Teenage girl revenge: An interview with sculptor Flora Wilds

Photographs courtesy of Flora Wilds

Renowned for her used bikini sculptures, the artist discusses how to make art while in love, 2000s aesthetics, and the mall. Meet your future favourite sculptor.

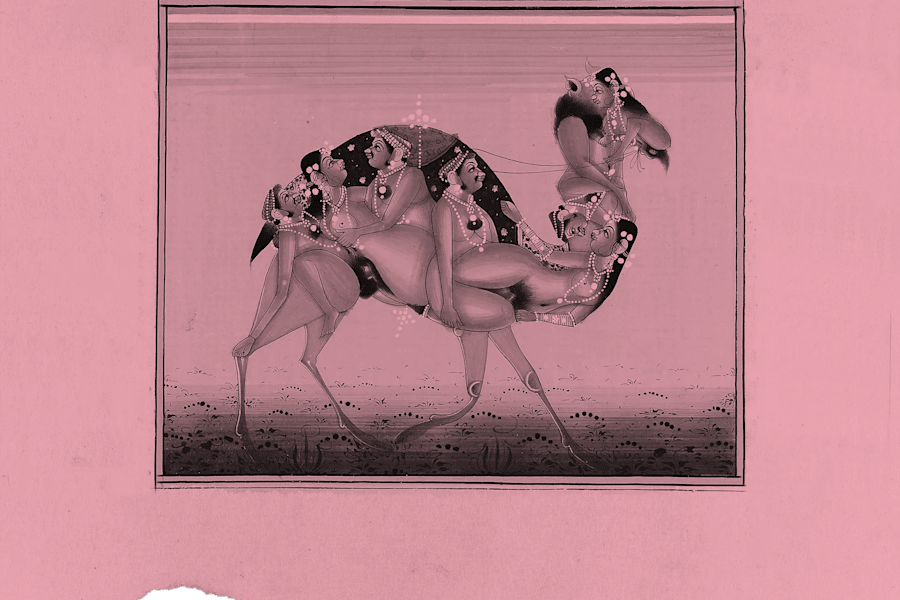

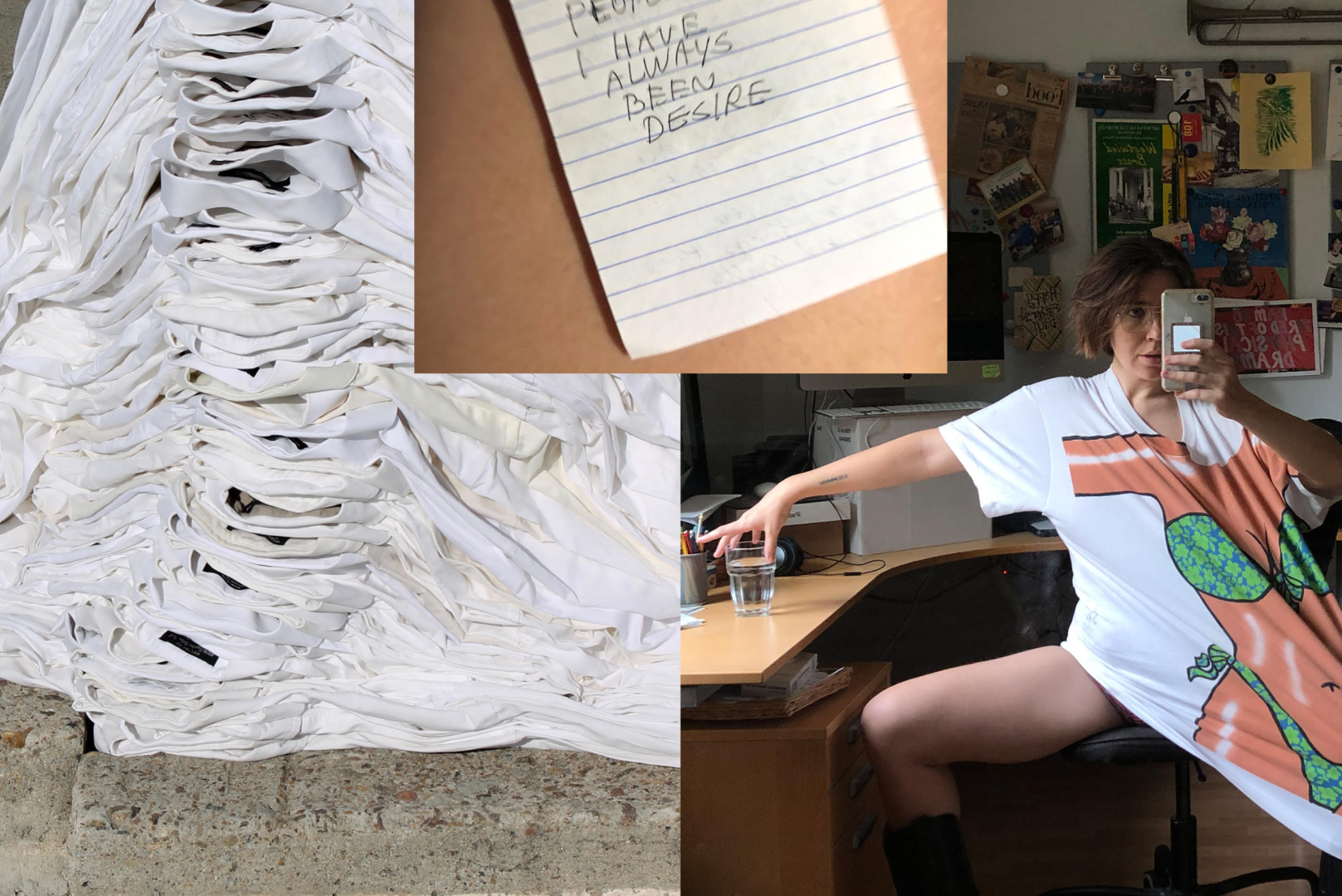

Known by her cult-following for her used bikini sculptures, Flora Wilds’s fans include Miranda July, drag queen Pattie Gonia, and artist Syrus Marcus Ware. Wilds’s mission to queer the sculpture canon means working only with found materials and repurposing supposedly “feminine” commodities—purses, swimsuits, quilts. Half polemic, half celebration of 2000s girlhood, her works feature 14-foot-tall stretched bikini statues, repurposed Britney Spears merch, and giant tapestries woven from “undesirable” offcuts.

In Flora’s studio, her most recent sculpture from a series called swim-ssssstretch looms over us like an angry, teenage demi-god. Reclaiming denigrated items from the 2000s, Wilds’s work is potent, fleshy, with a strong backbone of “teenage girl revenge” at its core. Flora spoke to Feeld about cheerleading, malls, NYC vs. SoCal, and the tensions between being an artist and being in love.

Flora Wilds

'false neutrals, fake naturals' by Flora Wilds

'bikini quilt (in the round)' by Flora Wilds. Image credit: Tori Hilshey.

You recently moved back to SoCal from New York. What did New York give you and why did you decide to leave?

New York gave me my palate—it helped me cultivate my eye and what materials I was interested in. And it put me in direct communion with so many incredible artists. It’s a place where art is being done at the highest level with the most intense people. But in New York, you don’t have the space to work big. My work is maximalist so I was always pushing against the edges of a container and at some point that started to feel more frustrating than generative. There’s literally just more room in L.A., I’m able to dig into work at a pace that’s satisfying to me. Figuring out bigger iterations of sculptural works, discovering new modes—it feels really expansive. I had many rich years of soaking up my New York experiences and now I get to come to L.A. and work them all out in a bigger space with a better quality of life. At the end of the day, I'm a SoCal bitch and I like to feel healthy. In New York, I was sick all the time, stressed all the time, broke all the time.

Your work is so much about desire, embodiment, yearning. How have you navigated the reality of being an artist and maintaining relationships?Last year, I texted my whole contacts list—anyone I know who makes art—and asked them, how do you make art and also be in love? I got a lot of answers from cis men who seemed to have no problem with it. But for me, there was this level of accommodation that as an artist, and a woman, was expected from me. Partners being like, “Oh, you're not working a nine to five, you’re just going to the studio, so can you fit X, Y, Z into your day while I'm working?” After enough times you say yes to that because you are broke and wanna make up for that with the time you have. But I know now my practice needs a lot of protection. I haven’t been partnered since last year, and I'm really seeing a difference in terms of how much I'm able to give to my work.

Do you feel like it's different in queer relationships?I kind of think that no matter who I'm with—man, woman, whoever—I'm always anxious that they're starting to take up more room in my brain than my ideas. I'm super attuned to that now. I'm feeling very greedy with my relationship to self and practice.

It’s so hard to balance having interconnected, mutually caring relationships but also insist on your own space and work.Exactly, because I don’t ever want to cut myself off from the vibrant, contentious space of love. It’s where I do all my learning, it reminds me consistently of all the revelations that I've come to throughout my life.

You’re known for working with found materials—2000s bikinis, cement blocks, old tapestries. Why is that?To me, the world is already so full. It feels much more interesting to put a new gaze on mundane objects. It requires you to be in tune with their origins and production. A bikini top made by someone in a sweatshop overseas is a handmade object. Plus, I'm just obsessive about wanting to use up every last bit of something.

Your recent sculptures seem to have such 2000s aesthetics—the golden era of the mall, lip gloss, Britney. What were your influences as a teenager?I was an athlete: a gymnast and then a cheerleader. A term I use a lot in my work is “physical drama” which comes from cheerleading as a practice. It was a stronghold in the mid 2000s in Southern California, intensely competitive, this very loud presence. Some of that loudness is definitely there in my work—all-girls, Catholic school drama.

Yes, cheerleading is so strength-based, you’re throwing yourself around all over the place. And your work is so embodied in that way—this strong, intimidating girl-gang feeling, and insistence on pleasure. How does that all fit in with the parts of your work focused on malls and mall culture?Malls are so fascinating—they’re where you go to first learn to desire things. This constant searching for the next object that you're desiring. I remember being at Macy's and yearning for these purses that my future adult self might have one day. I could never dream of being a Chanel girl at the mall. But I could dream of saving up all of my allowance for like, a year, and buying a Coach purse to tote around high school, which is what I did. In that way, desire is stoked—this endless loop.

And the mall is a social event. It’s where everyone went to meet their crush.Yes! Getting dressed up to go to the mall. You're strutting around, wearing three tank tops and a pushup bra, hoping you might run into someone. And even the structure of malls themselves have influenced me. The mall that I grew up with was deconstructed during the pandemic and I would go take photos of all the “mall guts.” The piles of rubble and concrete. We don't let stuff get old in America—we don’t have preservation as a priority, especially on the West Coast. So I started stealing concrete blocks from these building sites.

In swim-ssssstretch it feels like you’re taking these macho concrete blocks and repurposing them into a completely new, fleshy context.In grad school I developed an aversion to minimalism—artists like Richard Serra using cement and giant concrete structures to intimidate and impose a sort of stark threat to the body. It felt like a big aesthetic and political contrast to my maximalist, feminist work. And the act of collecting those concrete blocks is so fun because then I have to be out in the world, in a city, searching.

A big critique of contemporary art is that it is born and dies in academia. But it seems you are very much a working artist out in the world—gathering materials and ideas out on the streets.

That's what I prefer! Creating in the vacuum of my head in the studio does not feel good to me. Everything I learned from my practice, I learned from taking photos on the streets of New York, seeing relationships between objects. I spent my first year living in New York barely making work, but just being in New York. That was much more generative than being in a studio. That's the problem with art school—it's trying to help students attune their aesthetics without letting them out to glean and reflect and figure out what their stakes are. And another part is not giving myself other options—my approach to getting into the art world has been sort of just how I can. My mom is my main install person because I can’t pay anyone else. My dad doesn't own a gallery. I didn't go to Yale. There’s like this delusion within me, that also has been one of my greatest strengths.

Totally agree, yes. Delusion but also—endurance. Just like keeping at it. Being able to withstand a lot of rejection and no’s. And it’s good too if you can keep a crumb of humor around.

You run “Astrology for Artists”—astrology readings for makers. How did that come about?I was working for a sculptor and would bring up astrology from time to time. And he started asking me more intentional questions about it and it just became this integrated thing through the process of working for him. Eventually, I started offering readings on Instagram, because that's my largest platform and it’s where I ended up generating most of my income from. I'm not super interested in answering people's questions, like, should I break up with my boyfriend? It’s more peer-to-peer, talking through their artistic process, having these really active, intentional, and interesting conversations that get to the core of art-making, using their charts.

What are you working on right now?I have recently been working on some new swim-ssssstretch work—deconstructing and collaging tankinis and one pieces, working toward creating 10 or 15 of those—a whole squad of them. It takes a while because with every object, I have to think about which form it wants to take. How much deconstruction is necessary? How much do I want the viewer to be able to immediately recognize what it is?