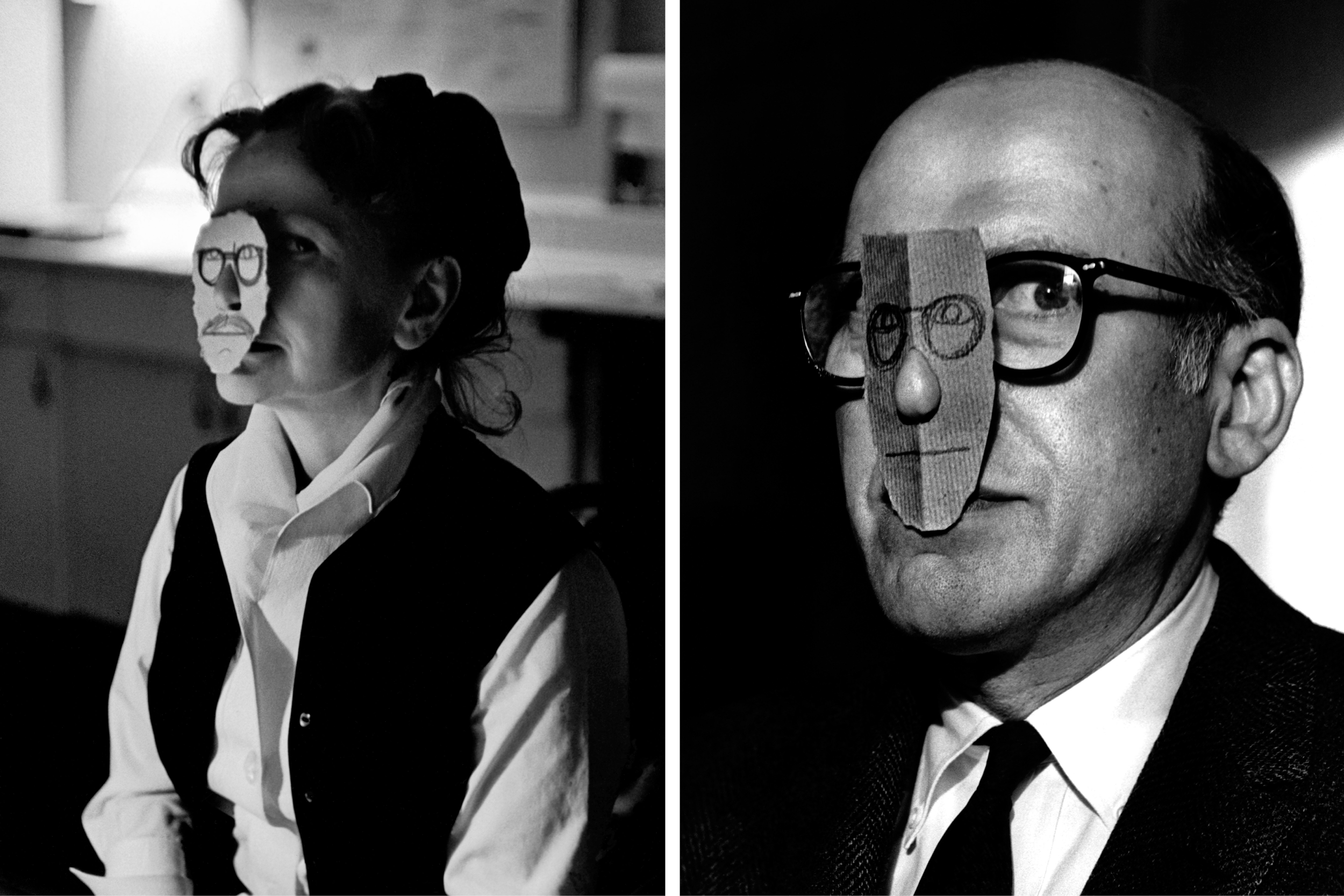

Photographs by Inge Morath © /Magnum Photos. Mask by Saul Steinberg © The Saul Steinberg Foundation/ARS, NY.

Evenings with Saul Steinberg and Hedda Sterne

Saul Steinberg is about forty-five. He is of medium height, well-proportioned, with a good physique. His hands are well-formed and rather large, and don't receive any special attention. The famous face we all know. If we have not seen photographs in old copies of Vogue, we would recognize it from his drawings of the anonymous man: a long oval, with a large nose, heavy glasses, and a fat, ginger-colored moustache, creating features a little like one of those fake rubber noses complete with spectacles and curving moustaches that children buy from a tricks dealer. He is bald but was once blond. His eyes are sharp, brilliant, unkind. I cannot remember their color, I only recall that they fix on you aggressively. He dresses in his own style, wearing knit jerseys at home, black or wine colored, with a turtle neck, or shirt and vest. His suits were dark and possibly Italian. They would have been of fine quality but were not in the accepted “Eastern” mode. If he had such clothes I imagine he would have made a joke when he bought them and made another when he wore them, but that such things would have soon bored him, like the painted ties with nudes and racehorses he admires for their vulgar vitality, which he would not wear outside his house. Once I saw him on Fifth Avenue wearing a tan summer suit and a straw hat; he was then indistinguishable from everyone else, a prosperous businessman, which indeed he is.

His verbal humor is fantastic, delighting in plays on words, mispronunciations, and bombastic phrases picked up from the newspapers or invented by himself. It is not usually directed maliciously but it can flash to a target. There are many allusions to literature and to non-literature: the funny papers or advertisements or people's jokes he hears. French, Yiddish, and Italian idioms appear. It takes private turns with, to me, secret or cryptic references; there are sudden leaps and shifts which I can't follow. He and his wife are quick to create theories, usually artistic ones, upon interesting chance discoveries, generalizing rapidly and with great cleverness. These may be taken seriously at the time but are seldom alluded to again. Occasionally he builds and builds upon one, and then some transformation of this thought will appear in a drawing.

Though I have been to his house often during the time we were working together on a film, and at all hours, I have no certain knowledge of how his days are spent. Since he asks not to be called up before ten I imagine he's not an early riser; Perhaps he works a little before lunch or going out. Lunch is about one and there are often guests. The afternoon is spent in his workroom, sometimes drawing, and sometimes reclining on top of a low built-in cabinet which is padded and into which he exactly fits. Here he reads. The books tend to be novels, are apt to be in French, and seem to be in advance of usual tastes—rather obscure, of philosophical or psychological interest, to judge from reviews of the English translations which appear in TheNew Yorker and TheNation some months later. He recommended some of them, but I never read any. Then, as now, another person's discoveries in books have to wait until after my own, and by then I've forgotten them. About four-thirty or five he descends to a wonderful tea in his combination kitchen and dining room. There will be real brewed tea and some kind of cake, or bread and butter. He and his wife are then very animated, unless he's coming down with a cold. He's slightly hypochondriacal. I say “slightly,” comparing him with myself, but I don't know what morbid fears he succumbs to in private. After his tea he goes back upstairs and continues to work until it is time to have dinner, or to get ready to go out. I imagine here and there he naps a bit, like anyone who sets his own schedule.

Photograph by Inge Morath © /Magnum Photos. Mask by Saul Steinberg © The Saul Steinberg Foundation/ARS, NY.

Dinners are both interesting and delicious, for Hedda Sterne is a superb cook and their house is a gathering place for other well-known people. These tend first to be New Yorker writers— Anthony West, Janet Flanner, Niccolo Tucci. There might be someone really famous like Alexander Calder or Joan Miró. One night John Betjeman was there. Or there will be old friends, like Betty Parsons, Saul and Hedda's dealer. There will be a new face or two, an architect or a painter, or perhaps the friend of a friend, brought along at the last minute. There is nearly always someone who has just arrived in New York on a transatlantic flight who is feeling groggy.

The most famous guests tend to be seated around Saul; Hedda sits with her back to the cooking stove, which is bright red, at the middle of the table, from where she can jump up to bring things. Then, at the other end, are the wives of the well-known men, who are sometimes not as clever and who tend to be disregarded slightly and who sometimes become quarrelsome. I am usually seated with these women. The first time I was invited it was like that, and I was immediately eager to take part in the conversation at the other end of the table, as it soon occurred to me that in Hedda's placement I had been put, as an unknown quantity, where I could do the least harm conversationally. But I was not to be undone, and put forward some bright comment, or reference, in a loud voice. All the great faces swivelled in my direction, astonished that this unknown youth had piped-up. They could not have been more astonished if Hedda's cat had spoken.

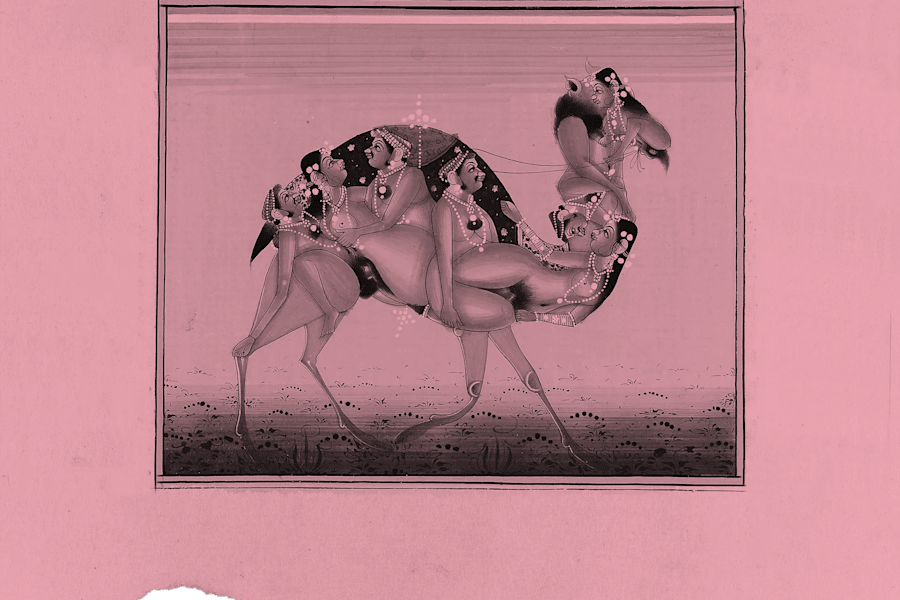

There is always a great deal to drink, no one leaves before midnight, and it is the neglected wives who always break up the party. Sometimes there are funny masks, or sessions with hula hoops. Someone has brought a box of color slides which are held up to the light and get dropped onto the butter on their way around the table. This table is long and oval shaped and can seat twenty, with an overhead light on a long cord. The chairs are all bent wood, highly polished. All about are strange works of art—strange in that they do not reflect a “cultured” taste so much as a rarified interest in the peculiar, the undefinable. There are constructions, mazes, painted stones, a canvas by Magritte, drawings by Giacometti, a life-size plaster woman with her arms outstretched and a red silk shawl tied around her middle. There is a precious folded drawing in which Steinberg and Picasso have taken turns to make a grotesque and even obscene-looking anatomy. These things merge with a collection of toys—rabbits striking cymbals, magnets, a painted cat in a basket, a music box which plays enormous discs, an Eames plastic chair without legs, sitting in a corner like some Daliesque organ, faintly sinister.

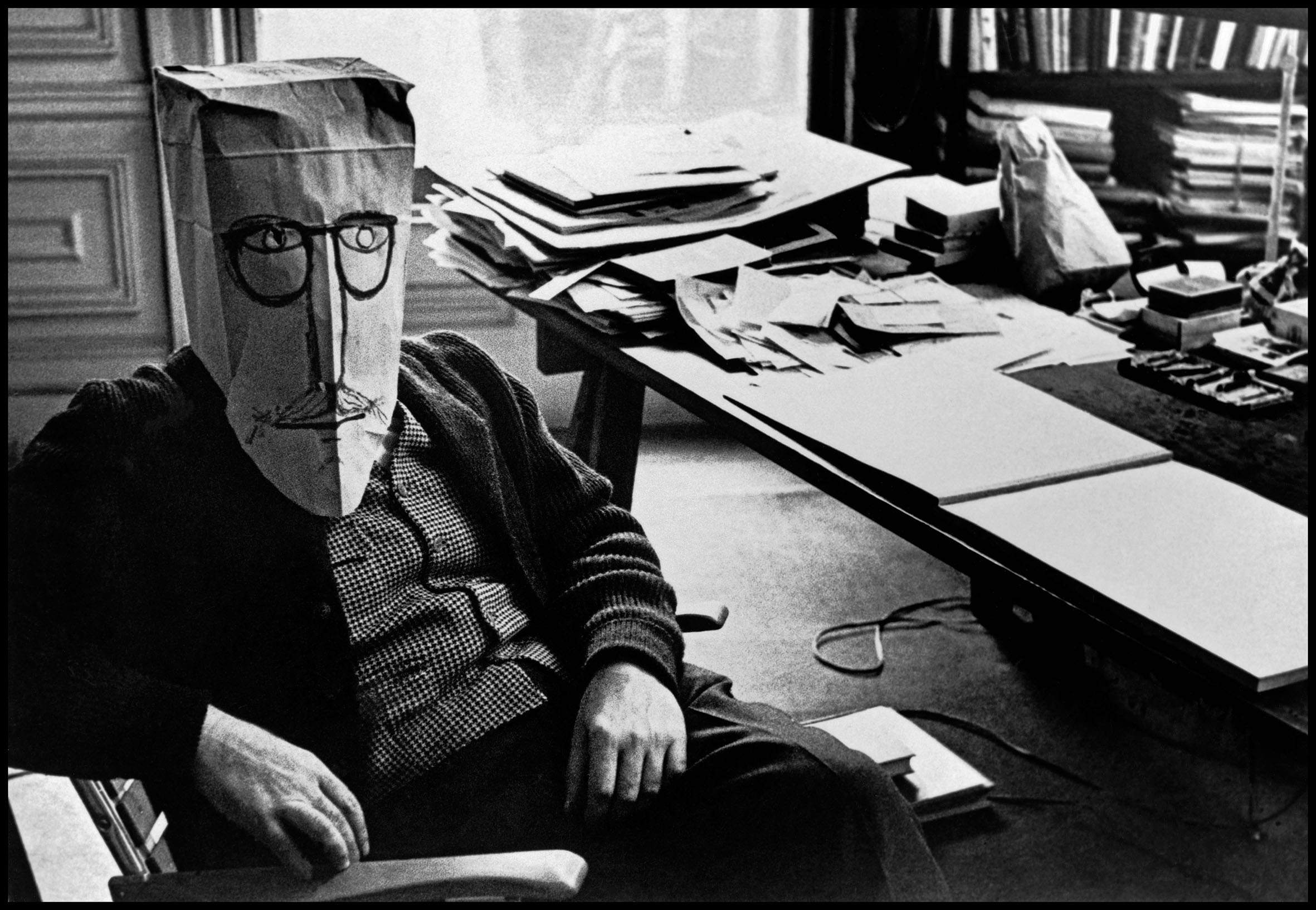

Photograph by Inge Morath © /Magnum Photos. Mask by Saul Steinberg © The Saul Steinberg Foundation/ARS, NY.

Through all this Hedda Sterne hops like a bird, from her perch in front of the oven to her chair and back again, eyes bright, head cocked, got up in some outlandish and delightful costume, perhaps a ski outfit, complete with parka, and always with a kind of large bow in her hair like an old-fashioned maid's cap. Her sweet face is that of the eternal woman which appears in her husband's drawings, sometimes coquette, sometimes cat, sometimes little girl, always dreaming and secret. But it is a face which is beginning to reflect a private sorrow, and Steinberg's sharp remarks, which are not private, and which reveal some great impatience, send her shouting and furious up the winding stairs to her studio. He is said to be a philanderer; he is certainly gone a great deal of the time.

The house they live in is on East 71st Street between Lexington and Third Avenue. It is a red brick duplex and must have been built in the early twenties. The Steinbergs have the right half and a garden behind. There are two rooms on the first floor, two on the second—this is his domain—and several more on the third, where I've never been. His drawings are stuffed into several big cabinets in no particular order; some of them are torn and bedraggled. From these I pulled out dozens of his American drawings, which were to be the subject of our film, a trip across the country, starting in New York and ending up in Southern California. I found all sorts of things when I went through the flat drawers of his cabinets, which he had been looking for: old letters, photographs, documents, photostats, a rather cruel Christmas card from Cartier-Bresson with a photograph of a fat, tired old woman. The room which overlooks the street has a billiard table in it—Steinberg enjoys billiards and poker—and contains two collections, one of small, porcelain nude women in various abandoned poses, and another of tiny bronze busts of important, forgotten men: generals, Kaisers, composers, archdukes with goateed little faces and puffed-out bemedalled chests.

This was written sometime in the early sixties.

We worked together all through early 1959 on our film. I would gather up a few of his drawings and take them to my apartment on East 80th Street, where I would light and photograph them, using a 16-mm Bolex camera. Some drawings were quite large; others he hadn't looked at in years. I took an editing room near Times Square and tried to cut the footage together. But it was far less effective than the drawings he'd made of Venice that I'd used in my first film, Venice: Theme and Variations. For the Steinberg car trip across the United States I wanted Saul to actually draw for my camera; I wanted to see up close the ink flowing from his pens, and those new images building up. But he nixed this idea, saying it would be boring for him if he had to do that.

In the fall of 1959 I left for India, where I stayed a year, with the summer of 1960 being spent in Kabul, Afghanistan. When I returned to New York, Saul had left his home on East 71st Street, and had left Hedda. I called her and she invited me to dinner, telling me to bring anything I had to show her what I'd been doing in India. I did take a great many photographs which I'd gotten printed up nicely in New Delhi, so I brought those. There was one other guest at dinner, and to my horror it was Cartier-Bresson, whom I would be meeting for the first time. How could I show Hedda my Indian and Afghan pictures in front of the most famous photographer in the world? Gamely, I did, and he politely flicked his eye over them as Hedda enthused.

Four or five years later at a party in the Hamptons I met Saul again. During this—the last conversation we were to have—he told me he regretted his unwillingness to draw for my camera. It might have been interesting, he said.