“The climate crisis is a romantic crisis:” an environmental roundtable

How does the climate crisis shape our most intimate relationships, and what does the environmental movement mean for our collective liberation? Six climate activists talk to Feeld.

The climate crisis is real, it’s here, and it will continue to affect our lives in immeasurable ways. Feeld reached out to activists—including a legal scholar and civil rights attorney, an award-winning poet, a queer environmental educator, and several journalists working across different mediums—who take an intersectional approach in covering the catastrophic impacts of climate change on both systemic and personal levels. We asked them about the ways in which the climate crisis shapes our closest relationships, how fights for environmental justice are tied up with movements for queer liberation and racial equality, and what we can learn from one another.

How do you see climate change shaping our romantic, familial, or social relationships in the present moment? How do you think that could change in the future?

“I actually talk about this topic frequently. A few of my friends—who are family, who are platonic or romantic lovers—and I discuss buying some land outside of the city to cultivate together. I wonder about the ethics of having children in such a world, but we talk about raising kids together, a multi-personed family. I think that this crisis calls for a grand reimagining of what is ingrained in us. Our minds are often trained to consider energy storage, infrastructure, power grids, clean energy, agriculture, etc., but I think we ought to be considering who we are with other people. How might we grow, love, play, and learn together? I think there’s real beauty in those possibilities.” —Liana DeMasi

“The climate crisis is an educational crisis. It’s a romantic crisis. And it’s a loss of culture crisis. The more we see climate disasters affect our communities, the more trauma and unhealed pain we have to open ourselves up to our loved ones. Relationships are tough when you are already dealing with a myriad of issues. It’s important that we build both romantic and platonic love. Even if you don’t see yourself with someone romantically, build platonic love, or vice-versa! We are never alone’ we have the fauna, flora, and fungi around us that are sacred living systems That have culture and history. I think the best way to sustainably love yourself in life is to continue building networks of friendships, lovers, and to have an open heart.” —Isaias Hernandez

“For people living in countries that are most impacted, it has led to a refugee crisis that is splitting families apart and forcing them to relocate to entirely new places. Other people are worried about starting a family during a time of crisis and are reconsidering the idea of having children—both because of the way the crisis will affect the next generation, and also because of the impact children will have on the planet. Other people are radically rethinking who they’re in relationship with and are trying to develop deeper and more attentive relationships with other species and expand our notion of kinship. As far as romantic relationships go, I think a lot of people are feeling like they need to either find their person to weather the storms with (literally in some cases), or hook up and experience the most pleasure possible in the present before things get really bad. I also think people are starting to think a lot more about what community aid looks like and moving away from individualism as they realize that we all need networks of support to survive both slow and immediate disasters.” —Ash Sanders

“Climate change will [place] stress on all of our infrastructure, whether that’s our roads and drainage systems or the less tangible infrastructure of the family. In order to survive, I think we’ll need to be more flexible with how we think about kinship networks and networks of support.” —Irene Vázquez

“Personally, my own family dynamic is already being highly impacted by the effects of climate change. In South Florida, my sister said she was triggered the other day by a light fall of rain—pleasant in many circumstances, but not after a night of historic rainfall and flash flooding. Here in Northern California, I’ve become a mom who’s easily triggered by a gentle fall breeze, which also used to be lovely before it became the thing that destroyed Paradise. How we react to these climate ‘triggers’ can affect anyone we share our lives with, whether it’s your partner or kid seeing you lose it over a change in the forecast, or the neighbor you need to let stay with you (and their yippy dogs too) because their house is more flooded than yours. It creates more moments for us to show our vulnerability—as well as how we rise to a challenge, help each other out, and find creative new ways forward, together. All that plays a huge role in our relationships!

It also seems like one's stance on climate change is getting more relevant for dating. For example this young couple I recently wrote about fell in love in part over their sense of shared resilience. They each wanted to be with someone who they could picture navigating life’s bigger challenges, like climate change, while still being able to find the joy, and even silliness, in day-to-day life.” —Daisy Simmons

“As an older millennial, I’m part of the iPhone-using, participation trophy-collecting, avocado toast-eating generation that has been blamed for ruining everything from chain restaurants to home ownership to marriage because of our lazy, selfish ways. We’re apparently ‘selfish’ for deciding to delay or entirely forgo marriage and reproduction at the same rates as previous generations. But in all seriousness, we’re often coming to these decisions with anything but selfish intentions. Marriage, family, and child-rearing are all overshadowed by the specter of the climate crisis. Many, including myself, are grappling with the ethical implications of bringing a child into this world while knowing the climate devastation they will face, and the growing socioeconomic tensions that go hand in hand with a destabilized environment: experts have predicted more clashes over natural resources like water as they become scarce, a growing number of displaced people and [an increase in] forced migration (such as from sea level rise), increased food costs, and of course more extreme weather events. With such a future on the horizon, it’s hard to think about bringing kids to the mix. Of course, all of this has a negative impact on our mental health and increased rates of depression certainly makes it harder to think about marriage and committed romantic relationships. It puts additional strains on existing relationships as well. I think as the effects of the climate crisis worsen and are felt more broadly, we will see even fewer people choosing to have children, get married, or even form romantic relationships.” —Zsea Bowmani

How does the environmental movement overlap or intersect with other movements for liberation?

“It’s easy to say that climate change is the first existential threat of its kind, but that’s an inherently privileged perspective. Many people and species have faced existential threats before —from the extinction crisis facing non-human animals to the genocide of Indigenous peoples around the world, to the capture and enslavement of African people, to police killings faced by Black and Brown communities, and the threat of school shootings young people have to deal with every day. To fight (and win) against climate change, we need to address the root causes of these problems and overhaul the systems that depend on this logic. One of the root causes of the environmental crisis is colonization—a logic that views indigenous people and the natural world as expendable. Another is capitalism, which turns every relationship we have into a profit motive and sees the world as a place of extraction [and] profit. This is tied to environmental racism and classism, which puts the burdens of our current inequitable systems onto marginalized groups, exposing them to toxins, pollution, and health problems. We don’t just need to stop the climate crisis, we need to build a world in which a climate crisis can’t happen.” —Ash

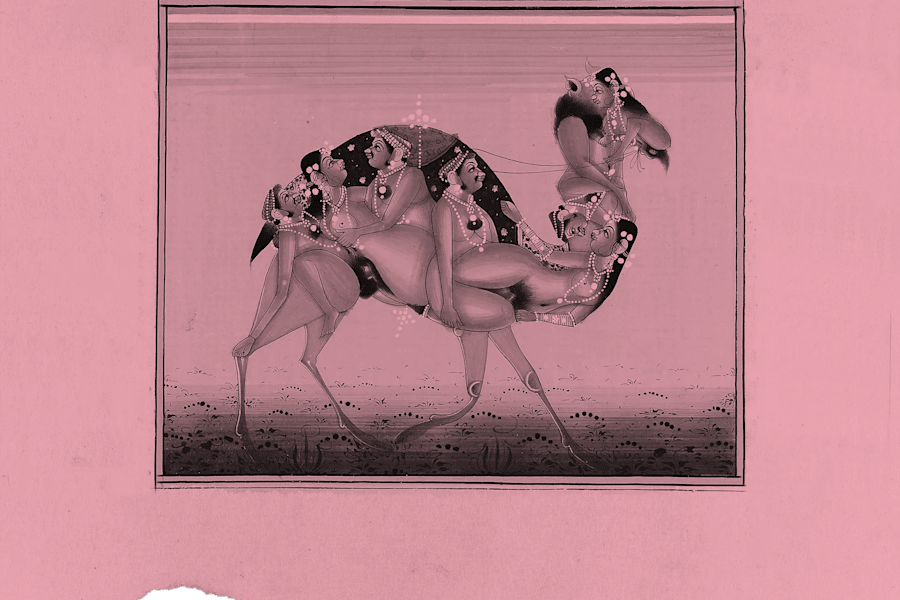

“Queer ecology! I believe that the intersections between queerness, land, and histories are rich in our movements. I feel that sometimes the LGBT community does not see the intersections between themselves and the environment. We are earthly beings. Some species have different sex-species or contain various sexes in one body, and I believe that should be celebrated in the way we navigate [the world] as humans. In order to bring conversations around queer ecology forward we must admit that there is no such thing as unnatural[ness]. Nature that we embody has always been based on diversity not uniformity. There is no perfection in nature, there is messiness, contradictions, and beauty in that weirdness of who we are. Being queer, weird, and diverse is actually a part of the larger culture of environmentalism.” —Isaias

“Movements for racial justice, economic justice, reparations, reproductive justice, land back movements—they all help determine who gets access to resources, including the environment. I do a lot of work with K-12 classrooms, and I tell them that the scariest thing about climate change is also the most empowering thing—that it overlaps with every aspect of our lives, but that means that whatever our unique skill sets are, there’s something that we can contribute to helping fight climate change.” —Irene

“It’s heartening to see the growing focus on climate justice—for a long time it felt like the perception was that environmentalists cared more about the planet than people. But lately there’s been a lot more emphasis on the human impacts of climate change, like how we’re all feeling them, every day, everywhere—yet its impacts are not felt or distributed equally. From extreme weather to rising sea levels, the effects of climate change often have disproportionate effects on historically marginalized or underserved communities. Today more people are calling attention to these inequities, and actively working to address them as part and parcel of decarbonization.” —Daisy

“As an environmental justice scholar and advocate, I’m glad to see the environmental movement is starting to catch up with EJ and other movements for liberation. Environmental justice began as a movement in the 1980s in Black communities precisely because environmentalism was largely concerned with things like water, trees, polar bears—the environment without the people (a problematic mindset that has contributed to the current climate crisis)—and failed to address environmental injustices that impacted their everyday lives, such as the intentional siting of toxic waste dumps and other polluting industries in poor, Black communities and other communities of color.

The 17 Principles of Environmental Justice drafted at the National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit provides a solid framework for understanding the ways in which the environmental justice movement intersects with other movements for liberation. Among other things, it affirms the fundamental right to political, economic, cultural, and environmental self-determination of all peoples; emphasizes the importance of labor rights, human rights, and bodily autonomy, including reproductive justice; and opposes military occupation, repression and exploitation of lands, peoples and cultures, and other life forms.” —Zsea

What do you think is being left out, ignored, or otherwise under discussed in the climate change conversation?

“This question is tough because there are a myriad of groups and peoples left out of discussions —or, if they are discussed, their perspectives are trivialized or minimized. We need to be considering, more fully and profoundly, how this crisis is and will continue to impact marginalized communities, especially BIPOC individuals and those near or under the poverty line. That means including these groups in conversation about what is needed in their communities and how those needs can be achieved. We also need to be repositioning how we discuss coal, fossil fuels, natural gas, etc. We need to be transitioning our energy sector to clean energy, but a lot of media and political coverage villainizes the blue-collar workers in those sectors. We need to be guaranteeing them green sector jobs and making them part of the transition. Essentially, we need to truly be ‘by and for the people,’ rather than the government and industry giants claiming that they know what’s best for the world they’re destroying. That involves a lot of change, but I don’t see a way out that doesn’t turn our current systems on their heads.” —Liana

“I think the environmental movement can too easily split between fighting for human life and fighting for animal life—between saving civilization, for example, or saving the polar bears. I believe that to solve the environmental crisis, we have to do both, and let one inform the other. Specifically, I think that to stop the climate crisis, we have to end ‘speciesism’—the belief that humans are inherently better than other species, and that their needs are less important than ours. Our future is bound up in the future of other animals, and I think we need to move from a more industrial environmentalism that only focuses on fighting for technological solutions—from solar panels to wind turbines—to one that also focuses on our relationship with the living world. To end speciesism, we need to see the climate and other environmental crises from animals’ perspectives. This includes thinking about extinction and how it affects wild animals, [and] thinking about our food systems and the exploitation and suffering of the animals we eat for food. We can’t build a just world for just one species.” —Ash

“I think we need a collective reminder that we can do hard things. For years climate communicators have been arguing between framing issues around hope and optimism, or doom and gloom. One approach, the debate goes, may inspire personal action, but it’s Pollyannaish and personal actions are pointless anyway. The other approach delivers the real story we need to hear—but it makes us feel like there’s no use trying, which is also not good.

I think we need both. People throughout history have endured crises while still finding joy—and living their lives, going to work, falling in love, planting gardens, having kids, making art—yet also while being able to sit with and face the overwhelming grief. As humans we’re primed for all the feelings—hope as well as fear and doubt—and I think we’re stronger when we give space for it all.” —Daisy

“Of course, there isn’t a single conversation on climate change whether you are talking about the United States or globally. That said, there needs to be more serious discussion about climate equity—that is, how will we address the fact that human beings have not equally contributed to climate destabilization, nor do we equally share the burdens. Island nations, for example, will become engulfed by climate-induced rising sea levels though they’ve produced little greenhouse gases, whereas large nations like the US or those of the European Union have contributed a disproportionate amount of GHGs (greenhouse gases). Even within groups, there are those who are pushed to the margins of society that, because of that marginalization, will be the most vulnerable to the impacts of a destabilized climate: people with disabilities, women and girls, LGBTQ people, poor people, and so on.

On that note, many people, especially Indigenous communities in the US, they’re already living the climate dystopia that scientists predict is in our future. Scholars like Dina Gilio-Whitaker and Kyle Powys White have written about climate and environmental justice from an indigenous perspective and how the legacies of settler colonialism, enslavement, genocide, displacement, and resource extraction has left much of Indian Country impoverished and environmentally devastated, so in a way, they already know how to survive what the rest of us will be facing. At the same time, however, our Indigenous siblings have a rich and nuanced understanding of our environment that has helped them live in a sustainable manner for millennia, and the importance of this traditional ecological knowledge is finally starting to be recognized by non-Natives and enter conversations about the environment and climate change more broadly.

Finally, I think people deeply underestimate the revolutionary change that is necessary to get us back on the right course. Many of the conversations at institutional levels are about ‘sustainability’—that is, maintaining the status quo but with cleaner energy. However, they fail to address the underlying values and relationships that led us to this crisis in the first place. The relationships we have with our environment that lead us to fracking, massive strip mines, and clear cutting old growth forests doesn’t become less harmful just because we switch to using greener technology. Examining our actions as different types of relationships, it’s clear that we treat certain places and people who live in them as ‘disposable’, and that’s where the issue lies. In other words, the climate crisis won’t be solved by slapping solar panels on exploitation and injustice. We collectively need to examine how we view the environment—whether it’s something separate from us that we exploit at will, or as a relative that we care for and in turn it cares for us. I find inspiration and hope from my Indigenous siblings and the traditional ecological knowledge they have developed and refined over the millennia. Environmental relationships based on reciprocity are a common feature in many Indigenous cultures in the Americas and globally; it’s a concept that I’ve introduced to my students to help them imagine alternative and truly sustainable ways of living with our planet, and I believe [it] will enrich conversations about the climate in much needed ways.” —Zsea

Contributors:

Zsea Bowmani is a legal scholar and civil rights attorney working at the intersections of environment, race, gender, sexual orientation, human rights, and the law.

Liana DeMasi (they/them) is a freelance journalist, the LGBTQ+ Editor at OptOut, and an adjunct lecturer at City College of New York. You can find them on Twitter.

Isaias Hernandez is an environmental educator and the creator of QueerBrownVegan. They are currently working on their second business Citizen-T Project.

Ash Sanders is a writer, podcast producer, and climate activist in Brooklyn working on a book about the end of the world and an audio documentary about the water crisis in the western US. Read her essay on climate grief here.

Daisy Simmons is a freelance writer with 15 years’ experience sharing environmental stories, including for her new series Climate Personals at Yale Climate Connections.

Irene Vázquez is a Black Mexican American poet, journalist, and editor, currently based in Hoboken, NJ.