Your anger is a catalyst. Unleash it.

You might be feeling angry right now, and, if so, you are not alone. This anger is often deemed unpalatable by society: after all, an angry woman is the shrewish wife, the crazy ex-girlfriend, the hysteric. Throughout history, feminine rage has been a natural, and propulsive, reaction to structures and systems designed to keep femmes at a disadvantage. This rage is more important than ever, with a changing world threatening the autonomy of so many.

Across the world, 736 million women over the age of fifteen—almost one in three—have been subject to physical or sexual violence. In 2023, on average, 140 women or girls were killed every day by someone known to them. The risk of violence is even greater for marginalized communities; 50% of the 36 transgender and gender-expansive individuals killed in the US in 2024 were Black, at a time where the US government is carrying out an unprecedented attack on transgender communities.

There’s much to be angry about. Rage is destabilizing. Rage is radical. Yet when femmes express anger, they have risked historically—and still risk—their views being reduced and delegitimized. But in rage we are stronger.

Female rage throughout time

In the Victorian era, it was a commonly-held belief that women were more emotional than men, otherwise known as “hysterical”—a state of being and emotion for which there developed a whole industry of cures, including the invention of the vibrator. The term hysteria itself comes from the Greek hyster, or womb, with the blame for women’s emotions reduced to the uterus. Absurdities like this risk glossing over the cruelty and degradation of the “cures,” and the very real delegitimization of women’s position in society. In 1859, a quarter of women were said to be suffering from hysteria. Expressing rage wasn’t just unsightly; at its worst it could get you incarcerated and lobotomized.

“Hysteria” has no longer been understood as a medical disorder since the 1980s, and yet female emotion expression continues to be used against femmes, whereas men displaying the same degree of emotion are validated and even celebrated—just think of the outburst and demonstrations of Brett Kavanaugh during his 2018 hearing to defend himself against allegations of assault, or indeed cast your mind to behavior defining any day in the current presidential tenure.

But rage can be a driving force. When negotiations failed to see progress for the suffragette movement of the UK in the early 1900s, they began to employ violence, with bombing and arson campaigns, members chaining themselves to fences, and hunger strikes. Second-wave feminism in the 1960s brought with it publications such as the 1968 SCUM Manifesto, a vitriolic document of female rage. Anger moved into the suburbs and the mainstream. Even when dismissed as “bra-burning” it resulted in the outlawing of the gender pay gap, in access to birth control regardless of marital status, and—temporarily—access to abortion with the 1973 establishment of Roe v. Wade (more on that later).

Representations of female rage

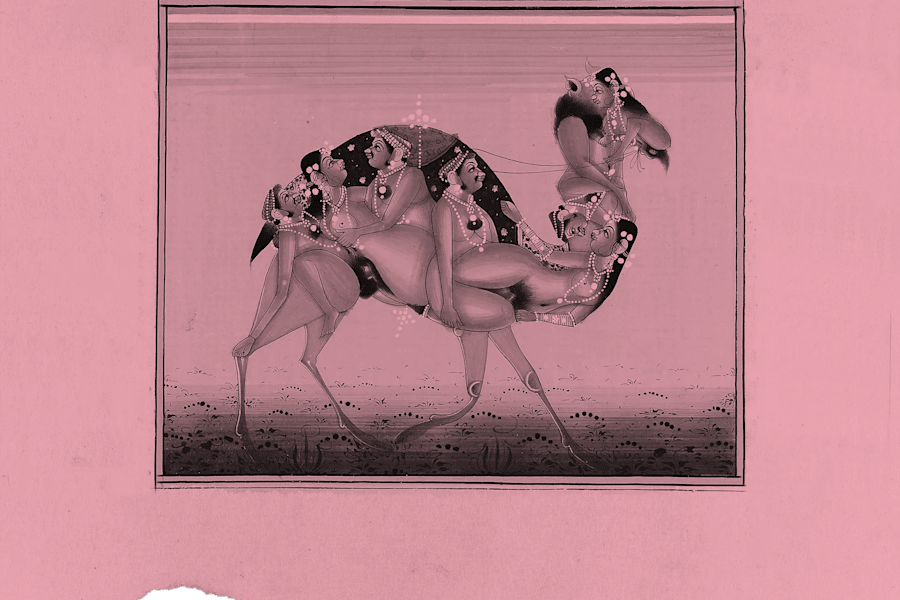

Feminine rage has long been portrayed as something monstrous in art across cultures. Euripides’ Medea in Greek mythology saw her rage drive her to the unspeakable act of infanticide, a rage inspired by the betrayal of her husband, making her an enduring symbol of its ugly potential. Medusa, punished for being raped, becomes another monster, her beauty unrecognisable.

And yet Medusa has the power to turn others into stone. There is power and catharsis in Artemisia Gentileschi’s 1620 painting, Judith Beheading Holofernes, one of the most famous depictions of female rage. Inspired by an earlier version, painted by Caravaggio some twenty years before, Gentileschi’s portrays Holofernes with the face of her rapist, Agostino Tassi: he would go on to be convicted, after Gentileschi underwent an arduous trial. Elisabetta Sirani is another painter who didn’t shy away from depicting rage following sexual violence, with her 1659 Timoclea Killing her Rapist, in which Timoclea actively pushes her attacker down a well.

Today, we most often see female rage showcased in film. Here it can veer between the sexualised (Jennifer’s Body, where Megan Fox is demonically possessed and becomes a man-eating succubus), the abject (Carrie, where abuse and bullying precipitates a supernatural and terrible revenge), and the sociopathic (Fatal Attraction, where a rejected woman gives rise to the “bunny-boiler” trope). But while a character may be given a certain power and legitimacy by their rage—at least temporarily—it’s not a path to redemption, with all three examples ending up dead. Rage is still there to be curtailed.

Femme rage and race

Black women suffer disproportionately more violence than the average person, with 45.1% of Black women experiencing violence from an intimate partner in the U.S. Yet tropes such as the “angry black woman” persist, where Black women expressing anger are dismissed for their emotionality, or are even seen as a threat—including by white women. As Sarah Ahmed puts it: “The figure of the angry black woman is a fantasy figure that produces its own effects. Reasonable, thoughtful arguments are dismissed as anger (which of course empties anger of its own reason), which makes you angry, such that your response becomes read as the confirmation of evidence that you are not only angry but also unreasonable!” Later in the essay she continues, “To speak out of anger as a woman of color is then to confirm your position as the cause of tension; your anger is what threatens the social bond.” Feminine rage is an intersectional project, but the anger of women of colour is, too often, reduced even further.

In Audre Lorde’s vital 1981 essay, “The Uses of Anger: Women responding to racism,” she describes white feminism’s often-uncomfortable relationship to race, to the anger of Black women, and its interpretation as reprimand or accusation against white women. She states "When women of Color speak out of the anger that laces so many of our contacts with white women, we are often told that we are 'creating a mood of helplessness,' 'preventing white women from getting past guilt,' or 'standing in the way of trusting communication and action.’” White female rage can be complicit in minimizing or sidelining the experiences of femmes of color in ways not dissimilar to patriarchal structures.

Bodily autonomy

It seems disheartening to mention Roe v. Wade earlier in this piece, knowing that not 50 years later such a landmark ruling—one which changed the lives of so many—would be overturned. Access to abortion and to birth control is gravely under attack in the U.S. At the same time, attacks on the rights of trans people are intensifying, with passport applications for trans and non-binary citizens suspended, and urgent threats to funding for trans youth healthcare, just to give a couple of examples from the last weeks alone.

The Johns Hopkins Gender Clinic, established in 1966, was among the first to pioneer gender-affirming care. However, by the late seventies, transphobic rhetoric was building in the mainstream, echoing sentiments similar to the spurious moral panics of today. While the Affordable Care Act of 2010 broadened protections for gender-affirming care, these are now threatened by Trump’s January Executive Order.

What next?

Things can feel terrifying, but if you’re feeling angry the way we are, embrace it. Anger can be a catalyst, for seeking information and sharing it, for making change. This Policy Watch article breaks down the troubling and rapidly-changing developments in US trans healthcare. The National Abortion Hotline has a host of resources for those in need, including the largest toll-free advice and information abortion hotline in North America. Coordinated networks across the US organize the delivery of abortion pills to those unable to access abortion by other means; in the two months following the revoking of Roe v. Wade, there were 10,000 fewer abortions in the US.

Though it may have been long-demonised, femme rage is going nowhere in a global landscape shaped by the encroachment of the far-right. In solidarity and in community, rage is more important and more powerful than ever.