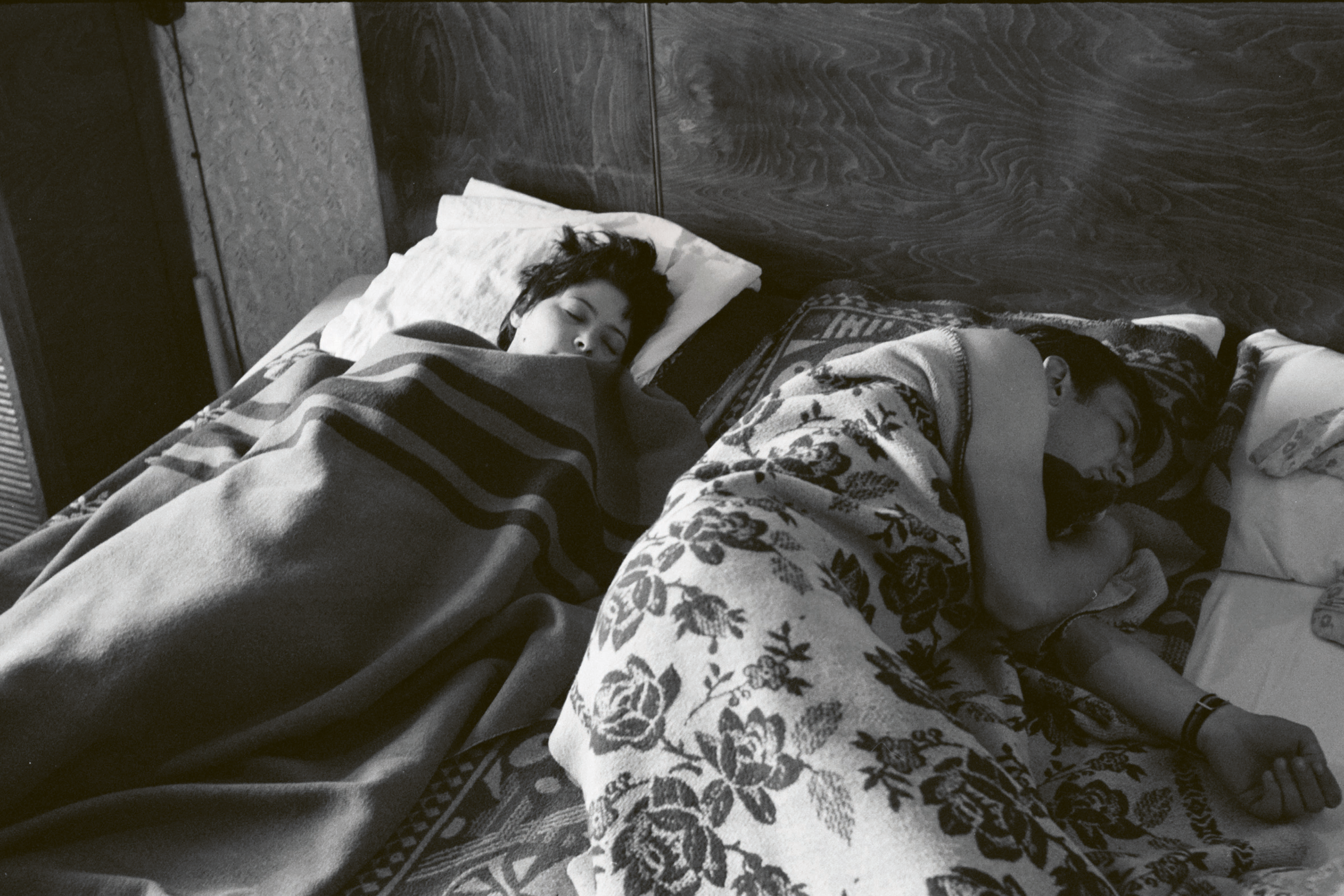

Source: Bulgarian Visual Archive / Paraskev Andrekov

Capitalism came simultaneously with my first orgasm. It was the early 1990s and I was an innocent, unsuspecting middle-school kid, confined with my innocent, unsuspecting parents in a pre-fab concrete apartment block in Sofia, Bulgaria. Like all such apartment blocks in the neighborhood, it resembled a residential tombstone. We were all living under a rock. But “the Changes”—the events that followed the demise of communist regimes across Eastern Europe in late 1989—were already underway. Old-fashioned beliefs and proprieties were getting quickly discarded. When the Iron Curtain came down, it revealed a pile of naked bodies, copulating in all kinds of inconceivable positions. Pornography you may say, was one of Bulgaria’s first casual encounters with political freedom. I had, of course, chanced upon erotic materials before: my grandfather’s worn-out deck of playing cards with photos of women in negligée on the flipside; a glossy WestGerman home-shopping catalogue, Neckermann, that among furniture and clothes and camping gear offered glimpses of flimsy lingerie and sex toys. The latter was the Holy Bible in communist Bulgaria, shaping the dreams and desires of several generations, oftentimes smuggled in across the border by sailors or long-haul truck drivers. It was certainly more enticing than the hardback collected works of Marx and Engels, and a more effective propaganda tool than any speech by Reagan or Thatcher.

With the collapse of the old order what was a trickle turned into a flood. A cheaply printed weekly newspaper, Chuk Chuk [Knock-Knock], introduced hard-core pornography to the newsstand—no black plastic wrapping or age restrictions on customers. An intrepid classmate of mine would regularly bring a copy to school for us to gawk at. Cable TV, a novelty, streamed porn freely after midnight on Scandinavian movie channels and I’d pre-program the VCR in our living room to secretly record those nightly pleasures for next day’s enjoyment. Advertising of every imaginable product, from cars to beer to bubble-gum, featured unabashedly objectified female bodies. At any dance party the official attire was maximum nudity. “If I get my hands on you, I’m gonna rip your panties,” went a famous local song at the time. Sex was the most popular distraction as the economy was getting fucked by mafia bosses and free-market politicians.

Bulgaria’s liberated libido sometimes ventured beyond the orgiastic, commodified, heteronormative gaze. Though cautiously at the beginning, in secluded underground bars with buzzers on unmarked doors, gay men and women who had been ostracized by the communist regime began to form their own communities. Theaters put on radical performances of plays by provocateurs such as Jean Genet and Eve Ensler, among others. Explicit writing about sex in various configurations entered the poetry and novels of local writers. Michel Foucault and Simone de Beauvoir appeared on the shelves of bookstores for the first time. A sexual revolution, if woefully belated, swept through the minds and bodies of Bulgarians, toppling the prudishness of the proletariat.

On June 28, 1986, at the tail-end of the Cold War era, a group of American and Soviet women took part in a “tele-bridge,” an early form of teleconferencing, to discuss various issues related to their daily lives. It was a way to thaw relations between the two countries by having ordinary citizens talk directly to each other. During the debate, one of the American participants posed a question: “Television commercials have a lot to do with sex in our country. Do you have commercials on the television?” The reply from the other side was rather curious. “We have no sex and we’re strictly opposed to it,” said a Soviet woman. Amid the ensuing laughter and applause, she corrected herself, utterly embarrassed: “We have no sex—we have love.” At that point, another Soviet participant decided to chime in: “We do have sex. We don’t have commercials!”

I often think back to that slightly ludicrous exchange when foreign friends ask me to explain what it was like to talk about sex in socialist Bulgaria, “the closest satellite of the Soviet Union.” To put it simply, there wasn’t much of it—by which I mean conversation, not sexual intercourse. When the regime took over the country in a coup d’état toward the end of World War Two, in 1944, it envisioned discarding bourgeois norms of behavior in all spheres of life, including gender relations. Engels had criticized marriage as a micro-model of class antagonism and exploitation, in which women were treated as private property, passive objects in a system of exchange. Communism, he reasoned, would remedy that by creating a classless society, where both men and women stood on equal ground and formed novel kinds of romantic relationships, free of economic and religious oppression. Bourgeois marriage and its attendant models of forced monogamy would give way to proletarian manifestations of sexual behavior—even if monogamous again—based on some utopian notion of true love.

None of that came to pass. If anything, the Bulgarian Communist Party injected a more malignant strand of moral conservatism into public life, for interpersonal relations were now the exclusive purview of the state. Individualism was frowned upon, and what was more individual and private than sex? Of course, every society, religious or secular, exerts control over the personal life of its subjects, creating a set of disciplining discourses, but the communists were especially adamant about it, overeager to act as “the engineers of the human soul.” Or as the Bulgarian cultural anthropologist Ivaylo Dichev memorably put it: “Who better than comrade Stalin knows that love always involves a threesome [a man, a woman, and the state].”

Sex, on its own terms, couldn’t be inscribed within a teleological narrative of progress and the inevitable march of history that Marxism envisioned; it was too subversive and anarchic, beyond the moderating and modifying reach of the collective. It suggested that there is something in human behavior deeply rooted in biology, the subconscious, and personal quirks, rather than in material conditions. Sex was an instrument for procreation and the procurement of new laboring masses for the socialist state, and when it involved pleasure, it was solely acceptable within the monogamous, heterosexual structure of the family, “the smallest unit of society,” as the ideological cliché of the time called it. To engage in sexual desire for its own sake was officially considered “moral decay,” “depravity,” “licentiousness,” “dissolute life,” “parasitism.” It was akin to a crime against the motherland and its socialist values, a betrayal of one’s country.

In fact, in the early days of the communist regime people in Bulgaria accused of such sins were often dispatched for reeducation to labor camps or had to undergo public shaming in front of their neighborhood councils. Women who gave birth outside of wedlock carried a horrendous social stigma and were often compelled to abandon their kids in orphanages. Even schoolgirls who dared to wear skirts a tad too short were openly harassed by educators, their thighs branded with a special ink stamp. The Church and the Communist Party were not that different from each other after all.

Literature from that period was just as dogmatic, full of preposterous romantic situations and patriarchal boilerplates. It often involved a proletarian hero, exuding virility and mechanical knowhow, and a bashful, but ideologically committed “virgin.” Of course, love of party and country would have to come first for both of them, and their own love would be sealed only with social approval. Sometimes, the hero would be a sturdy peasant, plowing the land or working at the collective farm, and the heroine a simple village woman, full of uncountable virtues. There would be a kiss, then a fade out, and voila—children. On the rare occasions when writers ventured into the realm of the erotic it was usually to highlight the dangers of seduction that the darker, foreign, bourgeois “whore” presented to the class consciousness of proletarian men.

The novel Tobacco by the Bulgarian writer Dimitar Dimov, first published in 1951, is a famous case in point. It follows the rise and fall of a ruthless tobacco magnate, Boris, in the years preceding World War Two. Dimov tried to stick to the rules of socialist realism, offering a pointed critique of the pitfalls of the profit motive and the moral degradation it entails, yet his depictions of extramarital sexual relations were seen as scandalous by conservative communist critics at the time. Irina, the main heroine who starts out as a romantic, but ends up using sex as a tool for social advancement, was seen as particularly problematic. “In Dimov's characters, love does not manifest itself as a pure and noble feeling... but as a dark force, as eternal biological dissatisfaction,” one particularly vicious critic, Pantalay Zarev, wrote about the novel in the official press. “Eroticism is a tool of bourgeois literature to dull the minds of the masses, to distract them, to divert their attention from a proper understanding of socialist conflicts.”

In the end, Dimov was forced to write an extra 260 pages to make his book more ideologically palatable and silence his critics. He also added another female character, Lila, who was а virtuous communist fighter willing to sacrifice erotic love for the greater cause of social justice—a counterpoint to the fallen Irina. The female body had to be armed to be sexually disarmed.

It is true that the Bulgarian communist regime was the first to grant women voting rights and open up professional opportunities that hitherto had been denied to them. They could now be factory workers, tractor drivers, road builders, and even miners, engaging in the same labor-intensive work previously reserved for men, although management positions or high political ones were the rare exceptions. But even if they were “de-feminized” for the purposes of industry and the revolutionary struggle, in the private sphere they continued to live within highly patriarchal structures that were in their essence not that much different from those which had predominated in the previous era of village life. They had to behave modestly and dress appropriately, take care of their looks, while taking care of children, shopping, and general household duties. As for female sexual desire, that was dangerous territory, a no-go zone full of barbed wire and mine-fields. It was a taboo topic not only in public but within the family as well, where shame ruled supreme. The only space where women could legitimately have sex was marriage and even there the tacit disposition was to provide pleasure to men.

In 1979, two years before I was born, a most unexpected book appeared in Bulgaria. It was titled Man and Woman Intimately by the East German sexologist and psychotherapist Siegfried Schnabl. It had originally come out in German a decade earlier, during the heyday of the sexual revolution in the West, and had ended up selling millions of copies all across the Soviet Bloc, undergoing over a dozen editions. When the Bulgarian translation was published, it turned into a cult object, a rogue addition to every home library, right next to the equally popular but less enticing volumes like Our Kitchen and Tips of the Household Handyman. The cover presented a drawing of a naked man and a naked woman in an amorous embrace, about to kiss, the bulk of their bodies shielded by a giant fig leaf, which they held like an escutcheon in front of them. The more prudish Bulgarian families would often wrap the book in a newspaper jacket. Sex was still shameful, even if there was now an official book about it.

“My curiosity in my early teenage years prompted me one day to reach for this book, which I noticed on the black metal shelf, typical of the late socialist period, and thus began my literacy about intimate relations between women and men,” a friend of mine, Milena Filipova, recalled. Another friend, Vladislav Hristov, told me a similar story of how he and his cousin first discovered Man and Woman Intimately. “He was 12 and I was 10,” Vladislav wrote to me in a personal message, after I put out a call on Facebook for people to share their memories of Schnabl’s book for this essay. “We were alone in his family’s living room, when he climbed onto one of the tall shelves of their library and took down this book. With a proud look of victory and a sparkle in his eyes, he explained to me, ‘Look how they [his parents] tried to hide it—they placed it with the spine inwards so I wouldn't find it.’ And so we immersed ourselves in the pages of the book, staring at the illustrations and drawings of sexual acts and women's private parts.”

Man and Woman Intimately initiated a frank conversation about sex as nothing before had done in Bulgaria. Though on the surface just a primer in sex-ed, it grew into a cultural phenomenon, a how-to guide to erotic pleasure, a self-help book on sexual dysfunctions, an introduction to marriage counseling, a dictionary of “deviations,” as well as a masturbatory aid for sex-starved adolescents, who got turned on even by medical diagrams of genitalia and cross-sections of coitus (like my friend Vladislav and his cousin). “Man and hand intimately,” was an oft-quoted Bulgarian rhyming pun of the title of the book.

Even today, Man and Woman Intimately reads like a revolutionary tract. “Satisfied love—which includes sexual satisfaction—is an essential element in the development of human personality and an iteration of human existence,” the author writes in the first section of the book, proclaiming his thesis from the rooftops amid the silence of the socialist camp. After a hasty biology lesson on the basics of cell division, the function of hormones, and the structure of human genitalia, Schnabl jumps right into revolutionary rhetoric. Female desire has been sidelined for far too long and that needs to change; for far too long societies have been guilty of implementing “a double morality” toward the sexuality of women. “Just as men, women have the right to sexual satisfaction. During the love act she is also allowed to ask for her own desires to be satisfied,” he writes and continues in a sort of paean. “How many women consciously or unconsciously suppress these new-budding impulses! How necessary it is for all these drives to be allowed to unfold without restraint, to raise the sexual intoxication to full satisfaction!” If women fail to experience orgasm on a regular basis, this more than anything may be the fault of the partner. “The man has to be able to pet the clitoris with an experienced hand,” Schnabl recommends. “For this he has to be very tender and responsive to the woman’s reactions.”

Apart from female pleasure, he tackles unfazed in page after page previously taboo topics such the sexual education of children (they need to learn to “to take into account the dignity of others”), masturbation (“these actions are neither shameful, nor unhealthy”), erectile dysfunction and premature ejaculation (“most sexual dysfunctions are psychologically conditioned”), the importance of petting (“an ideal addition to coitus”), various modes of contraception such as condoms, IUDs, and birth control pills (“society… has no right to dictate a woman when she wants to get pregnant”).

Perhaps what’s most fascinating about Schnabl’s book is that it comes from the conservatism of the Soviet bloc, yet it’s written in the best progressive traditions of the 1960s, even if his view is often limited by heteronormativity and belief in monogamy. Yet, he’s not quick to judge behaviors that are outside “the norm.” “Few people understand that the norms they consider correct are nothing more than a product of their upbringing, of their life experience, their personal experience, as well as all the environmental factors they grew up with,” he notes. “Sexual traditions are subject to various cultural-historical shifts and what was normal yesterday could be considered perverse today, and normal again tomorrow.”

The last few chapters of Man and Woman Intimately deal with exactly that sort of touchy material: “deviations,” in the lingo of the book, outside socially accepted norms: fetishism, voyeurism, sadism and masochism, transvestism, transsexuality, and homosexuality, among others. Although Schnabl inevitably harbored some of the prejudices of the day when it came to less normative forms of sexuality, he still refused to judge and condemn them outright. Genetic determinants, he notes, have probably exercised greater influence on homosexual behavior than environmental factors, and thus attempts to “convert” people to heterosexuality are to be considered harmful and useless. Gay people are regular members of society, represented in all professions (“greatly talented in arts and aesthetics”), and thus “arguments that have been used as a basis for laws against homosexuals, are all, with no exception, refuted by science.” He is also quick to give advice to the parents of gay boys (lesbian girls were less of a focus for him): “When parents face the fact that their son is gay, they are shocked. But they have to consider that this is the moment he needs their understanding and trust,” Schnabl writes. He is nominally supportive, though once again in a rather roundabout and equivocal manner, of trans people. Attempts to reaffirm their original sex with psychotherapy or drugs, Schnabl notes, show no results and the patients see them “as acts of violence against their most intimate self.” In certain situations, he concedes, “sex change is humane and an act of social justice.” For a conservative place like communist Bulgaria (and the Soviet bloc in general) these were truly radical, seditious opinions.

In fact, going through the book diligently, one comes out with the feeling that for Schnabl the only true “deviant” behavior, regardless of the type of sexual practice, is the dehumanization of the other, the kind of solipsism that avoids love and care, turning the partner instead into a simple object for satisfaction. “From a moral standpoint we can… judge actions and their motives only in relation to the well-being of other people,” he writes. Rereading Schnabl’s book in Bulgaria, in 2025, I think about how much has been gained and how much lost since its first publication, fifty-six years ago. How much capitalism has liberated the libido and how much it has in fact enslaved it. How wonderful that the silence and shame surrounding sex were punctured, and how dire the commodification of desire has become, how normal the objectification of people. Have we learned “to take into account the dignity of others,” or do we treat them as disposable products now, one more person to flip through on the marketplace of dating.

Yet I can’t deny that I feel a tiny bit nostalgic for the world my parents grew up in: not the ideological bullshit or the supposedly socialist values (though I’ve come to sincerely believe in socialist values), not the hypocrisy and moral conservatism, but the more intimate links between people, the less mediated interactions, and—dare I say—the more sacred place of sex in everyday life.