The Feeld Guide to Good Gossip

At the intersection of the political and personal lies gossip. When practised well, gossip is not just juicy—it can also be lifesaving.

Gossip as an act, in its broadest definition, is the exchange of information about absent third parties. When we think about gossip we often think about frivolity, untrustworthiness, or even spite. But the desire—sometimes the necessity—to talk about others has been with us since time immemorial, serving functions from strengthening bonds to warning others, to providing a warm dopamine boost as we indulge in some second-hand schadenfreude.

There’s no denying that the intimacy of the act, of being privy to information without the subject’s knowledge, feels good. Which is to say that being a gossip feels good, even if we also feel, perhaps, that it shouldn’t. Gossip can still be idle—that’s part of the fun! Gossip can be juicy, scandalous, irreverent. It can also be lifesaving.

Gossip’s evolution

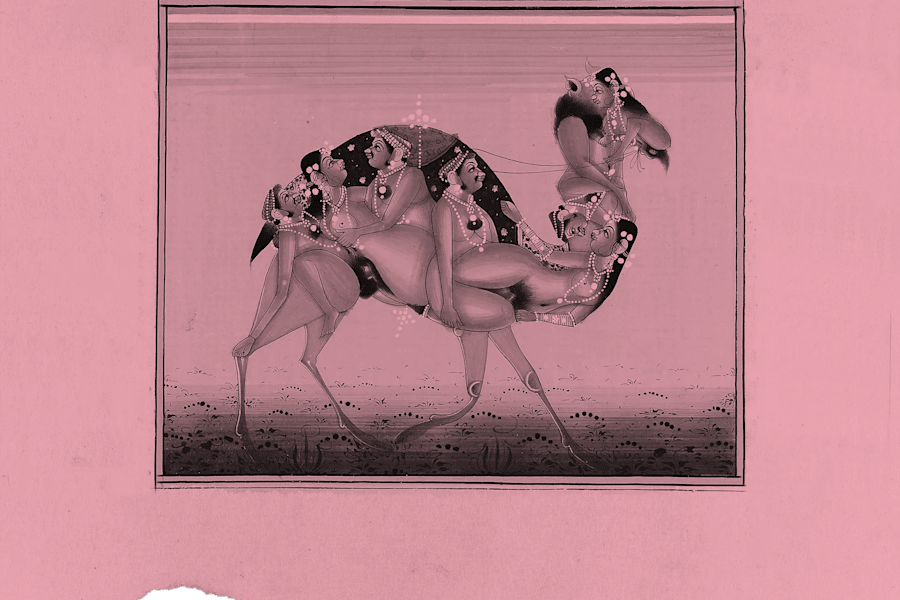

Gossip has been around in some form or another for thousands of years—recorded in the literature of Ancient Greece, spread around the markets of Mesopotamia, and woven into secret coded letters in Early Modern England, to give just a few examples. One theory of its evolution comes from anthropologist Robin Dunbar, who hypothesized in his 1996 book, Grooming, Gossip and the Evolution of Language, that gossip functions as a kind of language-based “social grooming.” Primates pick insects from each other’s fur as a way to bond and maintain community, releasing endorphins and spending quality time together in the process. To an extent, we also groom each other—but our communities are larger, and literal grooming is fairly inefficient. Enter gossiping—so the theory goes—as a way for humans to create and maintain bonds.

A study on “prosocial gossip”—gossip which shares negative judgments about a third party, but where the shared information has the potential to protect the recipient—showed a development between how three- and five-year-olds shared information. Three-year-olds would make recommendations to each other based on behavior, but without expressing the reason. By the age of five, children are starting to learn how to make judgements about people based on observations (for better or for worse)—and learning to share these judgments in the form of gossip. Gossip not only acts as a way to spread information, but sharing gossip is an act of trust.

What’s in a term?

The etymology of gossip is fascinating—steeped in misogyny, the changing place of women in society, and the encroach of capitalism. As feminist historian Silvia Federici, in her essay “On The Meaning of Gossip,” puts it: “Tracing the history of the words frequently used to define and degrade women is a necessary step if we are to understand how gender oppression functions and reproduces itself.”

“Gossip” as a noun originates from the Old English godsibb, which translates quite literally to godparent. Around the 1300s this term was extended to mean “familiar acquaintance,” with a specific emphasis on “women friends invited to attend a birth.” Gossips were invited into a birthing room to help support the mother—a space from which men were excluded, which piqued their curiosity. But by 1560, the meaning had changed to the more suspicious “anyone engaging in familiar or idle talk.” Not too long after the first change in meaning, gossip came to be defined in the 1620s as a verb: “to talk idly about the affairs of others.” And by 1811 gossip’s position had deteriorated further to mean “trifling talk, groundless rumour.” Over the course of a few hundred years, godsibb’s origin as a powerful, intimate term for friendship had changed into something altogether different: to the term, often with negative connotations, we recognize today.

Federici links the advent of this change to the social advent of capitalism, and a wider demotion of women’s social roles. But the time the meaning of the word had changed in the sixteenth century, so had the position of women—once more autonomous and close-knit with other women, now obliged to put obedience to husband and family first, amidst a devaluing of the communal labour of “women’s work.”

Gossip was a threat to the patriarchal order, for those unheard words in the birthing room, or over sewing or laundry, could undermine the authority of the husband. Punishments for gossiping included inventions such as the “scold’s bridle,” sometimes known as the “gossip’s bridle,” a contraption first used in 1567 which enclosed the head in a padlocked cage, with a painful spike at the tongue.

It’s chilling to track gossip’s change from a term celebrating close bonds, to something designed to remove the agency and legitimacy of information. Stripped of its original meaning it instead became gendered, negative, and a way to dismiss the talk of women as trivial at best, dangerously subversive at worst.

The power of gossip

Today we might mainly associate gossip with celebrity magazines, or juicy tidbits about people we know. (As an aside, apparently we’re so invested in celebrities and their mishaps because their ubiquitousness makes them feel like part of our social circle—the “parasocial hypothesis”).

But gossip can also motivate people to behave better, knowing they are being watched, their reputations at stake—or it can help people navigate the ethical and practical paths of life. As author Marlowe Granados puts it, “Gossip’s strongest power is how it gives examples of how other people live and act. Often, the person who is hearing new information will turn it over in their mind—‘How would I act in that situation?’ or ‘What would I do?’. In a way, it’s a little like reading a novel.” It can give us insight into how other people think and feel, and our own reactions—are we scandalised, intrigued, envious, or supportive?—can also provide us with insight into ourselves.

Gossip can also be a vital form of information-gathering, protecting, and warning. It can hold harmful individuals accountable. The prosocial gossip earlier described can be a way for people to share knowledge of dangerous individuals and situations. Just think back to #MeToo, where the sheer number of people sharing their experiences of harassment and assault from men in power, taking stories quietly shared in private spaces to public networks, became a tipping point. What had previously been dismissed as gossip became a driving force for justice.

But long before #MeToo, we’ve always shared stories of individuals in order to protect others; the boss who only promotes male colleagues, the uncomfortable date, the lying friend, the man who assaulted an acquaintance. Gossip can be a protective act of resistance and of solidarity.

Federici notes that “gossip” is contextual, and that “women have historically been seen as the weavers of memory—those who keep alive the voices of the past and the histories of the communities, who transmit them to the future generations and, in so doing, create a collective identity and profound sense of cohesion. They are also those who hand down acquired knowledges and wisdoms—concerning medical remedies, the problems of the heart, and the understanding of human behavior.” By reducing these forms of communication to the debased or treacherous, a whole tradition is devalued.

Being a good gossip

What does being the recipient of gossip say about you? Gossiping well is a skill and an art; knowing what information to share, who to share it with, and what to keep quiet. I know my ears prick up when the possibility of good gossip is on the horizon. But part of the appeal of receiving gossip is the thrill of being confided in in the first place. It means I’ve been picked as someone trustworthy, someone who will engage in and appreciate the gossip.

Good gossiping is useful, not malicious. It doesn’t set out to hurt unnecessarily, or spread falsehoods. Good gossip can shame, but it can motivate too. It can bring us closer to others, and closer to ourselves: our own moral compasses, our own distinction of right from wrong, with the possibility to expand our empathy. As well as an excuse to pass a little judgment—as a treat.