Text Me When You’re Done: Tampopo

Tampopo, 1985. Director:Juzo Itami. Photography of Tsutomu Yamazaki, Nobuko Miyamoto by Itami Productions.

The ideal date movie exists, and it has a scene where two people pass an egg yolk back and forth into each other’s mouths. With the potential for pleasure hanging in the air, Tampopo is the perfect prelude.

As an admitted movie snob, I’ve sometimes made the rookie mistake of trying to impress a new crush with an overly cerebral film, effectively tanking the vibe before it has a chance to grow. Tarkovsky’s The Sacrifice was one such error—I brought a date to a screening, without considering what it would be like to sit through it with someone I barely knew and was hoping to make out with. I still love Tarkovsky, but The Sacrifice’s long monologues about impending nuclear war, its themes of martyrdom and destruction, and that superb but terrifying final shot of a burning house on an empty plain, do not exactly inspire flirty banter or suggestive arm-brushing. I spent most of the film in an anxious sweat, convinced that my date would give up and walk out on me. The relationship ended up lasting a couple months, but I can’t help but blame my favorite Russian director for its eventual rather bleak collapse.

In recent years, having grown older and a little wiser, I’ve embraced lighter viewing for early dates. Juzo Itami’s Tampopo has become my go-to choice: the only “ramen Western” in existence, it’s an energetic, often hilarious movie, filled with absurdity and charm, and brimming over with delicious noodles. When I’ve shown it to new friends and dates, it has been a resounding success. “Ramen Western” is exactly what it sounds like: a Japanese film about ramen, told using tropes from Hollywood Westerns. There are ramen-shop brawls, stand-offs with rival noodle-purveyors, a rugged cowboy figure, a steadfast saloon (ramen-shop) owner, and the classic tension between settling down and the call of the open road.

The film’s main storyline begins when Goro, a stalwart trucker who dresses like a cowboy, rolls up to a roadside ramen shop with his trusty sidekick Gun. The shop is run by the good-natured Tampopo, a hardworking widow who took over her husband’s noodle business after he died, to middling success. It turns out that Goro and Gun are ramen connoisseurs, and soon they are assembling a crack team to help turn Tampopo’s ramen shop into the best in the city. Goro adopts the guise of a tough-but-fair (and sexy) sports coach, putting Tampopo through a ramen-training regimen, complete with jogging and timed soup-ladling drills. The two of them soon develop an understated romance. Their mutual attraction is sweet and a little sad (out on a date, they tell each other about the loss of their previous partners), but what really energizes their relationship is a mutual obsession with achieving the ultimate ramen recipe. This erotic pursuit involves consulting the neighborhood crew of gourmet beggars who salvage epicurean feasts from the dumpsters of the wealthy; spying on rival ramen shops for broth and noodle recipes; and developing a heightened love and respect for each and every ramen ingredient, as well as a deep attention to customer reactions. If the diners sip their broth too early, it’s not hot enough. If they slurp up every last drop, burrowing their faces into their bowls, the ramen was a success.

In the film, the sexual and the sensual intermingle: an appetite for orgasm is inextricable from an appetite for the perfect meal. In one scene, Tampopo is hustled into a dark back room by one of her ramen-trainers: “What are you doing?” she exclaims, resisting slightly. The scene is set up as if something smutty is about to take place, but when she finally looks through a peep hole, as directed by her guide, instead of spying on something titillating, she finds herself watching a competing ramen shop owner preparing his secret broth. She thrills at this—the pleasure of stealing a forbidden look at culinary secrets is equal to that of a naughty peepshow.

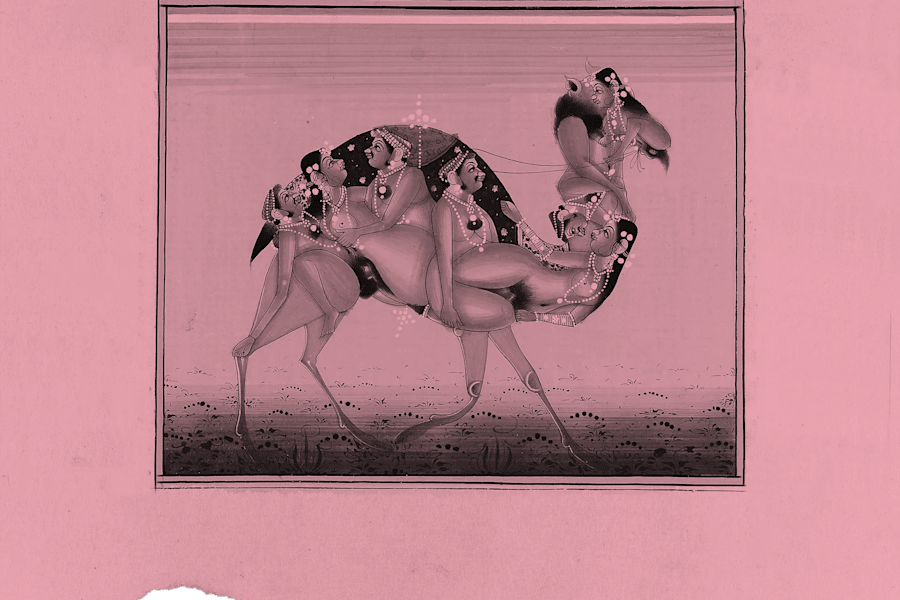

The story of Goro and Tampopo is interspersed with absurd food-themed vignettes, some laugh-out-loud hilarious, some deliciously horny. An elegant Japanese woman teaches a group of eager young ladies how to properly eat spaghetti in the western way, without impolite mouth sounds; but the young ladies glimpse a white man across the restaurant, slurping his spaghetti loudly—as one, they all begin to slurp and gobble with abandon. A well-dressed older woman sneaks around a grocery store, gleefully poking her fingers into various pastries, fruits, and dairy products, leaving dirty dimples in the goods; she is chased by the beleaguered shop owner in a memorable cat-and-mouse sequence. In a hotel room, a dapper gangster and his lover, both dressed in white, cavort with a smorgasbord of foods—he salts her nipples and dribbles them with lemon juice before sucking them, then places a bowl of crayfish and sauce upside down over her stomach so that the crayfish dance in her bellybutton. Trembling, they pass a raw egg yolk back and forth between their open mouths, until the woman loses control and breaks the yolk with a moan, letting it spill out over her chin.

Tampopo has everything you could want in a film: romance, brawling, sensual pleasure, discipline, camaraderie, comedy, noodles—and death. Despite its distance from Russian drama, Tampopo is, in its own zany way, preoccupied by mortality. In one of the vignettes, a salaryman runs home through the city evening at breakneck speed, to a small apartment where his wife is on death’s door. He begs her not to die, instructs her to get up and make dinner, which she does, zombie-like. “It’s really good!” he assures her as he and their kids eat it up. She smiles, before collapsing again. “Eat, eat,” he shouts at the kids as she is pronounced dead by a doctor. “It’s the last meal your mother cooked!” Near the end of the film, the gangster in the white suit is shot in the street—bleeding out dramatically in the rain, as he is cradled by his lover. He tells her about hunting wild boar in the wintertime. The boars gorge themselves on yams to survive the cold; after killing them, the hunters make sausages from their yam-filled intestines. “Sounds good, huh?” gasps the man in white. “Yes, perfect with soy sauce and wasabi,” she sobs back. “I wanted so much to eat them with you,” he says, before falling back, lifeless. Without the lingering shadow of death, Tampopo would be too silly a film, perhaps, its ebullience and charm collapsing into mere cuteness. I like my pleasures with a threat of oblivion on the side.

Watching Tampopo always makes me mildly melancholic, a little bit horny, and undeniably hungry. I love it because it leaves me with an appetite, and I want to date people who, like me, have a craving for excess and sensory delight. After all, as Goro admonishes Tampopo at the start of her training: “Lukewarm ramen isn’t ramen!” Fortunately, my partner of several years, who watched Tampopo for the first time with me early in our relationship, emphatically agrees. It wasn’t until dating them that I realized how important a shared pursuit of pleasure is for me—it doesn’t have to be elaborate or expensive, as Tampopo shows us, but you must be willing to let yourself be entirely overcome. You must be willing to take risks, to court the intoxication of the senses though it may lead you to the brink of death, or at least past the bounds of logic and decency. When I ask you to watch this movie, I’m really asking: With the raw egg yolk running down your chin; with your fingers poking ecstatically into swollen grocery store peaches; with the crayfish dancing on your naked belly; with an awareness of time running out, will you plunge headlong into pleasure with me?