179 East 71st Street, New York

Evenings with Saul Steinberg and Hedda Sterne

Download Feeld

Fran Hoepfner on learning that having a crush on vacation is life-ruining and delightful, that having big hair is an inevitability, and that Beethoven is somehow always involved.

This is Text Me When You’re Done: a column all about sharing what you want with who you want. We’re inviting contributors to tell us about the things they always turn to as a way of explaining who they are—the works of art, articles of interests, or other tangible elements that they refer to as a way to understand them. In this instalment, Fran Hoepfner revisits a classic of romantic comedy.

I watched James Ivory’s 1985 adaptation of A Room with a View for the first time in the summer of 2018, lonely, single, and bored, with my laptop overheating on my stomach, in a city where I knew no one. I watched it over the course of a July afternoon, then again the next day. Then once more that week. By the end of the summer, I’d watched it three more times, once dragging my friend to see it at a nearby rep theater where Ivory himself sat in attendance. The audience laughed and gasped in all the right places: the simple beauty of his directing and the warm cadence of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s script working hand in hand to delight and awe.

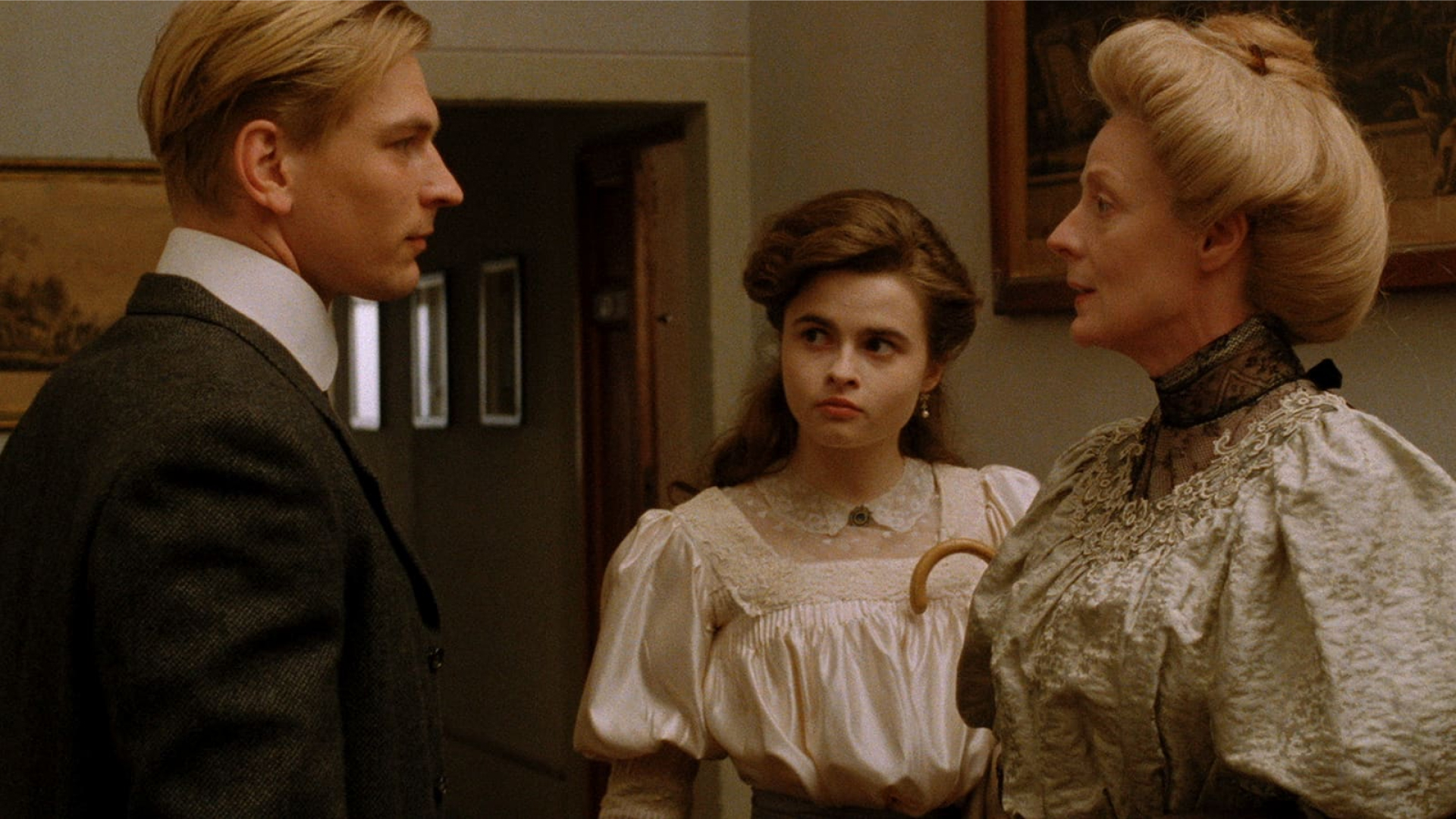

A Room with a View has everything streaming television is chock-full of with triple the quality: the Italian vistas of The White Lotus, the searing class commentary of Succession, and the sensual ribaldry of Bridgerton. When people talk about the romcoms of the ‘80s and ‘90s, they talk about the effortlessly cool writing of Nora Ephron or James Brooks, but I’ve always thought they were missing A Room with a View. Just like When Harry Met Sally… and Broadcast News, this is a movie anchored by a moody heroine with big hair who stumbles upon love where she least expects it. Our romantic lead is one Lucy Honeychurch, played by a brooding 19-year-old Helena Bonham Carter, in poofy lace and a poofier perm, who ventures off to Italy where she meets a blonde socialist (who can relate) who threatens her boring, annoying relationship with her soon-to-be-betrothed Cecil Vyse.

But the greatness of A Room with a View exists far beyond its context in other films and television shows. Its central love triangle has everything: pulpy romance novels, a kiss with tongue in the Italian countryside, an annoying little brother, a friendly priest, a surprising amount of full-frontal nudity, and, of course, Beethoven. Lucy’s decision to go against the grain and pursue a free-thinking and free-living lover in the context of rigid Victorian culture is framed as brave, utterly romantic, and above all else, a great annoyance to those close to her.

Casual movie-goers will know Helena Bonham Carter from her roles in Tim Burton films, or her witchy spin as Bellatrix Lestrange in the Harry Potter films. To see her gothic, off-kilter presence in a period-set romantic comedy is jarring, to say the least, but what is more late Victorian than someone who looks out of place in a big poofy dress? That Lucy Honeychurch is so moody and forlorn comes naturally to the great Bonham Carter, huffing about, her hair flying all over the place. Daniel Day-Lewis, who plays Cecil Vyse, is perhaps better known to audiences these days for his often-serious, “method” performances, though his outright comedic turn in A Room with a View feels like a predecessor to his arch turn as Reynolds Woodcock in Phantom Thread. Both are period-set romantic comedies, in their own way, and both men are fussy, particular, and laugh-out-loud funny. It is not just that Lucy isn’t attracted to Cecil; it’s that he’s unbearable (in the gentle hands of Ivory and Jhabvala, however, he’s also sympathetic).

Rounding out the love triangle is George Emerson, played with handsome grace by Julian Sands. Of course Cecil doesn’t have a chance! George is blonde and free-thinking—an oddity, no doubt, but a quiet, kind one. He does something no other man has ever done for Lucy: take her at her word. His socialist-adjacent tendencies and lack of self-embarrassment set him apart from every other person in town. This makes him something of a pariah, but what’s more romantic than a true weirdo? Sands plays George with a casual ease, an undeniable handsomeness. Though less of a household name to younger American viewers, his catalog in film and television ranges from the light to the serious, with one of his last roles being a stodgy military official in Terence Davies’s lush Benediction. Earlier this year Sands went missing on a hike outside of Los Angeles, his whereabouts still unknown. Returning to A Room with a View again and again grounds him, if not in reality, then on screen, big and beautiful and forever.

In the early days of the pandemic, when being a person with book and movie recommendations was as valuable as being a first responder (I’M KIDDING), I told friend after friend after family member to watch A Room with a View. “It’ll make you feel loved.” “It’ll make you feel like you’re on vacation,” I told them. “And let me know the second you finish how you feel about Mr. Beebe,'' the aforementioned friendly priest played by English stage legend Simon Callow. I waited while they watched, flipping through the film on whatever streaming service housed it at the time of viewing, or even scrolling through the special features on my Criterion blu-ray. I tapped my fingers. I practiced piano (real Lucy Honeychurch heads know). I got peevish. And then, inevitably, I’d get a “wow!” or a “love!” or a “I have Mr. Beebe fever,” or, best yet, “wow, three dongs in that movie!”

Being the age I am, I knew Ivory mostly from his screenplay adaptation of Call Me By Your Name, and in the most vague sense, from his collaboration with producer Ismail Merchant. But for the longest time, I had only narrow-minded thoughts of what a “Merchant-Ivory film” was. I did not consider them literary adaptations, nor did I note their queerness, that they were often written by a woman, that they were far odder and funnier and more romantic that I could ever conceive. Mostly I thought of them as stuffy, arch, and dated. Mike D’Angelo, writing for The A.V. Club, correctly pointed out that sometime in the 1990s, “‘Merchant Ivory’ itself became the cinematic equivalent of ‘Masterpiece Theatre’... It signified quality, but often in a pejorative way, suggesting something British and tasteful and stuffy and frightfully dull.” Exactly: those movies were for old people, and I was young, damn it!

I first started dating my now-boyfriend right before my 30th birthday. It is always great to start dating someone in close proximity to your birthday, so you have the excuse to make them do whatever you want to do. After a long day of shopping and wandering around lower Manhattan—only our fourth or fifth time hanging out together—he came with me back to my apartment for pizza and unwinding with my then-roommate and his girlfriend. I planned the ultimate early courtship test: watching A Room with a View. My boyfriend has eclectic, smart taste, but had never seen a Merchant-Ivory film (though he loved many a Pride & Prejudice adaptation). In my memory, he watched silently, thoughtfully, not giving away a verdict until it was over. “Are you kidding?” he asked when I ran this scenario by him. “I was laughing the whole time because of how goofy it is.” He recalled asking me to rewind a scene a number of times just to see the exact posture Daniel Day-Lewis holds while carrying a book. Regardless, he passed the test.

Since I first watched A Room with a View, I’ve moved to a new state and absorbed a number of other Merchant-Ivory films. Not all of them hit the same pleasure sensors as the Forster adaptations but I don’t regret my time with them. More than their arch sensibilities or wonderful production design, they present a world worth falling in love within, a crucial aspect to any romance. The landscape of period romance does not begin or end with Jane Austein and her myriad rip-offs, but it deepened with the frantic, political, and laugh-out-loud funny nature of these costumed comedies. Moreover, to appreciate A Room with a View was to appreciate my own sensibilities: that having a crush on vacation is life-ruining and delightful, that having big hair is an inevitability, that Beethoven is somehow always involved. I still need to know what all my friends think of it, and when the nights are long and boring, the Criterion Blu-ray sits on the shelf. “There’s always A Room with a View,” my boyfriend will suggest, which is true.

Evenings with Saul Steinberg and Hedda Sterne

Aren't we all just part of a great literary, liberatory tradition?