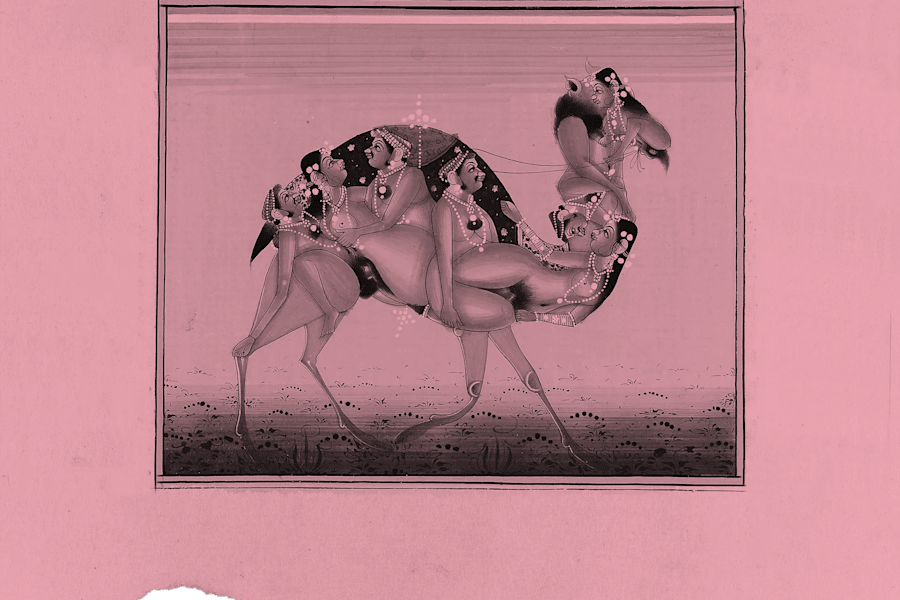

Joanna Piotrowska, "Untitled," 2024, Collage, 60 x 50cm

An image portfolio curated by Lou Stoppard.

My sister worked as a groom for racehorses, massaging their oily coats with a rubber paddle that attached to her palm with a strap. I waitressed. The rule in my parents’ house was that, at fourteen, you found a job.

No one seemed to mind that I was underage. I pulled pints, ate left-overs directly from customers’ plates in the kitchen when I was meant to be stacking the dishwasher. Whenever the chef needed me, he rang a small silver bell. Twenty years have passed since then, but when I eat out, I still listen for those summoning chimes, aware of the bristling anticipation among staff, the sways between routine and crisis, the manoeuvrings that are meant to be out of frame.

I loved the job, kept on with it for more than five years. I loved talking to people at the bar, loved the licence to ask almost anything: what do you do for a living? What did you dream of being, when you were young? Is marriage worth it? I would not have become a writer if I hadn’t been a waitress. It taught me to notice, to listen, to perform, to emote in the exact key required to get the most from each source.

Eleonora Agostini, "Untitled," 2023, from A Study on Waitressing

Eleonora Agostini, "Untitled," 2022, from A Study on Waitressing

The photographer Eleonora Agostini’s series, A Study on Waitressing, was motivated by growing up watching her mother wait tables at her family’s restaurant. She felt a mix of admiration and disturbance when observing her mother switch tone, or arrange a new expression or posture, to placate the whims of each client. In the Agostini eatery there were curtains that separated the diners from the kitchen, “backstage curtains,” as Agostini calls them. Her words make explicit the theatrical nature of the restaurant space and the characters within it, each playing parts that draw not only on the context—the architecture and props that divide guests and server—but on wider power balances that bolster the set-up: dynamics relating to class, gender, age, status, money.

The performance of identity that we all partake in daily is made uniquely visible in a restaurant. That’s one of the reasons I loved being there: the curious sensation that something fundamental was simultaneously being revealed, and, in turn, through the starkness of that revelation, disturbed. Watching a grown man pay to feel power, as he asked me to recite the specials again, magnanimous as he left an above-average tip, didn’t make me feel cowed by wider patriarchal forces and structures, so much as buoyed by their seeming fragility, the desperation with which some clients needed to make them explicit. Their power became cartoonish, camp.

I knew that most people viewed me, the waitress, as subservient—there to be compliant and decorative and useful, closer to furniture than the customers I served. But I knew I was the one who could make it all fall. I was the conductor: deciding who sat where, who got focus and when. If I had ever dropped the act and broken character, I would not only have upset someone’s evening, but punctured their ego, their faith in the hardiness of the status quo. You could say that’s a limited kind of power, but the power to reveal, to expose, is rousing and addictive, and explains my later interest in writing, and in images.

Photography is similar to waitressing—one is at the mercy of chance when it comes to who enters your space, but one is ultimately choreographer and conductor. One chooses where to place attention—who gets memorialised, who is special. One assumes a form of invisibility: a subtle voyeurism that is integral to the job.

The power dynamics between imagemaker and subject are dense and messy and often problematic. The images that I have selected here show an interest in and awareness of these gray areas, in the ebbs and flows of power. In their own way, they all relate to the theme of control. Control of one’s body, control of one’s mind and desire, control of one’s image: control of image, and narrative, in general.

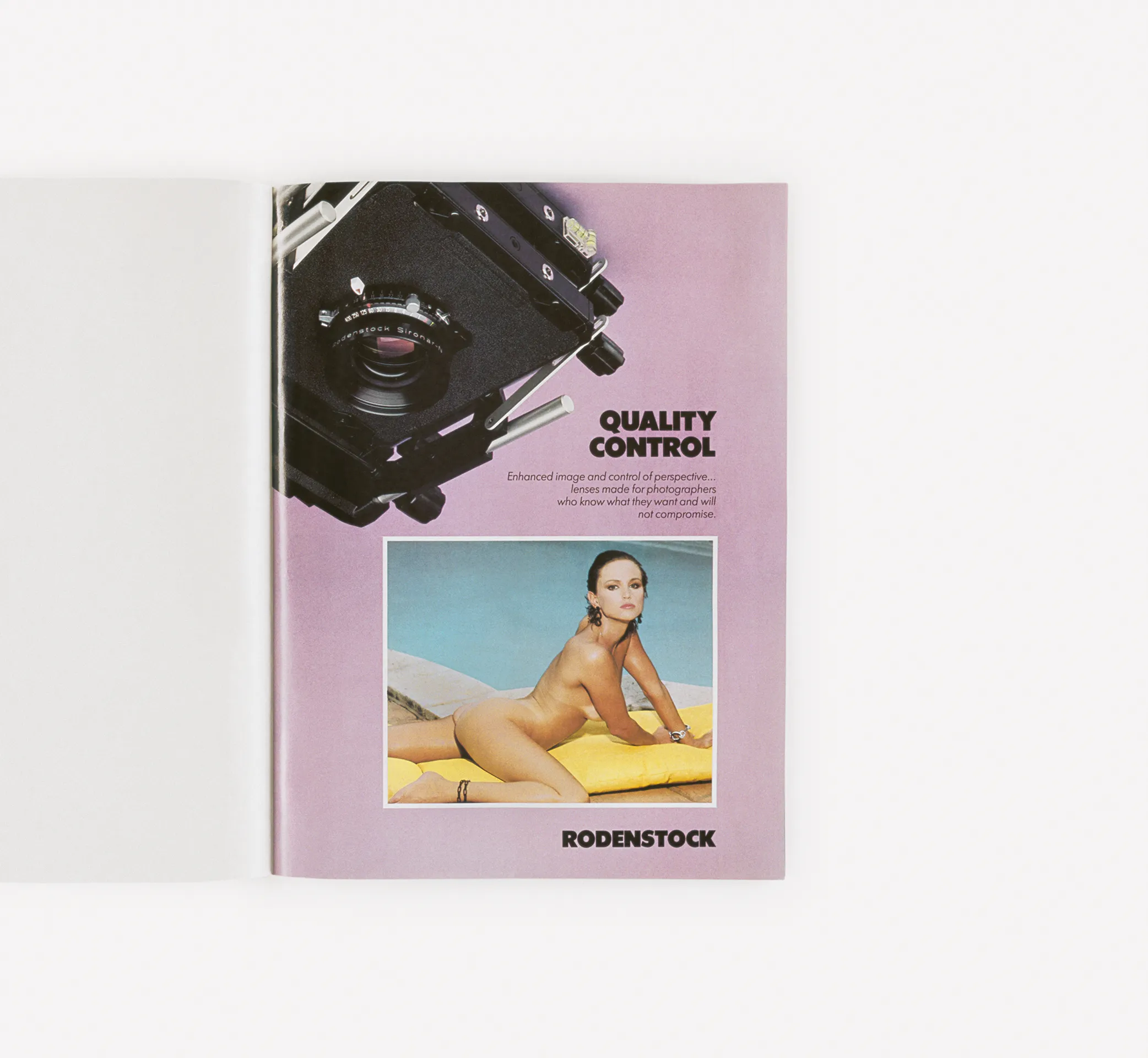

Anne Collier, Quality Control, 2016

Anne Collier’s practice focuses on appropriating images of women from adverts, magazines, and album covers from the 1970s and ’80s. In her work, we are confronted with the power of the camera, and of images, to exert control, and to seduce. To define what is normal, and, in turn, to create a desire to be part of that normality, through buying, acquiring, and being. The technology itself has become a part of that commercial cycle: cameras are coveted items in themselves. They are a must-have, or rite of passage, offering control both of our own image, and the images of our possessions and loved ones—things marketed to men as largely the same thing.

Justine Kurland, “Outlander”, from the series SCUMB Manifesto, 2022

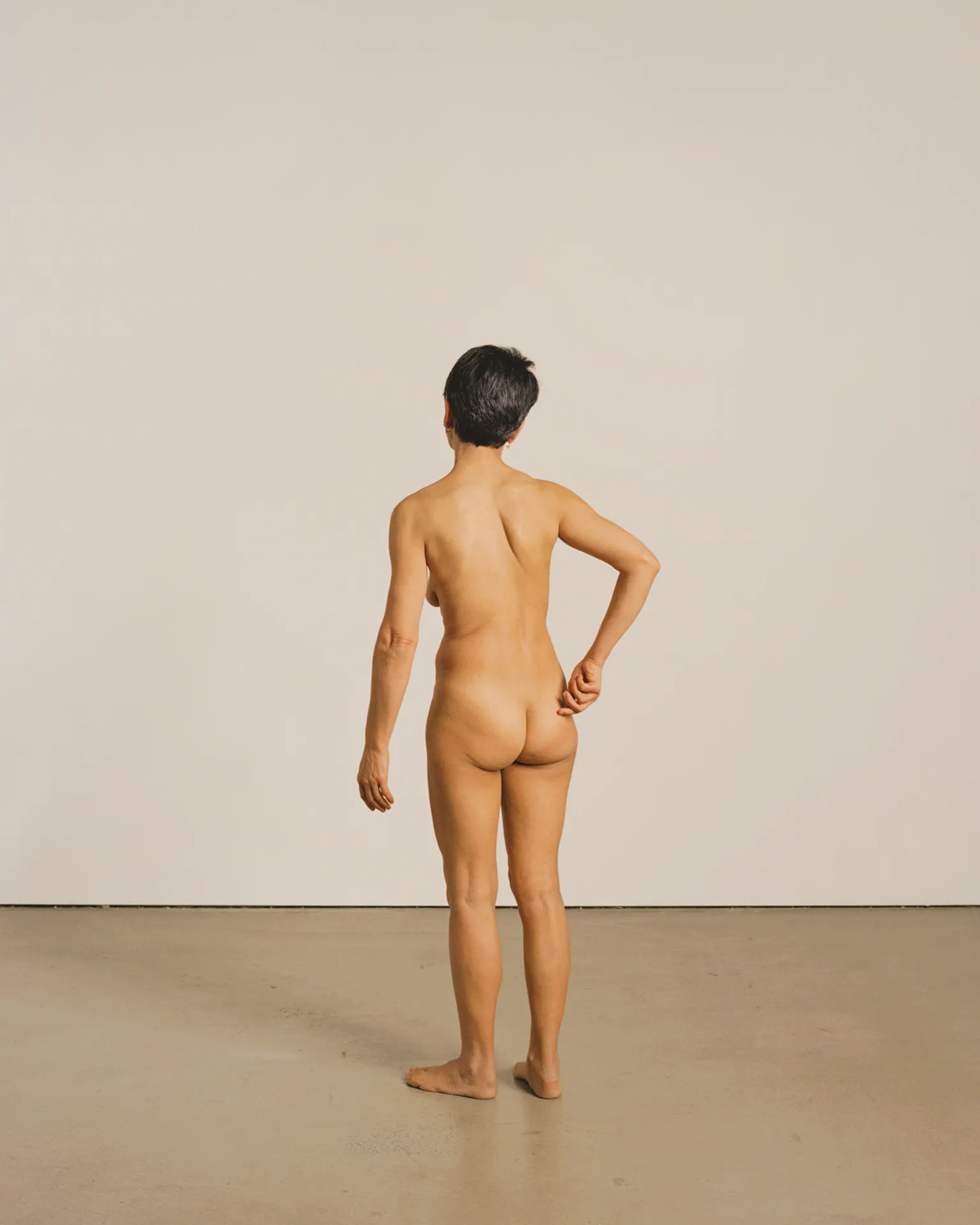

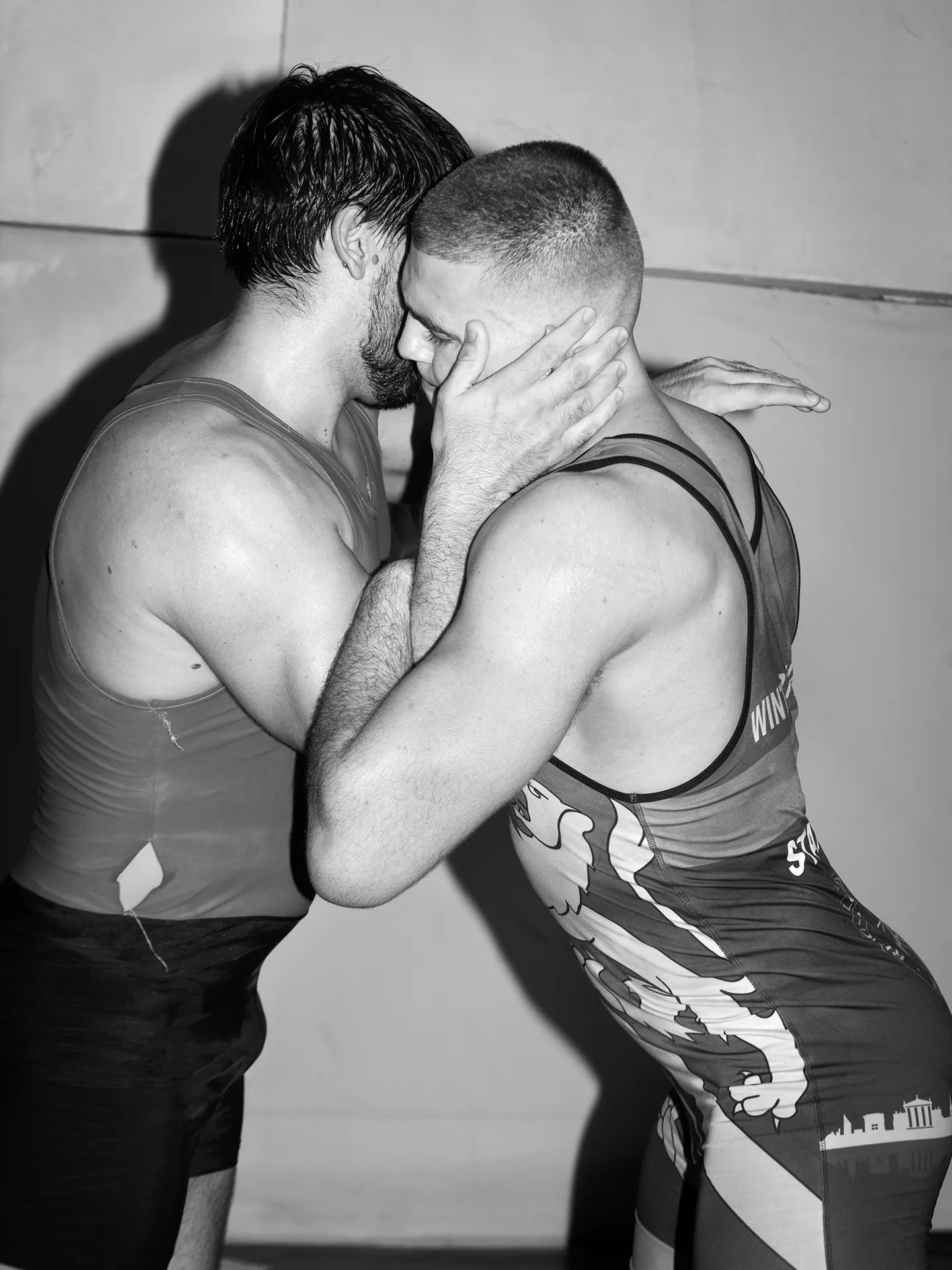

Olivia Arthur, Roman wrestlers, 2021, from the series ‘Murmurings of the Skin’

Back in 2019, the artist Justine Kurland began chopping up books by canonized male photographers. Like Collier, she decided to appropriate: reauthoring the severed images by reshaping them into collages. The image here, Outlander, was made from, and titled after, a box set of images by William Eggleston: “a man who had bragged his compositions are based on the confederate flag, published by Steidl on the nicest paper and the best inks money can buy,” as Kurland put it to me. Her project shifts control and agency: both Eggleston’s and that of the subjects within the pictures. It would be simplistic to say that Kurland simply subverts control: she does not return autonomy to his subjects, or even particularly seize it herself. Instead, she throws it all up in the air—seeing, in the radical acts of destruction, fixing, care, a chance for conventional power to be scattered. The works, she tells me, are investigations of “circularity, revolution, and the formal and symbolic properties of the vagina.”

I discovered the work of Olivia Arthur around the same time I gave birth, two years ago. To be pregnant is to feel both startlingly powerless and uniquely powerful. I oscillated between feeling in service to my daughter—like a machine, required only to provide for her, to keep her alive—and God-like: able to create life; to be, to borrow Kurland’s word, revolutionary. This was a sensation Arthur also felt and it sparked this series, Murmurings of the Skin, which depicts the human struggle for power over one’s own body, the quest for dignity, optimization, and stability. This image, of wrestlers, plays with the contradictions inherent to our experience of the body: tender, violent, erotic, platonic.

When my daughter was born, I found myself thinking a lot about my waitressing years—I was always “listening for the bell,” attuned to a shift in her expression, any sound, any cry, any movement, ready to rush over, to help. I mimicked past gestures—stacking things on my wrists, using my back to push through doors while my hands were full, carrying her tiny body, using each individual finger to pick up a toy or muslin, my hand recreating the claw required to hook five empty glasses, one on each finger.

Joanna Piotrowska, "Untitled," Collage, 60 x 50cm, 2024

Joanna Piotrowska’s image restages an existing work, of a mother and a child, in which the former stretches a hand towards the latter on the floor. In this work, profiles have shifted: the two subjects are sisters, adults of almost the same age. The gesture, the subtleties of a body position—seemingly so tender, so encouraging, when it is the hand of a mother—suddenly look warped. They could be aggressive, demeaning, even vaguely sexual, in this new incarnation. The question of control—of mother over child, of child over mother, of adult over adult, Piotrowska over sitter, photographer over subject—all lap around the image. In the background, Piotrowska returns to a domestic motif that fascinates her, and appears consistently across her works—a slightly open door which reveals another door.

Lewis Ronald, "Sole, Milan, 23 February 2020," 2020

While Piotrowska’s open doors suggest an expanse—ancestors upon ancestors, histories upon histories, memories upon memories—Lewis Ronald’s image portrays a shuttering, where that flow of action abruptly stops. It was taken in Milan in early 2020, the very same day the government began closing public institutions in response to the coronavirus outbreak. We see a slick black shoe—part of the traditional uniform of formality and power—with a tear in the sole. The position of the foot recalls prayer: a country’s history of Catholicism, of domination and shame. When he made the portrait, Ronald was waiting outside a suddenly shuttered museum. “I started asking passers-by to show me the soles of their shoes. Like everyone else, I was locked out of the gates,” Wiser told me. “It felt like a quiet gesture of intimacy in a world that was beginning to close in.” Everyone on that street now had freedoms even more limited than when they woke up that morning. They were awaiting instruction on where and how they could move, how they could interact, what to do next.

David Campany, "Self Portrait Falling," 1994

David Campany, "Self Portrait Falling," 1994

David Campany’s photograph depicts a space filled with images, Piccadilly Circus: a space where the seductive powers of photographs—to illicit desire, insecurity, shock—is made blatant by brands and advertisements. Campany set up a camera and had a friend take the images. The first in the series were carefully scripted: Campany at the side of the road, Campany in the road clutching his stomach, Campany collapsed in the road. The photographer then had the remaining 9 shots on a 12-shot roll of film to capture whatever happened next. An “experiment with control and its limits,” as Campany put it to me. “In the end, I was rescued by a bunch of German tourists and carried to the other side of the road.” The image we see here—Campany down, concern bubbling around him—at first glance seems an immediate study of lost control: the shame and confusion and mess of a body that has failed. But the choreography that surrounds the project—both in terms of the studied intention behind the earlier images, and the deliberate desire to cede responsibility when it came to the others—gives the image its lingering oddness. Various people in frame, like the caring tourists, will have walked away from the interaction feeling they were the one in control. The ones looking after a vulnerable stranger. They will have had no idea of the wider orchestrations, of their role as sub-characters in a bigger plan. Photographers seek control: hoping to hold the world still for a while. But they know it will swiftly be gone: handed over as the image/object is passed on and opened to interpretation and criticism. The reality of one’s control is always tenuous. We can lose it without even realizing it. If we ever had it at all.