Text Me When You’re Done: Degrassi: The Next Generation

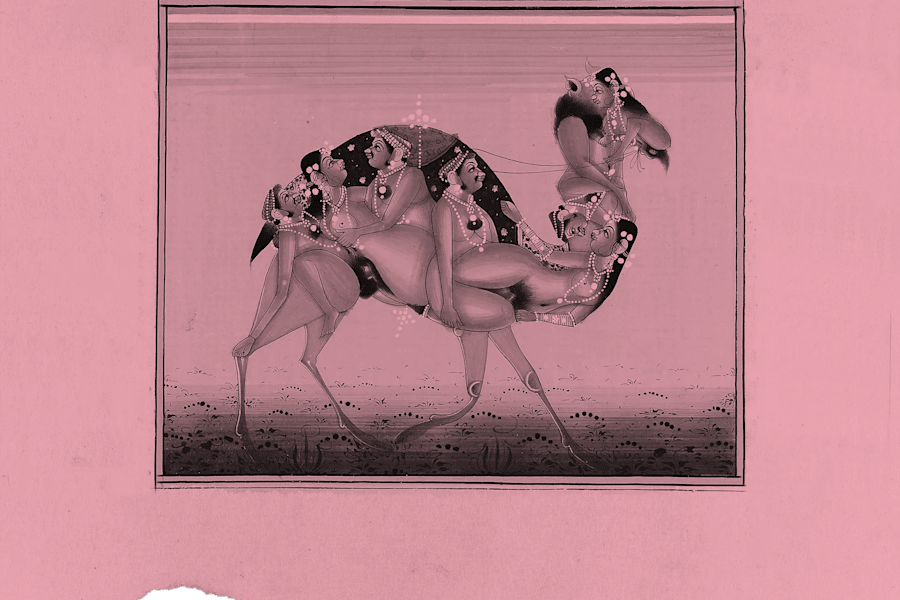

Cast of Degrassi: Next Generation celebrate their 100th Episode (Photo by George Pimentel/WireImage)

Lola Kolade on the nostalgic love lessons of a classic Canadian teen drama.

When I was in middle school, my family moved from New York to a frightening Stepford suburb in New England, a Waspy oasis on Connecticut’s Gold Coast. The residents were fiscally conservative but allegedly socially liberal, the type to let you know they'd have voted for Obama a third time if they could have. When I started school, it was about three or four months before my classmates learned my name. For the early part of that school year they called me Diane, the name of another Black girl in my year—only her family had moved away the year mine arrived. It was destabilizing in the way that only an adolescent move can be, which meant that it felt truly catastrophic, made even more rending by the fact that I could see all the fun my old friends were having without me in flash-heavy Facebook albums showing pictures of them doing nothing in particular.

But loneliness and micro (macro?) aggressions aside, there was a gleaming bright spot cutting through the bleak suburban haze of layered Abercrombie polos and fold-over waist yoga pants: my family finally got cable. After a childhood reared on Nollywood classics like Osuofia in London and Sharon Stone in Abuja, I finally had access to an expanded cable pack that included MTV, the then-nascent . (RIP UPN), and most importantly, The N, Nickelodeon’s now-defunct programming block on its sister channel, Noggin. At the center of The N’s slate was Degrassi: The Next Generation, the early-aughts iteration of Degrassi Junior High, the perennial Canadian teen drama that covered everything from bullying (evergreen), to teen pregnancy (multiple), to outbreaks of gonorrhea, the infected handily marked with bracelets awarded by the school’s chief dirtbag for giving head.

Naturally, I quickly became obsessed. I watched the show with the kind of rapturous focus my nerdy ass typically reserved for my homework. A staple of Canadian public broadcast since 1979, Degrassi: The Next Generation’s low budget melodrama enmeshed itself in the soft gray matter of my still-developing brain, much like the Heelys I always wanted but never got, or the theme songs of several TV shows that didn’t make it past the first season. As the years passed, the show only became more legendary. The ensemble cast of that era birthed many stars who graduated to glossier American teen soaps, spawned parodies on Kroll Show and Saturday Night Live, and there was also this guy named Aubrey Graham, who I’m told raps now or something.

Long before Gossip Girl’s masterfully deployed outrage campaigns, Degrassi promos boasted “it goes there,” highlighting the range of teen issues the show dared to explore. Instead of being terrified by the gamut of after school special-style problems that rained down on the students of Degrassi like biblical plagues, I was invigorated and intrigued. This, I felt, eyes glued to the screen, was real life. Sitting at home while I adjusted to the move, my childhood love of reading developed into an obsessive TV-watching habit that’s drawn a direct line to my career as a TV writer, critic, and pop culture-obsessed digital content creator.

Degrassi has always been an unpretentious entry into the teen drama genre, eschewing the obviously-written-by-30-year-olds witty banter of Dawson’s Creek and the designer-dotted wardrobes of The O.C.. It had its fair share of heightened made-for-TV moments, but for the most part it was grounded and spoke to its teen audience with authenticity and respect, handling controversial topics with a steady hand. It really did go there. Take, for example, the 2004 episode where fourteen-year-old Manny Santos, the iconic bad bitch of sparkly blue thong fame, gets an abortion—which didn’t air on American television until two years later. Even now, the 2002 episode where the Black Muslim character Hazel Aden hides her Somali heritage by pretending to be Jamaican—a fairly common occurrence for first generation African kids in the late ‘90s and early ‘00s—is an instance of hyperspecific representation I still haven’t seen replicated elsewhere.

There is something unique about the media we love as teens, when we’re still pink in the middle, not quite done cooking yet. Our tastes are malleable, susceptible to the interests of our siblings and friends and whatever the dominant cultural discourse is—even if we’re being deliberate about self-styling as a rebel who goes against the grain. It’s a time of an abundance of firsts that are simultaneously seismic and not that deep. The emotional intensity of the period makes the attachments we form to media especially acute, the same way a breakup can ruin a favorite song because it viscerally reminds you of the ex who used to play it on repeat. As Josh Schwartz, the creator of teen TV juggernauts The O.C. and Gossip Girl, once said, “if you are a show that means something to somebody when they're a teenager, they're going to love that show forever.”

This is why it’s so easy for me to work my enduring love for the show into conversation, and why a handful of thirty-something guys I’ve dated spread across various metropoles understand the significance of the legendary line, “new year, new look, new Paige”—how else would I announce that I’m embarking on a new era and they’re lucky enough to be included? It’s why I revisited some choice episodes earlier this year, reaching for the gauzy comfort of nostalgia to coax me through another big move. Even now, the show’s theme lends me a lesson on how to approach life’s challenges: whatever it takes, I know I can make it through.