State of Dating Volume II: Real Intimacy Through Inclusive Community

Feeld State of Dating Volume 2

Dating is hard. Notice we didn’t say online dating—that’s because in the post-pandemic reality, connecting digitally is no longer limited to dating apps and social media. Our schooling, work, organizing efforts, and more, shifted, at least in part, to digital platforms. So much of our lives happen on our devices that connecting with friends, family, partners, and flings via apps is second nature for some. Yet true intimacy and authentic self-expression require a safer environment, and safer environments are built on transparent, equitable, and inclusive spaces—spaces that prioritize and protect marginalized groups.

As our days are increasingly filled with gig work, zoom meetings, and side hustles, the time we spend connecting with romantic or more intimate interests is a valuable commodity. We need our limited amounts of free time to focus on flourishing and joy—our mental health and well being demand it. Frankly, it can be an exercise in frustration to swipe endlessly if the goal is to meaningfully connect with others. Where is the real, real?

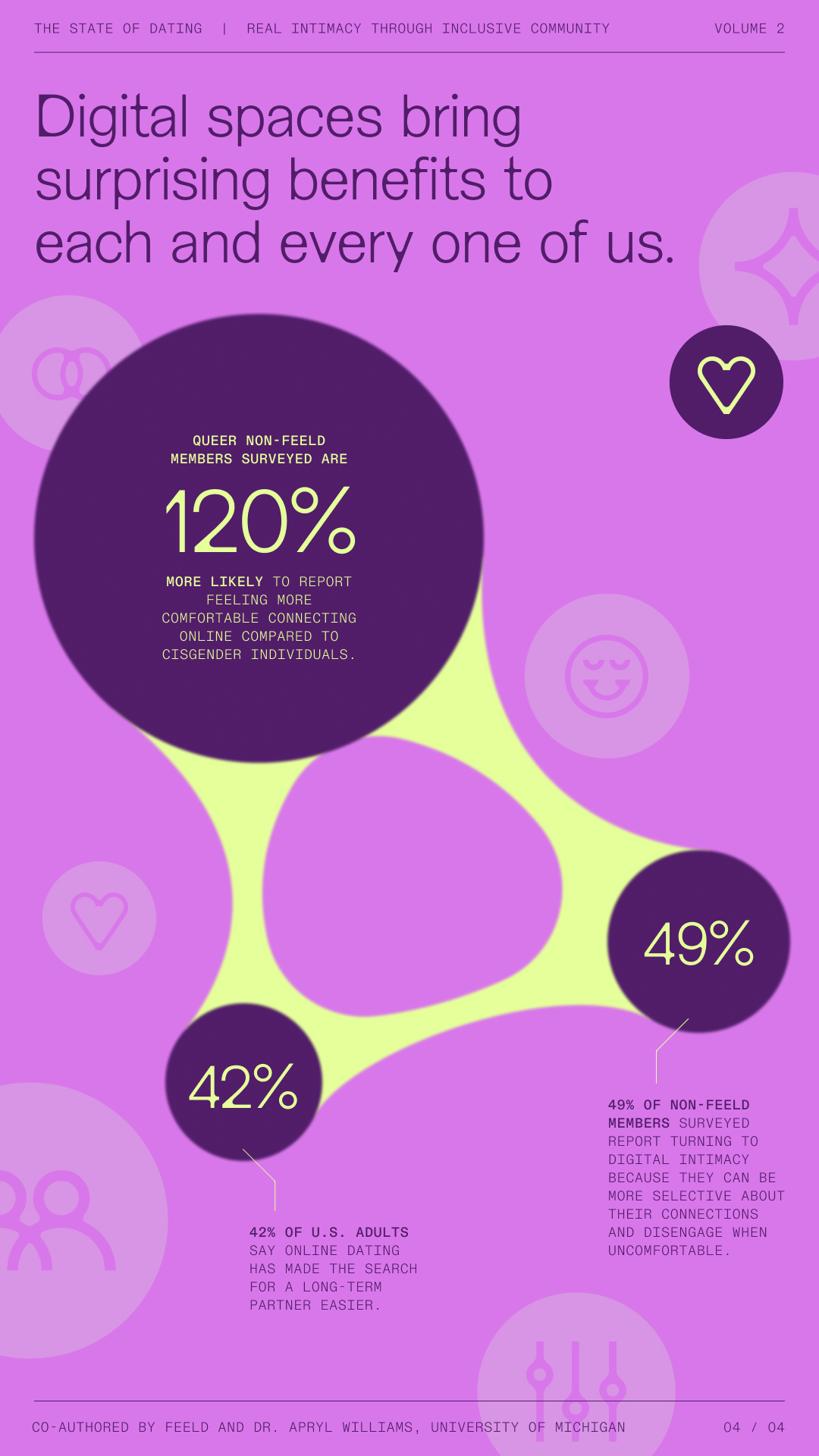

Well, ironically, it’s still online. The proof is in the numbers—42% of U.S. adults say online dating has made the search for a long-term partner easier1, and 61% of LGBTQIA+ dating app users report having positive experiences2. This is consistent with Feeld’s research, where 63% of surveyed Members and nearly 30% of non-Feeld Members met their current partners on Feeld or another dating app3.

For those of us who exist in the margins outside of the mainstream user - arguably the conventionally attractive, cisgender, straight-passing, White person - the spaces that we choose to move in can make or break the dating experience. Sixty-four percent of Feeld Member respondents reported greater openness on Feeld than on other dating sites or in person. Comparatively, 12% of non-Feeld Member respondents said that it can be harder to find common ground quickly in person compared to online, where shared interests are clear. This suggests that when spaces are designed with equitable safety in mind, Members feel more comfortable being real—meaning that they can co-create thriving communities of authenticity and in turn, find the deep connection they are seeking.

While dating platforms present well-known challenges for their mainstream users, they continue to be a tool for connection. The industry opportunity lies in democratizing the dating experiences of marginalized groups in digital spaces by deep diving into the challenges they face in order to improve their interactions and engagement. By creating representation, inclusivity and visibility for these communities, we can champion the characteristics they uniquely bring to the table—authenticity, trustworthiness and intentionality in connections, for them and users at large.

Survey Respondents

We surveyed 2,952 Feeld Members from 65 countries (referred to as Members or Feeld Members)

- United States (51%), United Kingdom (10%), Canada (8%), and the Netherlands (4%).

- 17% identified as male, 55% female, 28% non-binary, trans, or other genders.

- 25% identified as bisexual, 16% pansexual, 15% heterosexual, 11% queer, 11% heteroflexible, 9% bicurious; and 13% other orientations.

- Age, from 18-75.

We also conducted research through Censuswide, among a sample of 6,000 people split evenly across the U.K., U.S. and Netherlands who are not necessarily on Feeld (referred to as non-Feeld Members). The data was collected between 09.10.2024 - 24.10.2024. Censuswide abides by and employs members of the Market Research Society and follows the MRS code of conduct and ESOMAR principles. Censuswide is also a member of the British Polling Council.

- 34% identified as male, 49% female, 9% trans (inclusive of trans human, trans man, trans woman, transfeminine, transmasculine, trans non-binary, and two-spirit), 7% other genders.

- 43% identified as straight, 23% bisexual, 7% gay, 6% lesbian; and 19% other orientations.

- Age, 18-55+

Thriving Together

But what is a trustworthy online space? “Trust and safety” is a term developed by the industry to describe approaches for understanding and addressing potentially harmful content or conduct that may be associated with a given platform.

Just as there is no solitary definition of trust and safety, there is no singular approach or one “right way” to create safer dating spaces. For the purposes of this report, we refer to research and definitions across public health4, social science5, human rights6 and psychology7,8, which highlight how safety and trust have a reciprocal relationship. Individuals typically cannot experience safety if there is not established trust in the underlying social fabric of a group9. Hence our guiding definition is based on the ability for people to trust one another.

When asked which features of digital platforms help facilitate safer connections, those surveyed reported on a range of features that contribute to feeling safer while dating. Having control over personal information was most highly valued by 58% of Feeld Member respondents, followed by 53% who believe that blocking and reporting features are the most desired tool for creating safer environments. These results echo ongoing research on perceptions of safety in the field of Internet Studies. People view having control of their information as integral to safety and well-being and when online platforms affirm this need, individuals increase their trust in online spaces and in digital technologies10.

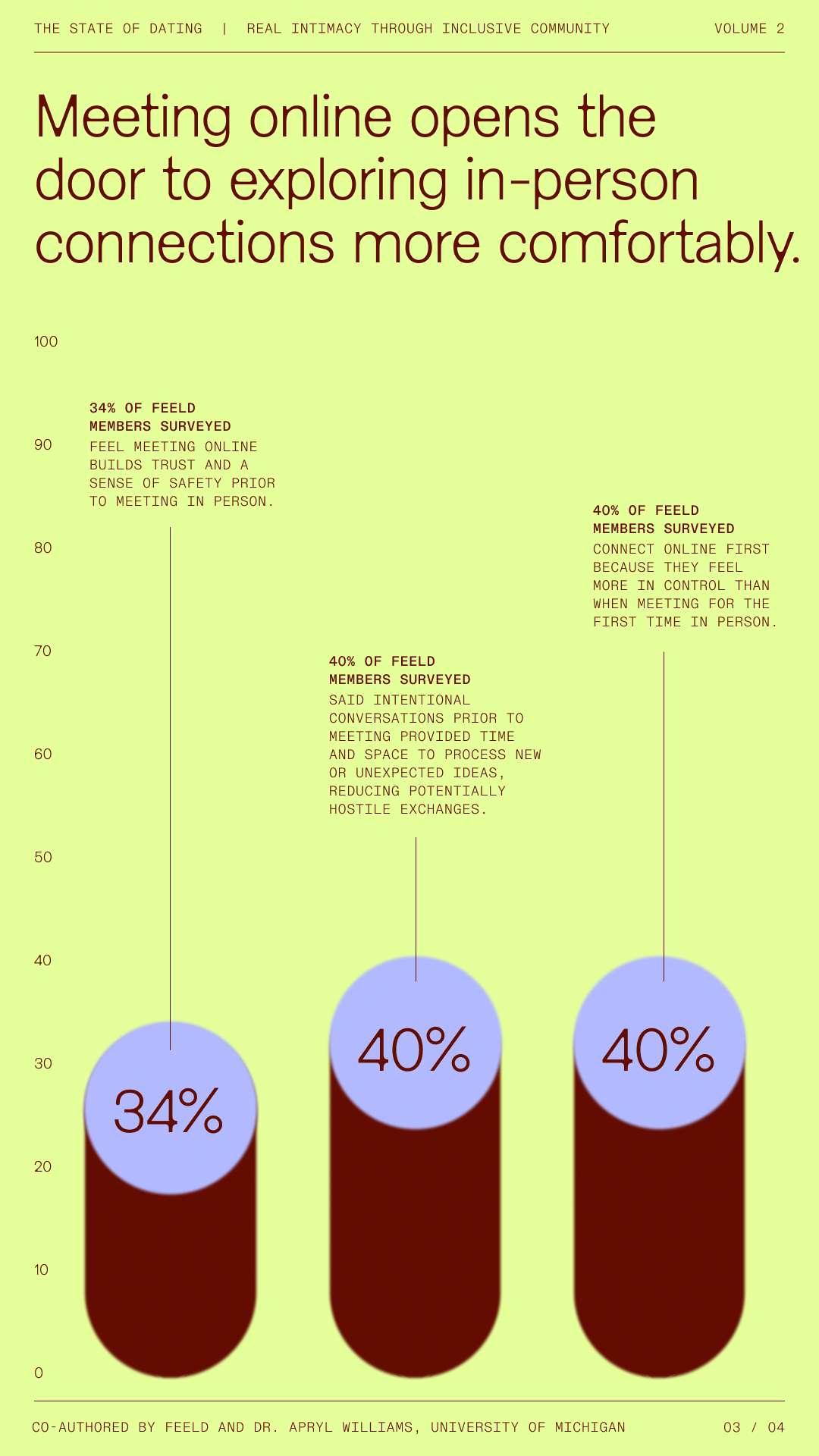

Sexual and emotional freedom flourish when safety is not a privileged commodity. Over the years, Feeld Members have shared how they feel empowered to connect with others more meaningfully on the app because the platform encourages authenticity. Members lean into this freedom by relying on creating deeper connections on the app before meeting in person. In fact, 40% of Feeld Members connect online first because they feel safer and more in control than when meeting for the first time in person.

People are looking to build relationships, seek intimacy and maintain friendships—even if the struggle is real. Overall, 49% of non-Feeld Members surveyed report turning to digital intimacy because they can be more selective about their connections and disengage when uncomfortable. This is a silver lining amongst the frustrations of online dating—it is not always possible to safely disengage in person. Because online dating offers such a distinct pathway of emotional and physical intimacy, digital platforms have the ability to serve as safer, more inclusive spaces for self-expression and exploration—when built and maintained with the right intention.

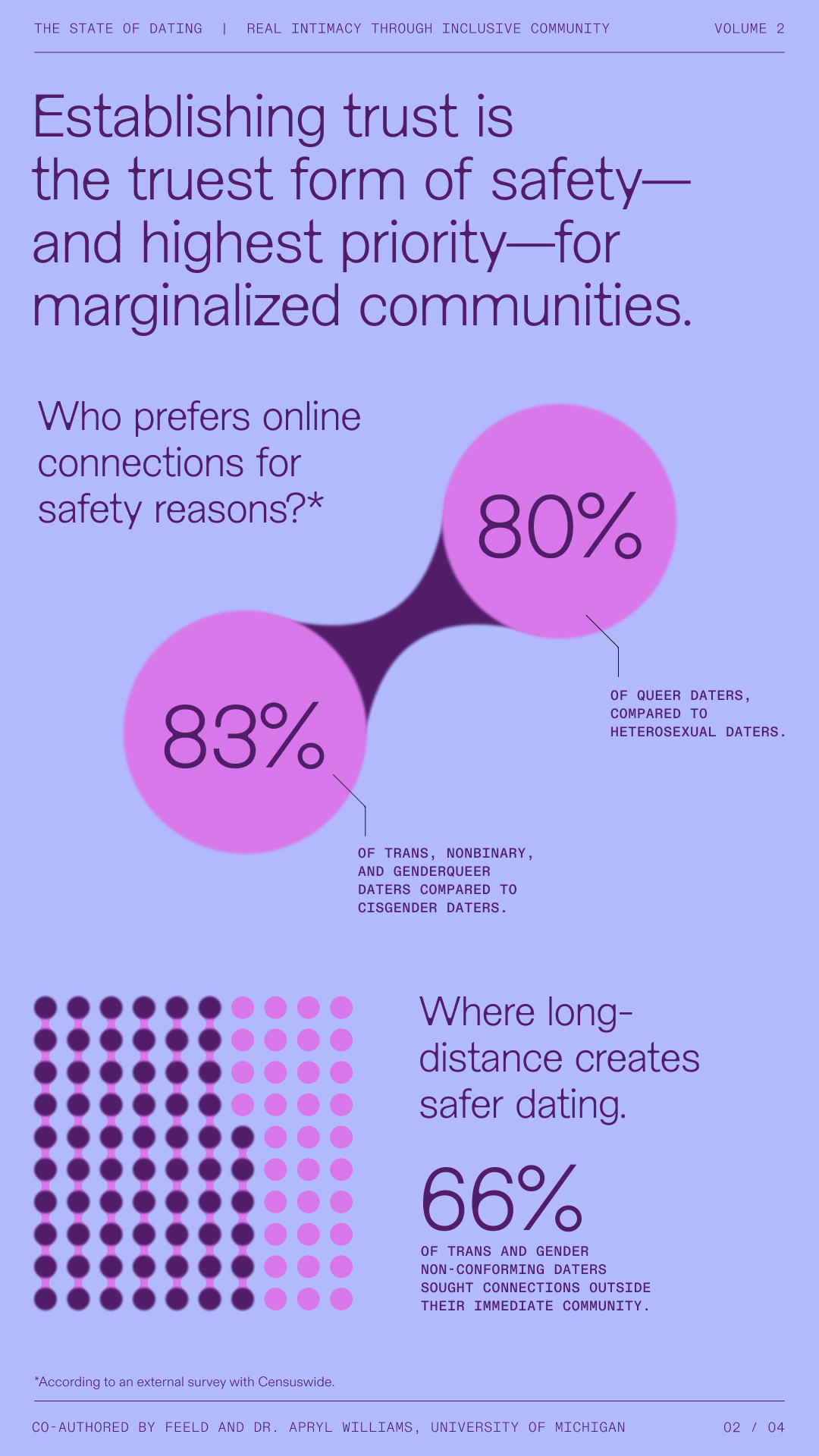

This is particularly true for marginalized communities. Based on non-Feeld Members surveyed, non-heterosexual daters are still 80% more likely than heterosexual daters to prefer online connections for the safety, comfort and expanded community they provide. Further, queer respondents reported being 66% more likely to seek connections outside their immediate community, and are also 120% more likely to report feeling more comfortable online compared to cisgender individuals. These results suggest that safer spaces in online dating can encourage more authenticity and openness for minoritized communities, which must be taken into account as a key consideration for both the inclusive design and safety practices of these types of platforms.

Likewise, 83% of genderqueer, trans, nonbinary and other non-cis individuals surveyed say that they are more likely to choose online dating than cisgender respondents, and over 30% of non-cis Feeld Members surveyed are more likely to report feeling more comfortable meeting online compared to cisgender Members.

Beyond the convenience, digital platforms provide an invaluable opportunity for the evaluation and assessment of potential connections—with more than half of Feeld Member respondents reporting that they prefer meeting online because it allows them to vet connections before investing time, energy and money. These survey responses suggest that the quality of our dating apps and the intentionality of the communities they build matters, especially for gender, sexual and racial minorities looking for intimacy while maintaining their well-being.

This means that we could be more expansive about how we consider personal preferences and be more thoughtful about designing for the safety of those with marginalized identities. Marginalized daters, whether neurodivergent, queer, undocumented, transgender, persons of color, etc. and especially those at any intersection of these experiences, encounter unique challenges to dating in-person11, 12. With careful and considered ethical design, digital spaces provide a unique opportunity to create safer environments for these groups.

Finding Intentionality in Online Dating

In creating a non-prescriptive platform that enables affirming and authentic connections, Feeld’s intentionally inclusive model creates structures that promote curiosity about ourselves and others13.

This kind of intentionality requires attention to detail and the creation of a value system for a community that must be approached as a shared responsibility. How do we get to a point where there’s a shared contribution for both companies and individuals in creating spaces where authenticity and intimacy are cherished community values?

Easier said than done, right? We have to figure out if the person we’re connecting with is even a real human, determine if the vibe is right, and then think about getting together to link in person. Then we hope that the person we’re meeting isn’t a secret racist, misogynist, homophobe, transphobe, or otherwise bigoted.

But the solution isn’t all that far off. The dating industry is well aware of experiences of toxicity on the apps and, in fact, they devote a great deal of time to tracking and reducing toxic behavior. The missing puzzle piece is that these safety measures are often designed primarily with mainstream users in mind.

But What About Us?

Dating apps are a unique collective space where culture, technology, privilege, and power collide, often increasing rather than ameliorating the effects of sexism, homophobia, racism, transphobia, xenophobia, and ableism14, simply by existing. For better and for worse, platforms can become a mirror for cultural phenomena. In the most intimate of spaces, individuals can often hold onto long-outdated beliefs about what kind of people should be together. Though permitted on some dating platforms as freedom of speech and an expression of personal preference, desires around body type, sexual appearances or race speak to a culture of body shaming, toxic masculinity, and racism that can pervade digital intimacy platforms15.

While many ascribe to these as personal preferences, it begs the question—why do these preferences exist at all? As a social scientist who researches race, gender, and technology, I argue that these ideologies about dating are shaped by our parents, friends and families, and our larger social culture, which directly influence how we perceive and connect with others.

Many people’s version of the ideally attractive human form is heavily influenced by stereotypical beauty norms in pop culture, which are expressed as a preference for lighter skin tone, smaller body size and slender composition, and light hair and eye color16. This means that individuals receive messaging from mainstream media about who they should desire, and may come to believe that desires for the societal standard simply exist as a natural and neutral social fact.

But this obsession with the highly celebrated ‘ideal’ form ignores a fundamental human truth: beauty (and desirability) is in the eye of the beholder. And some “beholders” are often using these platforms - both knowingly and subconsciously - to perpetuate the social stereotypes they are fed instead of opening themselves up to new experiences that dating platforms have the ability to provide.

Homogeneity of Thought

Online dating has become a centralized way for individuals to form romantic and sexual connections. However, as we’ve seen for many users, particularly minoritized groups, these digital spaces can be fraught with challenges that extend beyond mere superficial interactions.

In my own research, conducted in collaboration with graduate students in the Bodies Identities Intimacies and Technologies (BIIT) Lab at the University of Michigan, Black women reported feeling like a sexual commodity when using dating apps, reflecting that their bodies are deemed as less valuable in the sexual economy17, 18 Further, Black women expressed feeling as though dating apps, as they currently stand, might put them at a disadvantage, specifically because of their Blackness, which inherently hinders the formation of intimate connections by inducing feelings of racialized objectification and social inequity19. One study participant stated that online dating has a way of perpetuating “preferences, even if it’s rooted in racism”20. What’s critical about human intervention in operating dating apps is in seeing and presenting dating app users as whole people with nuanced and individualistic needs rather than data sets brought together by surface-level identity.

Frankly, it’s understandable for some people to feel that if they’re not a cisgender, straight-presenting, neurotypical White person, some dating apps were not designed for them21. Non-intentional safety practices, though often well-meaning, are not enough to cultivate the kind of community so many of us crave—authentic, safer, and beautifully diverse. And we’re not just talking about surface level visibility. We mean diversity of thought, of racial and ethnic identity, of gender identity, of sexual orientation, of religious belief, of kink, of queerness, and so much more.

Say What?

In my own sociological study, I have observed the outcomes of this homogeneity of thought firsthand. While conducting research for my book Not My Type, a culmination of seven years of studying dating apps and dating site users, I interviewed 100 daters of varied racial, ethnic, and gender identities about their experiences on mainstream dating apps. Black and Asian women daters in the U.S. who used conventional dating sites reported being unprepared when others initiated racialized role play without previous conversations about consent or interest.

This research can arguably extend to other minoritized groups and desire sets that use slang and playful turn of phrase, and may disadvantage daters who prefer clear and direct communication about desires. For example, out of surveyed Feeld Members, 86% of trans femmes, 89% of trans mascs, and 97% of those who identify as agender express a strong preference for bios that state interests and desires as a path towards the prospect of digital intimacy that may eventually translate into in-person connection.

There is also a void in the market for platforms that create space for app users to explore topics that are largely still seen as taboo22, which - when embraced - encourages more curiosity amongst their users23. For Feeld Members, kink and BDSM consistently ranks as the most common area of exploration (42%) across all gender identities, followed by an interest in threesomes/foursomes/moresomes (38%) and exploring ethical non-monogamy and open relationships (30%). Some mainstream platforms that filter out the consensual sharing of kink may signal that there is no respectful way to communicate non-traditional play; inadvertently suggesting that these community members are not seen and/or are not a priority.

Breaking the Dating Mold

While individuals are responsible for their actions, dating platforms influence their community by designing the spaces in which they interact, creating the opportunity to facilitate open communication about nontraditional desires. By encouraging upfront transparency in user bios in areas like desires, gender and sexuality, dating app platforms can help stimulate curiosity and foster more comfortable environments for users to share about themselves.

For example, 3.5x more Members feel that people are not as transparent on other dating apps about what they're looking for as they are on Feeld. With people continuing to seek connection through dating apps, and recognizing their unique benefits around providing safer, more comfortable opportunities to explore, it’s clear that an intentional community is born by the space in which it moves and lives.

As digital human rights activist, Afsaneh Rigot notes, digital spaces that are inclusive by design, prioritizing social equity and safer exchanges of information, will naturally breed a community of members who share similar values24. In turn, this can create the levels of intimacy - on and offline - that they’re seeking.

First Do No Harm

The interesting paradox is that while marginalized communities are no strangers to the risks associated with discriminatory and limiting ways of being online, they continue to find value in the opportunities for connection that online dating platforms provide. If we recognize that people outside the mainstream are treated differently, how can we work together to utilize harm reduction strategies more uniformly on these types of platforms designed for mainstream use?

Feeld data show that 34% of its Members surveyed feel that connecting on online platforms helps build trust and an increased sense of safety before meeting in person. Online connectedness may offer another pathway to harm reduction: approximately 40% of those surveyed conveyed that digital intimacy platforms facilitate intentional conversations by allowing daters more time to process and respond to new or unexpected ideas—possibly reducing the kind of hostile exchanges that occur when individuals do not feel they have space to lean in with genuine curiosity and kindness.

By adopting equity-driven strategies and incorporating diverse perspectives, more dating apps have the opportunity to better support their most vulnerable users as much as they do their most ‘valuable’ from a business perspective25. Because when we prioritize safety for those in the margins to explore, the entire community benefits.

Next, Make A Change

Though this inclusive approach to safety should be a baseline in dating communities, it is only one piece of the puzzle. Trust, transparency, and accountability are also vital to safer dating spaces. Online platforms - and their communities - can benefit from continuously trying to offer spaces that encourage openness and genuine connection for all groups, especially for trans and queer individuals who could feel freer to express their identities if these structures were in place.

We all know dating is hard. But it can be a lot easier to find the intimacy we crave if dating app users prioritize seeking out communities that champion authenticity. Despite the many challenges of digital spaces, there are also many benefits. With the right intentionality, dating companies have the opportunity to increase visibility and, ultimately, trust for marginalized people to form deeper and more curiosity-led connections, especially for minoritized groups.

References

1 Vongels, E.A. and McClain, C. (2023, February 2). Key findings about online dating in the U.S. Pew Research. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/02/02/key-findings-about-online-dating-in-the-u-s/

2 McClain, C. and Gelles-Watnick, R. (2023, February 2). From Looking for Love to Swiping the Field: Online Dating in the U.S. Pew Research. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2023/02/02/from-looking-for-love-to-swiping-the-field-online-dating-in-the-u-s/#fn-28993-1

3 More details under Survey Respondents.

4 Institut national de santé publique du Québec. (2018, August 17). Definition of the concept of safety. https://www.inspq.qc.ca/en/quebec-collaborating-centre-safety-promotion-and-injury-prevention/definition-concept-safety

5 Mitchell, J., Vella-Brodrick, D., & Klein, B. (2010). Positive psychology and the internet: A mental health opportunity. E-Journal of Applied Psychology, 6(2), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.7790/ejap.v6i2.230

6 Rigot, A. (2022, May 13) “Design From the Margins.” https://www.belfercenter.org/publication/design-margins

7 Wilson, L. C., & Liss, M. (2022). Safety and belonging as explanations for mental health disparities among sexual minority college students. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 9(1), 110–119. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000421

8 Hurd, B. et al. (2022). “Online racial discrimination and the role of white bystanders.” American Psychologist, Vol 77(1), 39-55 https://psycnet.apa.org/buy/2021-58178-001

9 Jozsa, K. et al. (2021) “‘Safe Behind My Screen’: Adolescent Sexual Minority Males’ Perceptions of Safety and Trustworthiness on Geosocial and Social Networking Apps”. Arch Sex Behav 50, 2965–2980 https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10508-021-01962-5

10 U.S. Department of State. (2024). “United States International Cyberspace & Digital Policy Strategy - United States Department of State.” United States International Cyberspace & Digital Policy Strategy, https://www.state.gov/united-states-international-cyberspace-and-digital-policy-strategy/

11 Oliver, D. (2021, August 30). LGBTQ and straight, cisgender dating are vastly different. Or are they?. USA Today. https://eu.usatoday.com/story/life/health-wellness/2021/08/30/dating-lgbtq-community-challenges-they-face-tips-for-future/8254479002/

12 Maldonado, S. (2024, June 7). Laws meant to keep different races apart still influence dating patterns, decades after being invalidated. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/laws-meant-to-keep-different-races-apart-still-influence-dating-patterns-decades-after-being-invalidated-229246

13 Feeld. (2024, February 22). Four seasons on Feeld with…Nicole. Feeld. https://feeld.co/ask-feeld/how-to/four-seasons-on-feeld-withnicole

14 Stacey, L., & Forbes, T. D. (2021). “Feeling Like a Fetish: Racialized Feelings, Fetishization, and the Contours of Sexual Racism on Gay Dating Apps.” The Journal of Sex Research, 59(3), 372–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2021.1979455

15 Smith, J. G., & Amaro, G. (2021). “No fats, No femmes, and No Blacks or Asians”: The role of body-type, sex position, and race on condom use online. AIDS and Behavior, 25(7), 2166–2176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-03146-z

16 Padinka, M. (2021, July 2). Are your dating preferences racist?. Mic. https://www.mic.com/life/are-your-dating-preferences-racist-82343271

17 Banks, J., Monier, M., Reynaga, M., & Williams, A. (2024). “From the auction block to the Tinder swipe: Black women’s experiences with fetishization on dating apps.” New Media & Society, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448241235904

18 Adrienne, D. (2022) "Don't Let Nobody Bother Yo' Principle": The Sexual Economy of American Slavery, in Sister Circle: Black Women and Work 15-38. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_scholarship/179/

19 Stacey, L., & Forbes, T. D. (2021). “Feeling Like a Fetish: Racialized Feelings, Fetishization, and the Contours of Sexual Racism on Gay Dating Apps.” The Journal of Sex Research, 59(3), 372–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2021.1979455

20 Williams, A. (2024). Not My Type: Automating Sexual Racism in Online Dating. Stanford University Press.

21 Colwell, A. (2022, May 9). Irish queer neurodivergent folks open up about dating. GCN Magazine. https://gcn.ie/irish-queer-neurodivergence-dating/

22 Feeld. (2023, February 2). Feeld × Screen Shot: On ethical non-monogamy. Feeld. https://feeld.co/ask-feeld/how-to/ethical-non-monogamy-what-it-is-and-how-to-explore-it

23 Marshall-Genzer, N. and Soderstrom, E. (2024, October 22). People are ghosting big-name dating apps, as smaller platforms make a splash. Marketplace. https://www.marketplace.org/2024/10/22/her-ceo-dating-apps/

24 Rigot, A. (2022, May 13). “Design From the Margins.” https://www.belfercenter.org/publication/design-margins

25 Lee, Kate Sangwon. Examining Safety and Inclusive Interventions on Dating Apps by Adopting Responsible Social Media Guidelines. August 2023. ResearchGate, National University of Singapore.