Within the Catholic Church, many bodies make up the body of Christ, and those have always included a variety of gender expression. A closer look at the lives of the saints reveal a counternarrative that substantively challenges a gender-normative narrative.

An introduction from the translator, Karim Kazemi

On April 21st, Pope Francis died of a stroke. In the Catholic Church’s two-millennia-long ledger, Francis’s papacy registers as an unprecedented cascade of firsts: the first Latin American, the first Jesuit, and the only pontiff ever to declare, without any caveat, that God loves queer children as they are.

Francis’s ministry charted fresh territory. His maiden foray beyond Rome sidestepped the standard circuit of basilicas and royal receptions. Instead, he headed straight for Lampedusa—the isle off Italy’s coast where battered rubber dinghies, crammed with migrant families, often founder. Leaning over the rail of a Coast Guard cutter, he lowered a wreath into the Mediterranean’s cobalt waters, a solemn liturgical gesture to honor the drowned.

Throughout the twelve years of his tenure, Francis sounded the alarm on climate collapse and rising nationalist retrenchment; convened young social scientists in Assisi to envisage post-neoliberal economic horizons; mobilized the Church’s global network of missions to defend indigenous communities from cultural erasure and industrial plunder; ushered women and laypeople into the Vatican’s administrative upper echelons; and even insisted, in his January 2024 peace message, that the swift-rising tide of artificial intelligence deserves our deepest moral reckoning. Francis also crucially expressed his solidarity with the Palestinian people, phoning the priest of Gaza’s sole Catholic parish daily since October 2023, and calling for a ceasefire, on Easter Sunday, in his final address—a common-sense stance that is nevertheless scarce among political and religious leaders in the West.

Francis garnered broad, overwhelming favorability worldwide—proof that his reforms echoed the convictions of the many, not a vocal left-wing fringe. Francis successfully steered the oldest corporation away from the brink of irrelevance in an increasingly secular age, yanking its helm hard to port—toward the margins, toward the dispossessed, toward the poor.

Last year’s Conclave—starring Ralph Fiennes, Stanley Tucci, and John Lithgow as rival electors, and Isabella Rossellini as an implacably taciturn administrator-nun—dramatizes the deliberation that is now underway to elect Francis’s successor, lending Michaelangelo’s painted vault a lustrous Hollywood sheen. Contenders emerge and are eliminated, knocked out, as their long-buried indiscretions and extremist leanings are brought to light. Over catered luncheons, and after hours, behind closed doors—through soft-spoken promises, precision-targeted flattery, and velvet-glove extortion—the fathers wage their campaigns. (With Oscar buzz at its back, I was struck by how, perhaps inadvertently, the conflict’s staging seemed to reproduce the calculated charm offensives that movie studios mount, during awards season, to nudge their vehicles toward victory.)

The film trades on the real-life ritual’s secrecy and intrigue but stretches credulity when it asks us to believe that the content of the clerics’ disagreements are scraped, solely, from ongoing U.S. culture wars—women’s rights, anxieties about multiculturalism, the cry of “no going back”—and eschewing even a glimpse of other forms of probable fodder, such as the rehashing of arcane, centuries-old sectarian beefs. Ultimately—spoiler alert—a wildcard cardinal from Kabul comes out ahead, and only after his investiture is announced and therefore irreversible does he disclose that he was born with an intersex trait.

The film’s surprise final act strikes at gender anxieties that have haunted the Catholic Church for millennia. These fixations crystallized most persistently in two myths: that of the sixteenth-century female Pope Joan, allegedly unmasked only when she unexpectedly gave birth mid-procession; as well as that of the sedia stercoraria, a perforated chair purportedly used to manually verify cardinals’ genitals. In the following article—originally published in a February 2023 issue of Relatos e Historias en México—Antonio Rubial García, professor emeritus of history at Mexico’s National Autonomous University, traces the long lineage of tales of saints who crossed and complicated gender boundaries in medieval Christian myth.

Saint Margaret was a beautiful, wealthy, and noble woman, blessed with every grace, who lived with a most decorous restraint, with maidenly modesty and trembling virtue—qualities that attracted the attention of a young nobleman who asked for her hand in marriage, to which Margaret's parents gave their blessing. Upon the day of her betrothal, noble families from across the region gathered in the town; however, the young woman was deeply conflicted. She wondered why she should celebrate such a lamentable act as the loss of her virginity. Instead of putting on her wedding dress, Margaret cut her hair, disguised herself as a man, and fled from her father's house. After walking for several days, she arrived at a monastery, said her name was Pelagius, and petitioned to take the habit.

Brother Pelagius proved such an exemplary monk that a convent was entrusted to his care, and he tended to its material and spiritual affairs with equal grace. But the Devil, seeing the convent prosper, moved a pregnant nun to name Brother Pelagius as her seducer. The accusation found its mark: the monk was cast out, condemned to live as a hermit in a nearby cave.

Dying, Margaret/Pelagius wrote to the monastery’s abbot, disclosing his origins, the fact of his sex, and requesting that the sisters prepare his body for burial. Jacobus de Voragine, a thirteenth-century archbishop of Genoa and compiler of The Golden Legend, a widely-circulated compendium of the lives of the saints, concludes his account of Saint Margaret’s life: "The monks and nuns did penance for the offense they had dealt such a virtuous soul, whose mortal remains they buried, with utmost reverence, in the sisters' cemetery." The tale, devoid of dates or locations, is clearly a moral fable with no historical basis.

Variations of the Same Story

A similar narrative, with some variations, appears in Voragine’s Golden Legend: Saint Marina, who, passing herself off as a novice , entered a monastery after her father compelled her to make her first profession there. When he died, "Brother Marino" kept her secret, following her father's advice. Like Brother Pelagio, she was falsely accused of rape by a pregnant young woman and was expelled from the community, although she lived in poverty nearby, begging for alms.

The abbot and the monks, seeing her submission, considered the punishment sufficient and allowed her to reintegrate into the community, but only by performing the most menial tasks. After Brother Marino passed away, the monks prepared her body for burial and discovered she was a woman. Remorseful, they had a tomb made for her in the abbey. At the time of her death, the woman who had falsely accused her was possessed by a demon and wandered the roads and villages, crying out her sin of slander. She was freed from the demonic possession when she approached Saint Marina's tomb and asked for forgiveness.

Similar stories were told about Saint Eugenia of Alexandria who, dressed as a man, took vows in a monastery and rose to become its abbot, but when maliciously accused of having impregnated a young woman, she was stripped free, with sudden violence, of her vestments and her anatomy was publicly exposed; and, as if that weren’t enough, being Christian, she suffered martyrdom. Another instance appears in the narrative of Saint Liberata, who, having petitioned God for a beard to make herself unmarriageable, was crucified by her father.

Saint Euphrosyne of Alexandria, born in the fifth century to a family of conspicuous fortune, presented a remarkably similar life trajectory, though scandal never touched her name. Reprising, once again, that deliberate emphasis on the child’s extraordinary feminine beauty, this legend recounts how her father, Paphnutius, arranged her union with a man of comparable standing. To dissolve the bonds of a fate she never selected, Euphrosyne clothed herself as a man. To remain beyond her father's recognition, she secured admission to a male monastic order under the name Smaragdus—”emerald” in Latin—disguising herself as a court eunuch fleeing the perfumed intrigues of imperial circles, and seeking a life of greater ascetic rigor.

Her beauty proved irrepressible. It outmaneuvered her habit, betraying its presence, like light stealing beneath a door; it awakened impure urges in her brothers. The abbot, observing this disturbance, confined her indefinitely to her cell.

The stories of female saints who had passed as men achieved remarkable circulation throughout the churches of the Byzantine East. Carried along by commerce and conquest, these narratives arrived in the Christian West, where—once rendered into Latin from Greek—they were received by Jacobus de Voragine and other hagiographers with particular interest. A measure of their reach: in Spain and the Americas, Saint Euphrosyne is frequently depicted donning, inexplicably, the Carmelite habit. (That order claimed her as one of its most illustrious members, despite the historical impossibility—it wasn't established until centuries after Euphrosyne/Smaragdus had died.)

Other, similar narratives stayed locked within Eastern tradition, like that of the hermit Saint Onuphrius, who often appears in Orthodox iconography, depicted with breasts—somehow discernible through the flowing beard that, obscuring his pelvis, reaches his knees. In these Greek accounts, the narrative presents a saint born female whose ceaseless entreaties to God for bodily transformation received divine reply: Onuphrius was made male, and he withdrew into the scorching solitude of the Thebaid desert.

“The woman of Male Bearing”

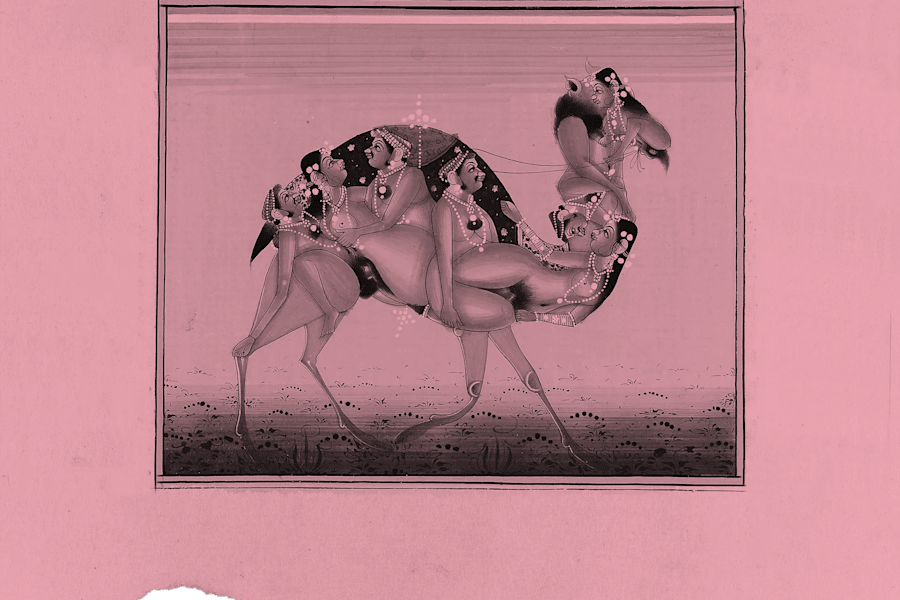

The success of these narratives, residual fragments of ancient myths like that of Hermaphroditus, stemmed from an intense preoccupation with female masculinity between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries.

As these stories circulated, certain women put them into practice. Such was the case with Saint Joan of Arc, the Maid of Orleans, who, in soldier's garb, led the French armies that expelled the English at the end of the Hundred Years' War.

Her accomplishments notwithstanding, accusations of witchcraft led to her execution at the stake by an inquisitorial tribunal. The Catholic Church rehabilitated her reputation decades later, culminating in her beatification in 1909 and canonization in 1920. The ninth-century legend of Pope Joan pushed this narrative pattern toward more lurid extremes. The dissemination of this myth appears to have originated in the Byzantine Church during the schism of Patriarch Photius, when Pope John VIII's adversaries accused him of being excessively pliant and “ladylike” in his manner of managing tensions between Rome and Constantinople.

These caustic misogynistic charges were later wielded by Protestant reformers, who regarded a woman's occupation of the papal throne as evidence of the Catholic Church's degeneracy. Like Catholics, Protestants rejected women's participation in ministerial roles.

This period also saw the dissemination of another myth: the sedia stercoraria, originally referring to a seat with a central aperture in its base, which purportedly allowed for verification of the future pontiff’s “masculine attributes.” Popular imagination, fueled by Pope Joan's legend, recast this liturgical chair as a device meant to ensure no woman could occupy Saint Peter’s throne again.

Transvestism, Religion, and Society

Whereas female transvestism was understood as a logical aspiration toward “superior” status, men who clothed themselves as women were seen to sully the inviolable nature of manhood. Gender transgression gained sanction only during festive intervals—most notably the prescribed chaos of carnival—where it functioned as a deliberate symbol of suspended order. Regarding this expurgatory threshold as preparation for the discipline of the Lenten season that lay ahead, the Church reluctantly endured such inversions.

The Catholic Church continues to deny the priesthood to those whose bodies are, at birth, deemed female, barring them from the supreme vocation available to Catholics: the power to transubstantiate bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ.

The stories of Saints Margaret/Pelagius, Marina/Marino, Eugenia, Euphrosyne/Smaragdus, Onuphrius, Liberata, and Joan of Arc all invite reflection on contemporary discussions surrounding gender and transgender identity, the social roles assigned to both sexes, the ongoing struggle for equity in professional opportunities and recognition between the sexes, and respect for diversity.

Ultimately, these narratives offer a historical perspective on a principle now confirmed by modern psychology and gender studies: within the human psyche, masculine and feminine traits coexist, independent of our sexual inclinations or physical form. That these narratives flourished within religious communities—spaces defined by strict gender segregation and hierarchy—reveals how even the most rigidly structured societies generate counternarratives that challenge foundational assumptions about gender and embodiment.