscent of the criminalization of gay bars pre-Stonewall, except this time, AIDS loomed large.

“He closed the men’s bathhouses,” Nina remembers, “and we didn’t have topless dancers again at the Clit Club. He just wanted to tamp down on all the sexual energy in the West Village. He would’ve banned it if he could have. But at the same time, we understood it was a health crisis. We needed to do something drastic to save lives, because we lost so many of the boys.”

Years after the permanent closure of the Clit Club, co-founder Tolentino (along with five co-authors) reflected on the Club’s legacy as an “underacknowledged part of the city’s queer history” for an issue of GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. The legendary reputation of the Club is echoed throughout the piece by the 10 interviewees, who describe a place that was equal parts ephemeral and ever-present. Bartender Lola Flash recalled the “mix of people”: “There were so many beauties of all genders wrapped in skins of all colors, especially melanin-filled.” Dez, a door person, said “sexuality was an open book,” and Michele Hill vividly remembered the smell: “Drakkar cologne worn by the butches and the meat meat meat being delivered up and down the street.” Meanwhile, the specter of AIDS always lingered: members of Clit Club “crew” (AKA, the staff) handed out informational pamphlets on HIV, AIDS, and STDs, and talked openly about sexual health.

–

In a kind of last hurrah for the club, Clit Club was “reactivated” for one night only in the summer of 2015 by curators Leeroy Kun Young Kang and Vivian Crockett (both of whom also co-authored the GLQ article with Tolentino). It was a chance to “reflect on the intense labor, love, relations, and creations that came out of years of showing up together publicly and privately, interpersonally and politically,” wrote the pair. Clearly, the lack of division between politics and passion at the Clit Club lived on in queer collective memory. And while that’s certainly part of what made it special, it’s not the whole story. There was no willingness to abandon radicalism in the name of respectability politics; there was also, to be clear, lots and lots of sex. And it was, above all else, a DIY-driven endeavor—as far away from modern day corporate-sponsored Pride parties as you could possibly get. In an era where it kind of feels like everything has become a commodity, the Clit Club remains in a league of its own.

“Nothing compares, really,” Nina says. “That level of public sexuality…you would see women just going at it downstairs. It was total sexual freedom. You just haven’t felt it since.”