Metamorphosis: A chronicle of offline transness

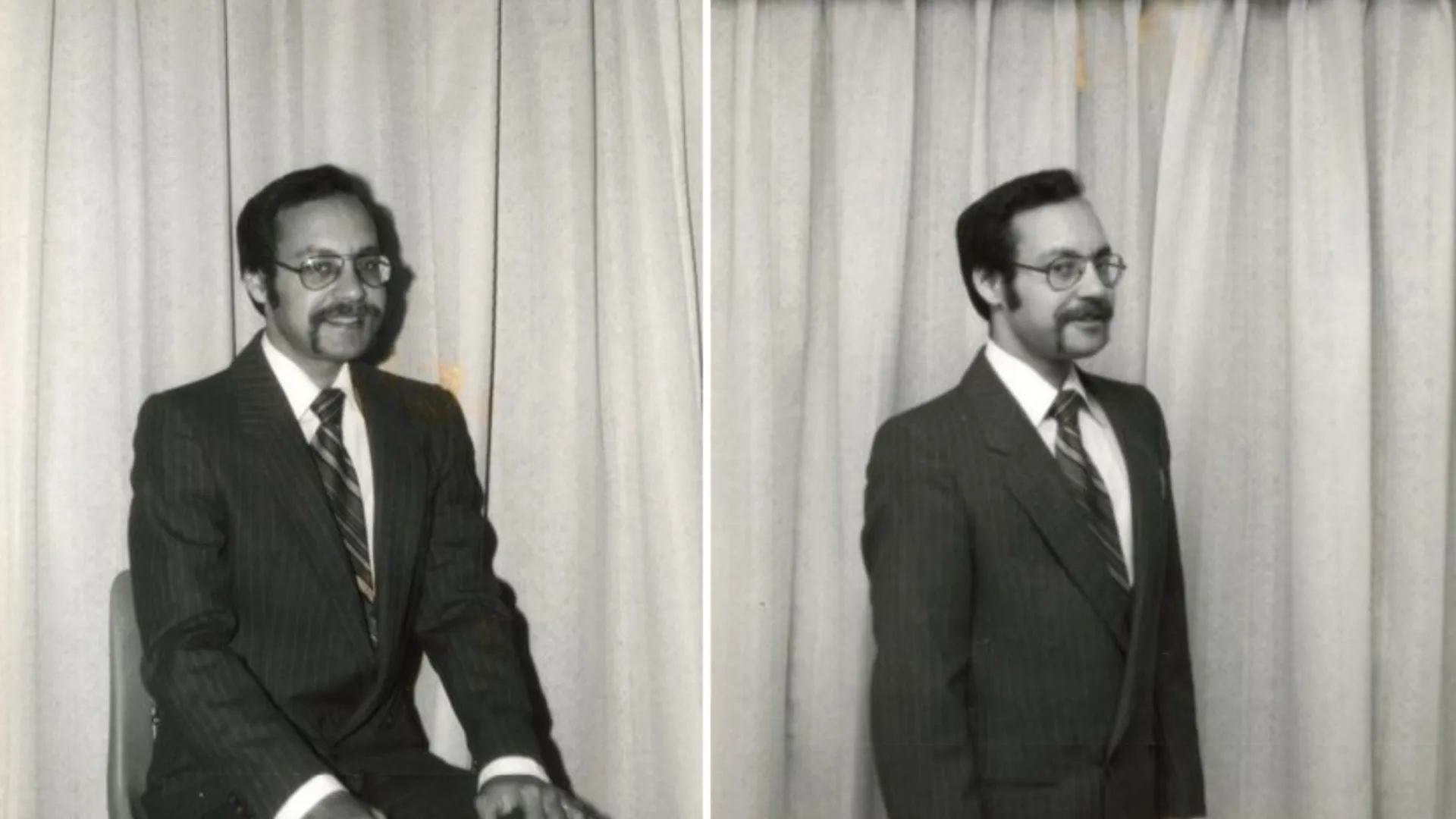

"Black and White Photographs of Rupert Raj." Photograph. Digital Transgender Archive, https://www.digitaltransgenderarchive.net/files/70795807n

Sometimes looking back can show us a way forward. Rupert Raj and Lou Sullivan’s newsletter exchange network acts as a model for how, in increasingly treacherous times, the trans community can find safety in each other IRL.

Rupert Raj looked good in a suit; Rupert Raj looked like a normal guy at a bar; Rupert Raj looked like an emblem of his age, or, at least, the moment the photo was taken, 1988: the oversized glasses, wide lapels, brown striped shirt with beige jacket, chest hair out, chain, the handlebar mustache made famous by Tom Selleck in Magnum, P.I., in which the actor, while living in an abandoned Hawaiian estate, sometimes solves a “crime.” A mustache can be a suit for the face. In the photo, Raj––born in Ontario, Canada––is thirty-six. His American protégé, Lou Sullivan, will die three years later, from AIDS-related complications, at thirty-nine years old.

This was meant to be an essay about Sullivan––the community organizer and die-hard Beatles fan widely known as America’s first out gay trans man. Sullivan’s life was reintroduced to trans audiences with the 2019 publication of We Both Laughed in Pleasure, an edited version of his diaries, which he started writing as a Milwaukee child.

This hypothetical essay would, I imagined, delve into the social milieu of Sullivan’s FTM newsletters. First launched in 1987, these newsletters were an extension of Sullivan’s in-person “FTM Get-Togethers,” hosted in San Francisco, where he lived. These events offered a combination of healthcare information, political education, and hanging out. Lou developed the FTM Get-Together concept, with its corresponding newsletters, through his long-term friendship with Rupert Raj.

In the end, it didn’t make sense to look at Raj and Sullivan separately. History, intentionally and incidentally, due to factors of empire, race, and coincidence, has tended to separate them already; such factors have also, of course, contributed to how, and to what extent, each one has been recognized. I’ve known about Sullivan since 2018. I found out about Raj this July.

The other reason to look at Sullivan and Raj in tandem is that it more accurately reflects North American trans cultural production and life right before the internet. When Web 2.0 launched circa 2004, geographically isolated trans people began finding one another online and, eventually, in person. But since trans people have existed forever, they have obviously existed—and found one another—before the internet. As scholar Avery Dame-Griff points out, “Gender community–specific periodicals had been in circulation throughout the 1960s and 1970s, and an extensive national newsletter exchange network emerged in the mid-1980s.”

Raj and Sullivan helped build this “newsletter exchange network,” knitting interpersonal, movement bonds long before digitization.

Gender Review Issue 1, published in June 1978 by the Foundation for the Advancement of Canadian Transsexuals (FACT) features three topless photos of the foundation’s “President & Editor, Nicholas C. Ghosh,” the then-chosen name of Rupert Raj. In most other contexts, this wouldn’t make sense; but for a 1970s FTM newsletter, showing Raj’s flat, male chest, hair from the sternum down, was proof of concept. He passes. You can pass. Maybe you already do.

Looking at these photos now, it’s hard not to wonder who took them, and why. In the first image, Raj looks uncomfortable and sexy. In the last one, he’s about to speak. He wears a gold medallion. He is twenty-six.

Rupert’s father, Amal Chandra Ghosh, was an Indian nuclear physicist; he met Rupert’s Polish mother while working at Stockholm’s Nobel Institute for Physics. Rupert was born in Ottawa in 1952, the same year Christine Jorgensen, “G.I. Joe Turned G.I. Jane,” announced her medical transition to the American media. But while the press tour and book royalties enabled Jorgensen to sort of make a living (while her public transness blocked her from getting any other job), a single media spectacle hardly amounted to basic, widespread, actionable information about medical transition. “Growing up,” says Raj in an interview, “I didn’t know the word ‘transsexual.’ I thought I was the only person on the planet like me.”

At sixteen, Raj’s parents were killed in a car accident; two years later, he went to the Royal Ottawa psychiatric hospital and said that he’d commit suicide if they didn’t help him medically transition.

While this was not an uncommon tactic, we can also understand why Raj––who could have easily been barred from the then-dominant university gender clinic system––felt he had no choice. In the 1950s, legal trans healthcare was almost non-existent in North America. Jorgensen had gone to Denmark for a reason. But in 1966, Harry Benjamin, Jorgensen’s endocrinologist, published The Transsexual Phenomenon; instead of treating gender dysphoria as mental illness, Benjamin classified it as a physical problem, which, like cystic fibrosis or leukemia, could be treated medically. With the possibility of manipulating gender now on the table, university clinics were suddenly very interested in funding trans healthcare––as was the federal government.

The result, as scholar Susan Stryker writes in Transgender History, is that “access to transsexual medical services thus became entangled with a socially conservative attempt to maintain traditional gender configurations in which changing sex was grudgingly permitted for the few seeking to do so, to the extent that the practice did not trouble the gender binary for the many.” Raj, who was neither straight nor white, was not an ideal candidate for this system of gender management. Since no one in Canada would administer testosterone, he was eventually treated at Harry Benjamin’s private Manhattan clinic.

FACT thus emerged from Raj’s successful but laborious medical transition, and from his desire to create some of the medical infrastructure that he wished he’d had. In Gender Review Issue 1, a section titled “Foundation History,” explains that “besides lobbying for political reform of sex laws within Canada, FACT aims to educate the public on the often confusing subject of ‘gender dysphoria’ (here = transsexualism) through the lending out of its TS library books, [and] distribution of its publications… For TS inquirers and relatives, we provide information, counselling and referral services free-of-charge.” The front page section, titled “TRANSSEXUAL OPPRESSION!,” explains that “newly appointed FACT director” Inge Stephens, fired after her trans status was revealed, “is planning to fight in an upcoming court trial… She and her lawyer… feel confident in winning and thus, establishing a precedent.”

Looking back, it is hard to tell what is scene incest, friends booking friends, and what is merely a reflection of how relatively small trans culture and healthcare were in North America at the time. Page 3 of the newsletter begins with “a tribute of thanks to the following gender specialists,” the first of which is Harry Benjamin, who, in addition to treating Raj, was also Jorgensen’s doctor.

The “Tribute” section, like most of Gender Review, also doubles as a practical Roladex: “specialists” are listed by name, address, and surgical specialization, as if encouraging readers to book a consultation. A segment called “Of Interest to FTS Fellows” recommends using “a man’s rib supporter (for support of broken ribs)... as a breast binder.”

Instead of separating need and desire, as if they could ever be split apart, Gender Review’s very layout puts them next to one another. Raj’s profile is wedged between a coupon for detachable facial hair pieces, sold by a company called Masculiner, and an advice column, “Kyle & Karol’s Korner,” in which a Ms. J.J.R. describes being “romantically and sexually attracted to another teller in the bank where I work.”

In 1979, Rupert Raj began corresponding with Lou Sullivan, who had just started testosterone.

Gender Review folded in 1982. It didn’t matter. In 1981, Raj had founded the Metamorphosis Medical Research Foundation (MMRF), which provided medical research and resources exclusively for trans men. In 1982, Raj, seemingly addicted to small-circulation printed matter, started MMRF’s newsletter, Metamorphosis, a “bimonthly newsletter exclusively for females-to-males and professionals.”

While Gender Review was almost zine-like in terms of style and tone, Metamorphosis focused less on politically justifying trans healthcare and more on materially accessing it. In “Rupert Raj and the Rise of Transsexual Consumer Activism in the 1980s,” scholar Nicholas Matte describes the assimilationist aspects of this pivot. He argues that Raj’s Metamorphosis tried to “conceptualize transsexuals as a medical/patient-consumer group,” yet another valuable niche market within a neoliberalizing economy.

But as Matte also points out, both Metamorphosis and MMRF unflaggingly worked to un-gatekeep trans healthcare, redistributing expertise and resources in the face of a crumbling university gender clinic system. As the Cold War era of federally-funded scientific investment and research came to a close, the Johns Hopkins Gender Identity Clinic, the first in the U.S. to offer gender-affirming surgery, would shutter in 1979. When Raj began publishing Metamorphosis in the early eighties, the Canadian healthcare system required trans people to be psychiatrically hospitalized as part of the HRT-approval process; multi-year wait lists barred most people from even starting it in the first place.

In what feels like the premise to a medical slapstick or a steampunk porn, Raj even tried to develop his own prosthetic penis circa 1985, meeting up with a dildo manufacturer in New York. The goal was to make something that would work for both urination and sex. When given an experimental prototype, Raj reported on it for Metamorphosis readers. The result, as Matte demurely puts it, was that the prosthetic penis “was not sturdy enough to suit their purposes.”

In a 1986 letter to Raj, penned the same year he started hosting his “FTM Get-Togethers,” Sullivan would write, “I really like the magazine format of Metamorphosis. Thanks for forging ahead with the publication and keeping it together for us.” The letter is written in blue pen on lined white notebook paper, the letters slanting from left to right.

Even after Sullivan’s death in 1991, FTM continued to be one of the most widely used and respected practical sources on how to live as a transsexual man throughout the 1990s.

Together, through their newsletters and in-person social gatherings, Rupert Raj and Lou Sullivan connected geographically isolated trans people across North America. As the university gender clinic shrunk and trans healthcare privatized, Gender Review, FTM, and Metamorphosis circulated medical knowledge and services. People transitioned who wouldn’t have done so otherwise. We often credit the internet for inventing this kind of community infrastructure; we’re wrong.

As algorithmic suppression, anti-trans legislation, and healthcare austerity worsen, Raj and Sullivan’s newsletter and in-person meetings—where you could discuss things that couldn’t be talked about over the phone—provide a helpful historical model for offline trans culture, organizing, and life.