How to nurture a relationship—and a political movement.

An interview with Dean Spade, author of "Love in a Fcked-Up World: How to Build Relationships, Hook Up, and Raise Hell Together."

On the afternoon I speak with lawyer, organizer, and writer Dean Spade, apocalyptic fires are tearing through my home state of California, swallowing acres of land. My Instagram feed glows with offers of help: couches to sleep on, meals to eat, clothes to wear. I am reminded of a truth that has crystallized for me since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic: Our safety is measured by the strength of our relationships. No one is coming to save us except for each other. And yet, when relationships sour or end, the fissure can become a barrier to the sustained political action our world so desperately needs.

In his new book, Love in a F*cked-Up World: How to Build Relationships, Hook Up, and Raise Hell Together, Spade argues that to build transformative movements, we must examine the gap between our political commitments and our romantic lives. This gap can feel excruciating. We might fiercely believe in bodily autonomy, yet find ourselves falling into manipulative behaviors when a lover has a new partner. A heart-wrenching breakup might compel us to tear down an ex in ways that undermine our shared communities. But, Spade insists, that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t fuck or fall in love with the people we organize beside. Instead, we must cultivate the skills to navigate these relationships with care.

“Of course we’re going to hook up with the hot, brilliant people in our movements—those who understand our passions and want to fight for liberation,” he writes. “As a feminist and a queer, I know how important sexuality can be as a site of transformation, expression, and community-building. Sexual and romantic relationships can be thrilling, meaningful spaces of self-discovery, support, and healing. But the excitement of these connections doesn’t guarantee they will unfold smoothly. Day to day, I’ve seen how difficult and destructive relationship conflict between organizers can be.”

Spade began organizing during the 1990s in New York City, where he was the founder of the Sylvia Rivera Law Project, a legal aid organization that provides support to trans people. He is also the author of Mutual Aid: Building Solidarity During this Crisis (and the Next), and an Associate Professor of Law at Seattle University. His latest book, styled as self-help meets the lessons of organizing, may seem like an unexpected next step in his career, but Spade explains that he has always been fascinated by how change happens, personally and in community. He knows what’s at stake as we move into a future shaped by climate chaos and the re-emergence of fascist leaders—and he wants us to have the tools to get it right.

I read that you’ve been working on this book for nine years. What were you observing in your own relationships and communities that made you want to dive into this project?

I started writing the book in 2015, but I have been working on these issues with friends and lovers since I was 18. I'm 47 now. It's always been clear that in order to address my own suffering and to show up in the movement spaces that I want to be in and act according to my values, I needed to do a lot of work on myself. I needed to be like, wait, Why is that thought in my head? Why do I feel competitive, jealous, or like I want to disappear? Why am I having such a strong shame reaction in this relationship, friendship, or meeting? That kind of work has been essential for me to do anything I wanted to do.

A lot of this book comes from my own experiences of being in groups that fall apart because people go into emotional reactivity. That of course makes sense, but there’s often not self-awareness about the fact that I feel left out or I can't stand that people are disagreeing with me or I feel like I have to be the boss of things—and now I'm destroying the group. People's unconscious and sometimes unethical behavior can impact life or death projects that our communities need.

I’ll also say that the area of sex, love, and romance can be really fun, wonderful, and enlivening. At the same time, it is one of the most dangerous parts of our lives. The most likely person to hurt me or kill me is a lover or someone who wants to be my lover. It's political. It's gendered. It's racialized. It's about capitalism. It needs so much of our attention yet it gets dismissed as “women’s work.” With this book, I’m trying to bring some of the useful tools people have developed in the self-help realm, and put them in the frame of our feminist, anti-racist, anti-capitalist, anti-colonial values. It feels like a missing piece.

You start with the book with this really helpful term. What is the “romance myth" and how does it shape how we treat each other?

I use the term “the romance myth” to talk about a cultural norm and narrative that tells us that romantic relationships are the most important relationships in our lives and that they will inevitably make us happy. The myth encourages us to isolate into our relationships and seek our deepest emotional needs from those partnerships, to ditch friends and projects for lovers. That pattern can be really harmful for collaborations and relying on each other in community. It also produces isolated relationships where people don't tell others about things that are happening in their [romantic] relationships.

A lot of people think their life is a failure if they don't have this kind of relationship or will try to push each other up a romance and relationship escalator. People hold each other to standards—marriage, kids, monogamy—that didn't actually come from consensual negotiation or exploration of their desires, but instead are from this cookie cutter, cultural script.

All of these things really undermine our ability to have satisfying connections and robust support systems. We all need a lot of people in our lives to get different kinds of support. The romance myth is this packaged fantasy and we need a political analysis in order to become more choice driven with our lives.

Can we play with and find pleasure in the romance myth without allowing it to feed into these more harmful dynamics?

I think one thing this question links to is the idea in our culture that there are “good” feelings and “bad” feelings. Like it's “bad” to feel angry, sad or jealous and it's “good” to feel happy all the time. We’re allowed a very limited emotional range—and that can also happen politically. We can tell each other you’re bad if you have jealousy because we should all want autonomy or you’re bad if you want to possess your lover. Can we look at strong feelings that sometimes motivate unethical behavior and instead of thinking the feelings are bad, see if we can play with them?

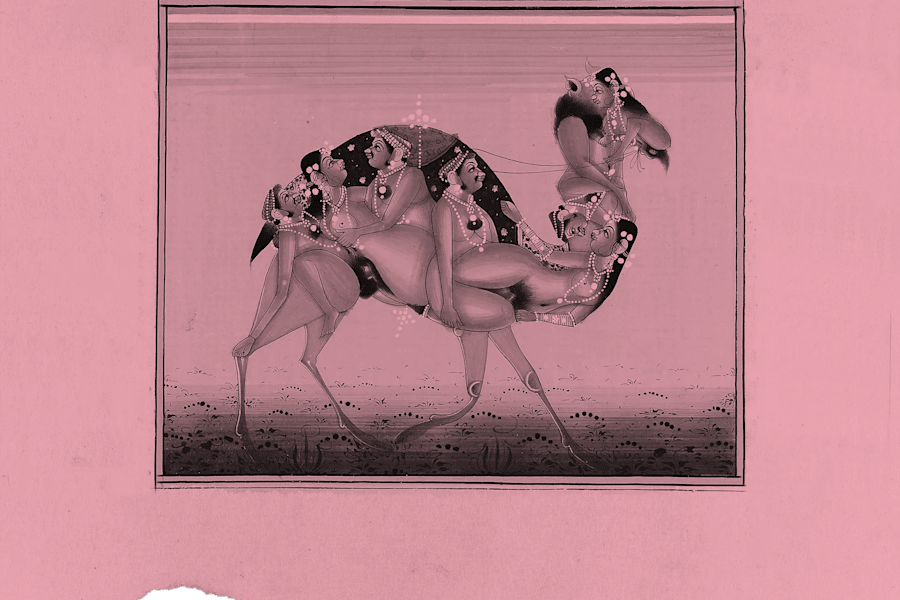

If I have a desire to control another, could I negotiate with someone to have a scene where I get to control something about them that ends? I’m referring to using BDSM and kink frameworks that are [based on] radical feminist ideas about power and consent. If we do these behaviors unconsciously and rush into romantic relationships, we can end up with a situation where one person does all of the housework, and it's not fun. Or someone who doesn’t have the friends they want because their lover is jealous. Those are very troubling dynamics. But if instead people could identify these feelings and be like, Let's have special things we do about that and stick to a broader principle of autonomy, compassion, and having a big support system at the same time.

I think there are a lot of surface references to kink in today's popular culture and queer culture, but I don't think a lot of people have gotten a chance to do some of the reading about the actual radical potential of kink as a place to enjoy and support the parts of ourselves that may be scripted by a culture of control and hierarchy. It makes sense that some people sometimes want to be completely subsumed by another, or some people want to have total domination over another sometimes. Kink can be a resource for having those experiences without giving up the other parts of our lives.

Why do you think there’s often such a strong gap between our political ideals and our personal, sexual relationship?

I have noticed that people act their worst in this realm. There's something about our relationships that very frequently enters us into what I think about as the romance cycle. The idea that I'm projecting on you so positively at the beginning. All of these emotions come up. I'm going to finally feel the love I always wanted to feel. You're going to truly see me and hear me. I'm going to have true belonging and safety—whatever I didn't get as a child.

And then, inevitably, people disappoint us because they’re human—and now my disappointment is proportional to my positive projections. Culturally, as soon as you disappoint me, I can use a whole slew of mean narratives to say about a lover like, “Oh, he's a zero.” What may be missing in the analysis is that I was caught up in a very common cycle of projection—and that's okay. The more I'm aware of it, the more I might be able to not fully act out on you when I feel that way, and not be as damaging to myself or others in our community in my strong emotional state.

Yes—and becoming aware that that’s what we’re actually doing. It’s amazing how often I forge the same relationships again and again without realizing it. What are the stakes of learning how to do this better for our movements?

I think a lot of people are aware, since the second Trump election, the fires in L.A. that are happening, the recent hurricane in North Carolina, and the ongoing genocide in Gaza that the stakes are extremely high. No one is coming to rescue us. Appealing to elites for change is ineffective. We really just have each other. If we don't know how to have each other's backs, and fall apart because of emotional reactivity in our groups, we won’t be able to save each other's lives. I just had a meeting with some people who do a really amazing mutual aid project that is life or death for the people who are receiving medicine through it, and they had a really bad conflict and didn't do the work for a week, and people died. That is the nature of it.

Right now, we need to be thinking about taking very big risks together, like helping people get abortions that are illegal. Helping people get trans medicine that is illegal. Helping people hide from ICE and the police. Things were already horrible and are turning up very badly, and so the strength of our ability to trust each other, to stick together when we're stressed out and impatient, to be with people whose personalities irritate us, to collaborate with someone even though we had a really bad breakup is essential. It has always been, but it’s so accelerated and will be for the rest of our lives because we're going to be living with the impact of the ecological crisis that is only speeding up. There's not really any alternative except for us to come together. I think we all feel how unprepared we are. We need everyone mobilized in mutual aid projects. We need everyone learning about how to have greater solidarity. We need everyone breaking down ideas that keep us apart [and] that pit us against each other. We’re not there.

At the same time, we have to hold wow, the world is literally on fire and there’s so much agony with the fact that it's so fun to flirt with people. It's so wonderful to have friends you want to make art with. It's so amazing to feel real solidarity and to soften our hearts and care about people we've been told not to care about. We have to hold the lightness, the beauty, and the aliveness while we do the hardest things possible. We really have to choose that.

How do we give ourselves grace in the gaps between what we know we want and the feelings of jealousy, fear, or shame that can come up? How do we not bypass those feelings but not let them control us either?

I think polyamory is a really good example of that. For me, jealousy is really hard. I feel really judgmental toward myself for it because it feels like it's something I inherited from a broader culture. My truest belief is that I want everyone in my life to have all the connections they want to have and for their life to be full of love and aliveness and to develop their sexuality in any way they want. And yet I sometimes feel very jealous about my lovers. And so to me, the work is to ask, can I be kind to that part of myself? Can I ask for some kind of reassurance from people if that's appropriate? And also know that they can say yes or no to being available for that support. Nobody is required to give me any particular kind of support. That's why I have a robust support system, hopefully. So even if the person I most want to hear that reassurance from can't or won't give it, I can get that elsewhere. And then how do I generate my own safety by having boundaries? We can feel a sense of safety generated by taking care of ourselves. We're allowed to try to live our values. It's not about perfection. It’s okay if it’s hard.

A lot of people I know are like, I could never have an open relationship because jealousy feels bad. And I'm like, you know what? Feeling bad is actually okay. It's okay to be scared and do something anyway. “Bad feelings” are a part of being alive. Part of our job is to be able to feel more of our emotional range and when you open up the “hard stuff”—the grief and anger—then you can feel more pleasure and joy. Right now we're living in apocalyptic times, so the appropriate feeling-scape includes total devastation, rage that greed has produced ecocide. And also wow it's so beautiful to be in a body on earth. The air feels good right now. I love eating this. It’s amazing to have sex. It's incredible to find someone to talk to who feels the way I feel. When we cut off one side of the emotional range, we lose a lot of access to pleasure and appreciation—and that's kind of all we have right now.