ISO: the words behind the acronyms and the people behind the personals

ISO: the words behind the acronyms and the people behind the personals

MORE, MORE

More fun than Dudley Moore movies; More intelligent than amoeba; Easier to talk to than God; Added together—what is the sum? A 22-year-old whose life reads like a Russian novel? Yes and more! Is there Power and Trust in DC? Are you intense or just fooling yourself?

So goes a personal ad from the Spring 1986 issue of On Our Backs, a lesbian erotica magazine whose classifieds sections were more art form than advertisement. These words—carefully strung together like a poem by an anonymous writer in Washington, DC—spell out the naked desire of a queer community in flux. It was just before the dawn of the internet, and the 1980s, a decade of excess and extravagance, was in full swing. The theme of the moment? Sex.

Buried in the classifieds section in the back of a newspaper or magazine, personal ads were where readers flocked to see who was asking for what. If you were a lonely queer in the 1970s looking for love—or friendship, or sex, or something else entirely—the personals were a place for you. From booty calls to marriage proposals, the personals paved the way for love to transcend the boundaries of convention and, eventually, enter another dimension: the internet. Much like dating app profiles today, personal ads followed a formula, listing details like menu items: age, gender, hobbies, features, etcetera. Abbreviations like “NSA” (no strings attached), “GBM” (gay Black male), “D” (divorced), and “ALA” (all letters answered) made up a coded language of letters. It wasn’t necessarily secret—anyone familiar with classifieds would be able to decipher the acronyms—but it was discrete, and concise.

The personals feel like a relic of the past now, but in the decades before the internet, they represented something of a lifeline. Discretion was incredibly important to the earliest queer journals and newsletters in the United States, which published and distributed issues in the 1940s, ‘50s, and ‘60s, despite homophobic censorship laws. The USPS, for example, refused to mail ONE Magazine in 1954, calling it obscene; ONE successfully challenged this categorization at the Supreme Court in 1958. Subscribers lived in constant fear of being caught in possession of homosexual materials; magazine staffers were routinely surveilled by the FBI. Publishing queer journalism was dangerous work. But by the 1970s, the gay liberation movement was well underway and queer periodicals were popping up all over the country.

This was an era when queer literature was everywhere. There was Ain’t I A Woman, in Iowa City; Killer Dyke, in Chicago; Lesbian Tide, in Los Angeles; Gossip Boy, in Oklahoma City; Fag Rag, in Boston; Gaysweek, in New York City; Homocore, in San Francisco; DRUM, in Philadelphia; the list goes on. Contributors wrote about everything from local news and lifestyle trends to national politics and parenting. In these papers, especially the local ones, the personals flourished—because, much like dating apps today, proximity was everything. For the first time, queer people could freely advertise their desire. And they really went for it, no holds barred. Character limits meant lots of acronyms, little ambiguity, and sexually explicit requests—etiquette be damned.

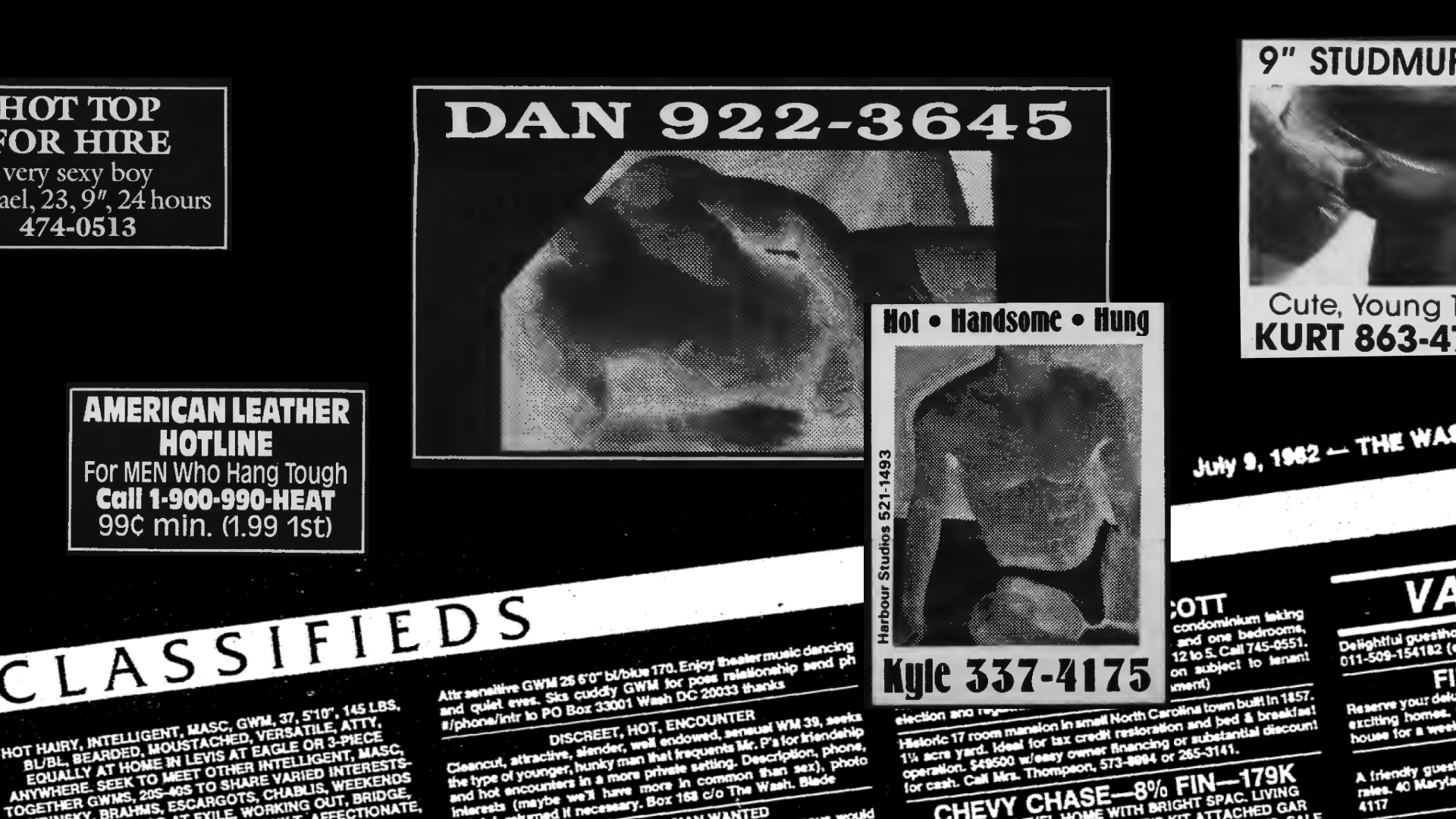

Writers advertised their desire with admirable audacity. In a January 3, 1986 issue of Dallas Voice, someone called Mike says “Wanted! A masculine, hairy, uncut man to have sex with. Call Mike.” In a July 9, 1982 issue of The Washington Blade, unapologetic declarations run the gamut of asks: “RELATIONSHIP WANTED”; “FED UP W/ BARS & TIRED OF PICK-UPS!”; “CAT PEOPLE”; HEY DUDE, WANNA WRESTLE? OR A HOT FANTASY?”; “DISCREET, HOT ENCOUNTER”; “MONOGAMOUS MAN WANTED.” In the Bay Area Reporter’s issue from March 28, 1991, personals for “Ass Licks” and “Porno” are interspersed with (slightly) more discreet sexual innuendos like “WATER SPORTS” and ads for services like the “American Leather Hotline” and “SEXY! STEAMY! HOT! 1-800-926-MENN.”

This diversity of desire conjures two truths: queer people are not a monolith, and a penchant for liberation means that love and sex inevitably get liberated, too. Across the country—in both urban coastal settings and midwestern gay oases—these papers held a world of newly articulated desire between their pages. They were public representations of communities that, just a few decades prior, were all but invisible. Here, sex talk wasn’t just foreplay; it was a revolutionary act.

For lesbians, perhaps the most famous home of all this steamy rhetoric was the aforementioned On Our Backs, the San Francisco-based erotica magazine that ran from 1984-2006. On Our Backs was controversial, to say the least: at a time when feminist communities were debating the politics of porn and fighting the so-called “sex wars," On Our Backs was decidedly pro-sex. Even the snarky title—penned in reference to the (anti-porn) feminist magazine off our backs—positioned On Our Backs, from the get-go, as a trouble-maker. Its contents, which featured pages and pages of nudes, posed a critical challenge to activists at the time: could a publication that featured naked women between its pages really be feminist?

It’s difficult to find digitized issues of On Our Backs today due to copyright laws and issues around consent. But tucked away in four tidy cardboard boxes in an upstairs room of the Lesbian Herstory Archives, you’ll find almost every issue, perfectly intact. The personals are the final section of the classifieds, all the way in the back of each magazine. There, even the titles of each entry are erotic in their own right: “PULL MY HAIR!!”; “HORNY AND HOT”; “SEX-STARVED BOOKWORM”; “BABY BUTCH.” Leafing through these pages on a balmy June afternoon, I am struck by the flimsy, precarious reality of the material itself. For while the internet feels like it might go on forever, printed magazines are painfully finite. The paper is delicate, well-worn from the many queers who have held onto these pages in search of love. I hold it cautiously now, not wanting to disturb all that desire still contained within. But in the end, I can’t help but break the spell. I pull out my iPhone from my back pocket and take a photo, yanking the pages into the present with a single click. It’s an act of defiant preservation: in a world that continues to justify queer erasure, history tells us that queers persist.

- Emma is a freelance journalist and amateur archivist, mostly writing about queer culture and DIY. She lives in Brooklyn.

Sources

- Dallas Voice: Ritz, Don. Dallas Voice (Dallas, Tex.), Vol. 2, No. 35, Ed. 1 Friday, January 3, 1986, newspaper, January 3, 1986; Dallas, Texas. (https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth615748/: accessed June 8, 2023), University of North Texas Libraries Special Collections.

- Bay Area Reporter: Bay Area Reporter (San Francisco, California), Vol. 21, No. 13 Thursday, March 28, 1991, newspaper, March 13, 1991; San Francisco, California. (https://archive.org/details/BAR_19910328/page/n51/mode/2up) GLBT Historical Society.

- The Washington Blade: The Washington Blade (Washington, DC), Vol. 13, No. 14 Friday, July 9, 1982, newspaper, July 9, 1982; Washington, DC. (http://hdl.handle.net/1961/dcplislandora:10504) DC Public Library, The People's Archive, Periodicals.

- The Gay Peoples Union (GPU): The Gay Peoples Union (Madison, Wisconsin), Vol. 7, No. 2 November 1977, newspaper, November 1977, Madison Wisconsin. (https://digital.library.wisc.edu/1711.dl/HJ4HVULU3DSD483) The University of Wisconsin-Madison Libraries, Archives Division, Gay Peoples Union Collection.